Paying compensation to the descendants of slaves would not just right a historic wrong, it would transform the US economy for the better.

By Aaron White, openDemocracy —

When I was a child, I used to visit my Viennese grandmother in the rent-controlled apartment on New York’s Upper West Side that she had been living in for nearly 50 years. I remember the intoxicating smells of sizzling schnitzel and her warm greeting in a thick Austrian accent.

My grandmother escaped the Nazi takeover of Vienna in 1938 underneath a sack of potatoes in the back of a truck. She managed to reach the UK, and later New York, where she joined a community of Austrian and German Jewish refugees.

She never taught her children German and refused to ever set foot on European soil again. She was incapable of watching films on the Holocaust, and never spoke about it with me.

When I was ten years old she passed away. Among my memories, a few stand out. I remember seeing monthly reparations checks on her dining room table for $150 – issued by Germany and disbursed through an Austrian bank. Since 1952, the German government has paid out more than $80bn to victims of the Holocaust.

This money was just a fraction of what had been stolen from her family: apartments, furniture, jewelry, paintings and lives. It wasn’t enough to alter her modest livelihood, but it was a constant acknowledgment that she was owed.

Demands on the streets

Over the past year I’ve spent time talking to many Black Lives Matter activists across the US, asking them what they’re demanding from the new political leadership in Washington. The answer is strikingly consistent: reparations.

One of these activists is Antonio Brown, a 35-year-old Black man who has lived in Louisville, Kentucky for nearly his entire life.

Antonio has been campaigning for justice for Breonna Taylor, the 26-year-old hospital worker who was killed by Louisville police in March 2020. Like many activists I’ve spoken with, he cites historic examples of reparations that have been paid to other dispossessed communities in the US.

“It’s crazy people these days still don’t believe that we should get reparations. The Indians got them, the Asians got them, but we can’t,” Antonio told me.

In 1946, Congress passed the Indian Claims Commission which disbursed $1.3bn to Native Americans. In 1987, the US government paid $20,000 to each Japanese American who was interned during the Second World War.

President Reagan signing a reparations bill in 1987 for Japanese-Americans interned during World War Two | Alamy Stock Photo

Over the past year, the US has witnessed the rise of the largest racial justice movement in its history. Following the recent police killings of Daunte Wright, Ma’Khia Bryant, Adam Toledo, the Black Lives Matter movement doesn’t appear to be fading anytime soon.

Although many institutions across civil society have publicly endorsed Black Lives Matter, and the demands for police accountability remain broadly popular, the idea of reparations is met with discomfort amongst the more liberal end of the elite – and a significant majority of the US population.

But in the wake of last summer’s protests and a pandemic that has disproportionately affected non-white communities, support for reparations is gaining momentum.

In a 2002 CNN poll, only 6% of white respondents were in favor of reparations. Yet between 2019 and 2020, white support increased from 23% to 39%.

For young Americans, the policy is even more popular. Polling last month by UMass Amherst suggested that nearly 60% of young Americans aged 18-29 supported reparations.

This increasing support has also entered the political arena. During last year’s Democratic presidential primary, Senators Elizabeth Warren, Cory Booker and Kamala Harris endorsed varying forms of reparations policy – while spiritual leader Marianne Williamson campaigned on a $500bn reparations program.

HR 40, a bill that would establish a commission to study reparations, was reintroduced in Congress by Texas Representative Sheila Jackson Lee with 184 co-sponsors. The bill was approved in committee, and might advance to the floor for a full vote this legislative cycle.

Across the US, local governments from Evanston, Illinois to private institutions such as Georgetown University, have enacted reparations policies. Even Barack Obama, who opposed reparations while in office, recently said they could be “justified”.

At the same time, there continues to be a dearth of serious engagement with the question of what reparations would mean in practice.

Who should pay for reparations? What form should they take? How much would it cost? Who would be eligible? And what would the socio-economic and political implications be?

I’ve been asking people this question for the last month – from Black activists to prominent economists – and it turns out the answer is reasonably simple.

‘What happened to our 40 acres and a mule, fool?’

In 1865, in the wake of the Civil War, General Sherman announced Special Field Order Number 15, which declared that former slaves would be allocated 40 acres and mule in former Confederate land, along 400,000 acres of the south west stretching from South Carolina to northern Florida.

The order read: “The islands from Charleston south, the abandoned rice fields along the rivers for thirty miles back from the sea, and the country bordering the St. John’s river, Florida, are reserved and set apart for the settlement of negroes now made free by the acts of war and the proclamation of the President of the United States.”

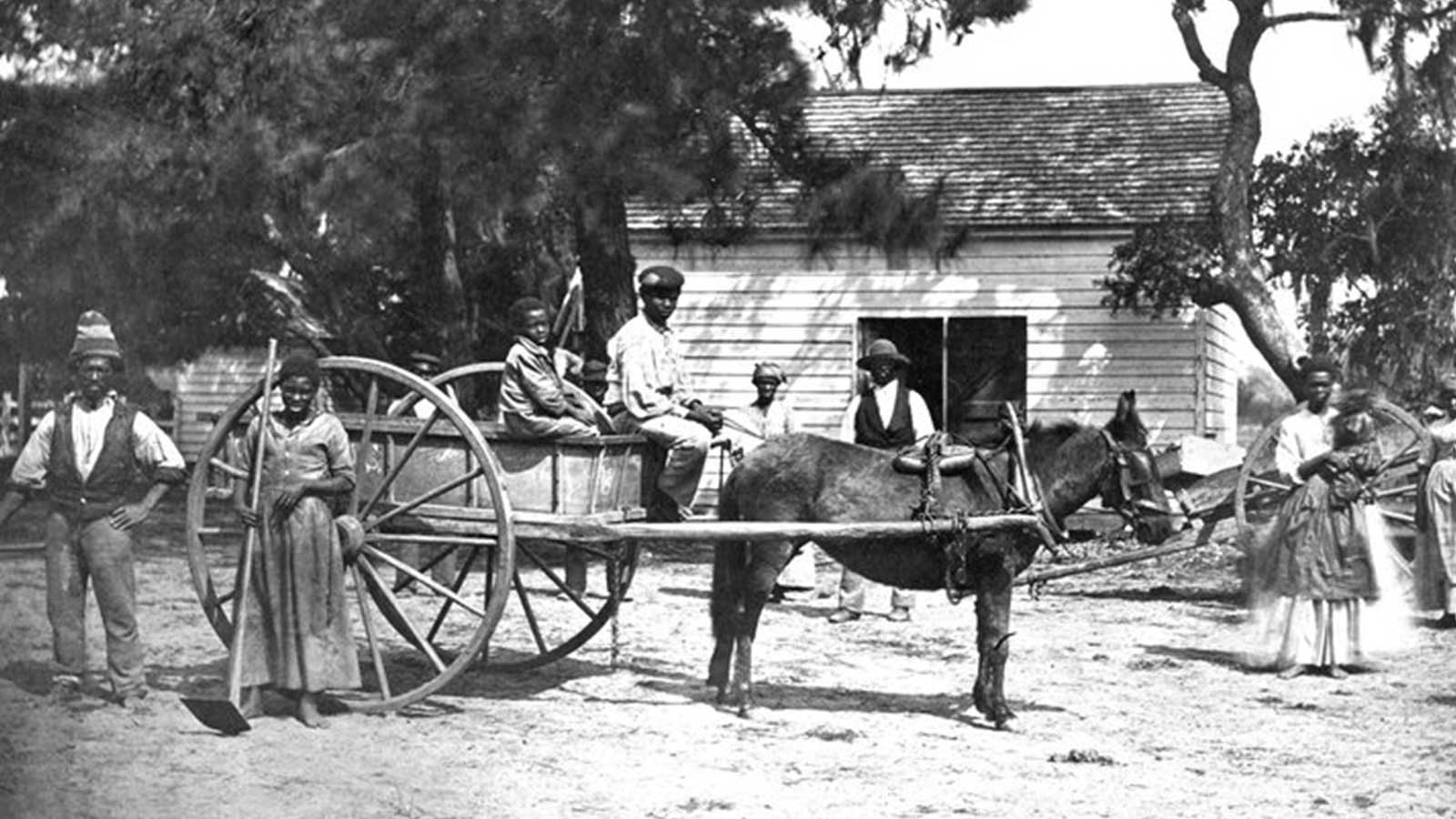

A Black Union soldier with his wife and two daughters taken in 1863 | Alamy Stock Photo

Many accounts suggest that this promise resulted from a discussion between General Sherman and 20 leaders of the Black community in Savannah, Georgia. Garrison Frazier, a former slave and Baptist minister, told Sherman that “the way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land, and turn it and till it by our own labor.”

Later that year, however, Lincoln was assassinated. Andrew Johnson, his successor, annulled the order to appease the southern states.

By contrast, just a few years earlier, many white families were granted acres of land by the federal government following the passage of the 1862 Homestead Act. As Kirsten Mullen, the co-author of ‘From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the 21st Century’ explained to me:

“The Homestead Act was right there in time with the failed promise of 40-acre land grants to the newly emancipated people. So you have white Americans, including recent immigrants receiving 160-acre land grants, and Black people being promised 40 acres but receiving zero.”

Following the brief period of Reconstruction – whereby many former slaves achieved significant political and economic gains – racial exploitation took on a new form.

In order to survive, former slaves had to sell their labor back to the racist society which had enslaved them. They went from being someone’s property to living in desperate poverty. Following decades of terror, discrimination and destitution, large numbers of Black families migrated to Northern cities, in a period that became known as the Great Migration.

Between 1915 and 1930, over six million Black people relocated from the South to the North. In cities such as Detroit, New York and Philadelphia – the Black population more than tripled.

After the Great Depression, and the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the New Deal was enacted. Yet Black people were excluded from these regeneration policies through measures such as redlining and racist covenants, whereby Black people were denied government-backed mortgages or the ability to purchase homes in majority-white neighborhoods.

In 1947 Mississippi, only two of 3,200 government-backed mortgages in 13 cities went to Black borrowers.

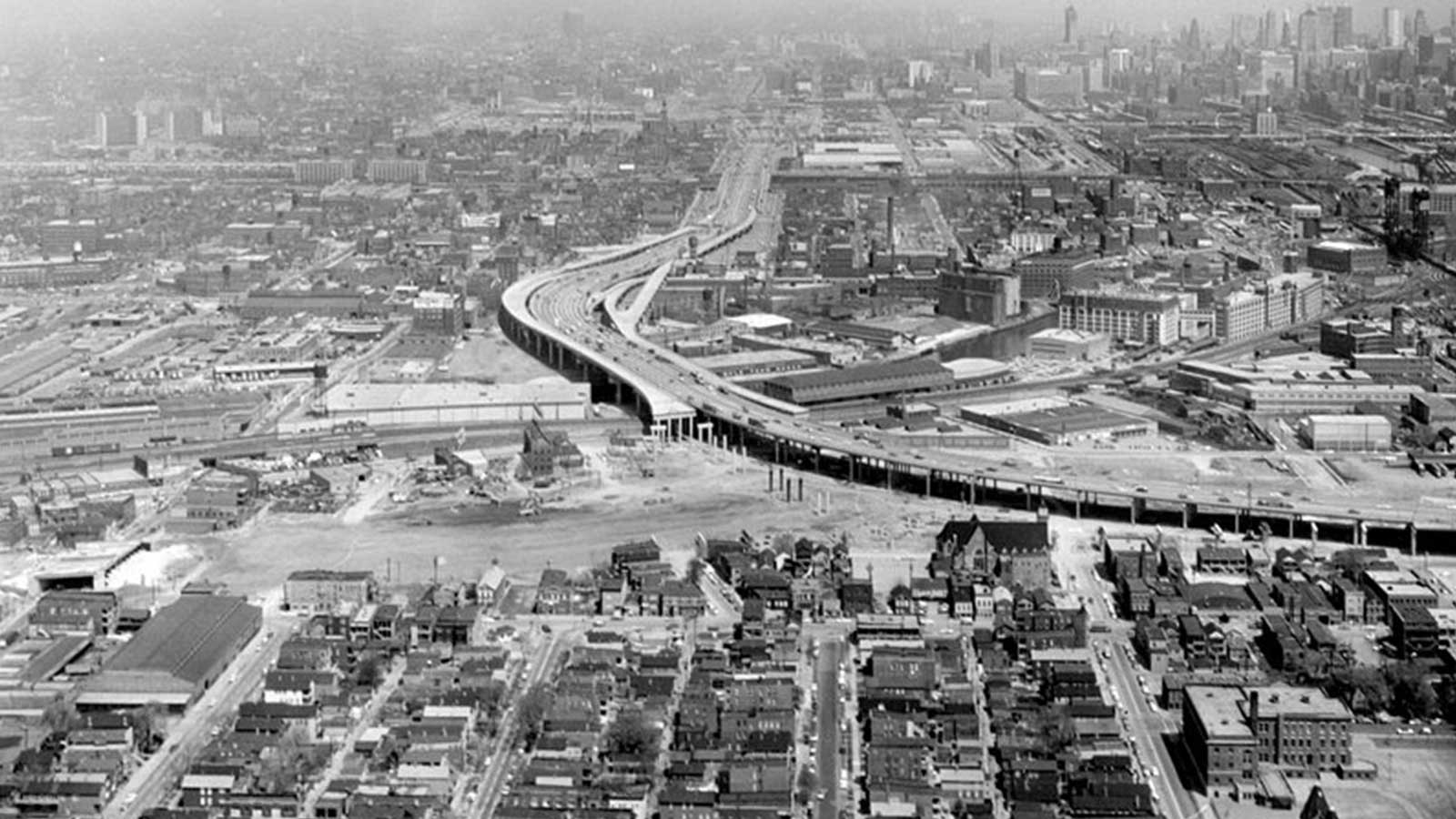

Black people were also disproportionately affected by post-war policies such as the Federal Highways Act of 1944, which devastated Black urban residential communities.

Highway construction in Chicago in the early 1960s | Alamy Stock Photo

Even after the passing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, racialized social and economic inequality remained pervasive, enforced through predatory debts and the slashing of social welfare programs.

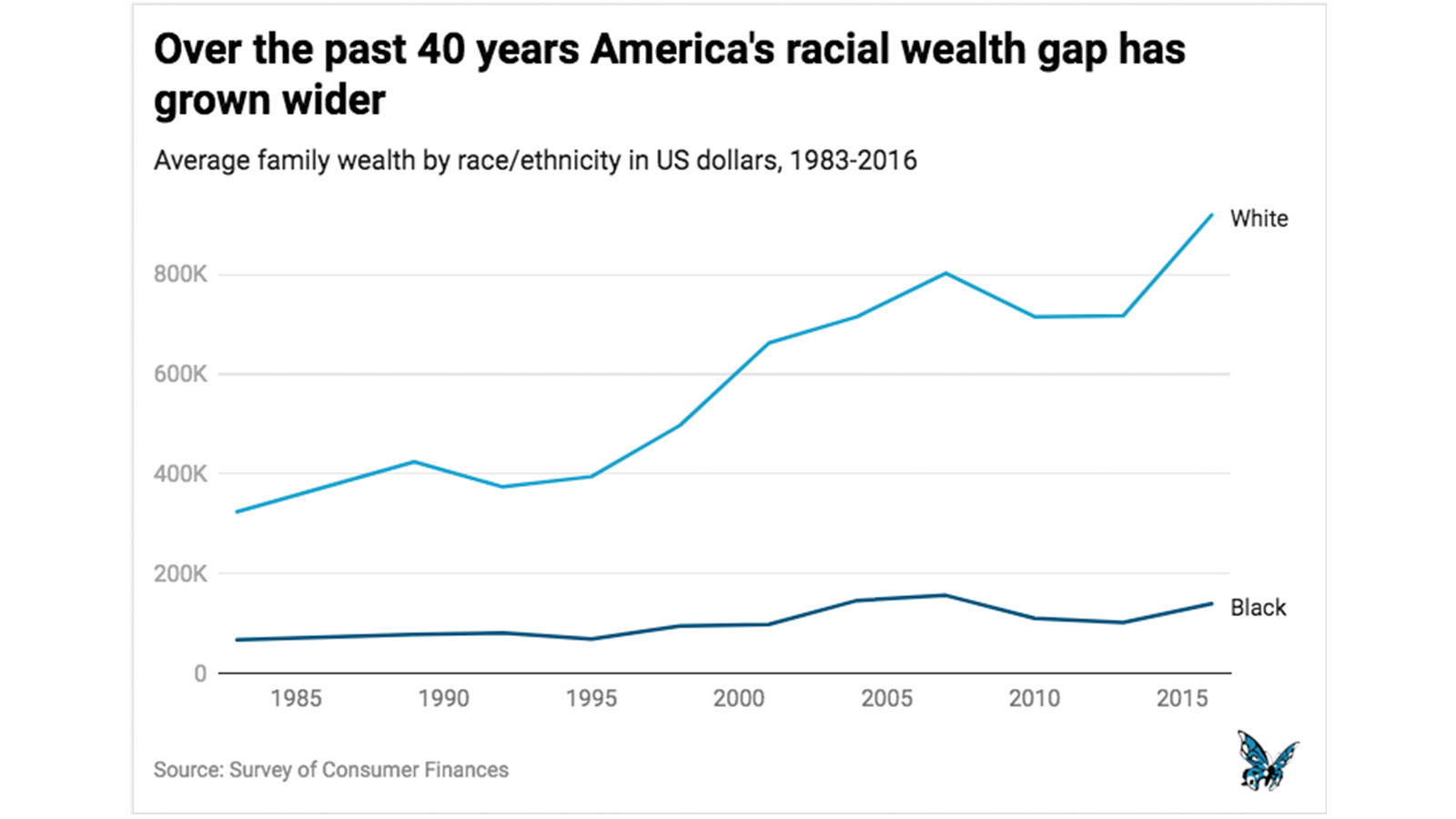

In an analysis of the racial wealth gap over the past 70 years, economists Moritz Kuhn, Moritz Schularick and Ulrike I. Steins reveal that there has been no progress in “reducing income and wealth inequalities between Black and white households over the past 70 years.”

According to the Urban Institute, between 1983 and 2016 the median Black family’s wealth grew from $13,324 to $17,409. Meanwhile, over that same period a typical white family’s wealth grew from $105,369 to $171,000.

Instead, mass incarceration has skyrocketed by 700% since 1970, with Black people imprisoned at five times the rates of white people. And Black people who represent 13% of the general population account for 39% of people experiencing homelessness.

Instead, mass incarceration has skyrocketed by 700% since 1970, with Black people imprisoned at five times the rates of white people. And Black people who represent 13% of the general population account for 39% of people experiencing homelessness.

While many white communities may have forgotten Sherman’s promise, Black activists and artists haven’t. From the Commodores’ 1975 song ‘Gimme My Mule’ to 2Pac’s 1999 hit ‘Letter to a President’, and Spike Lee’s production company, ‘40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks’, the pledge has re-emerged in Black popular culture.

Since the 1960s there has been a revitalization of the demand for reparations. The National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (N’COBRA) was founded in 1987 by a consortium of Black leaders; the Movement for Black Lives launched in 2015 following the killings of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Tamir Rice endorses reparations; and the #ADOS (American Descendants of Slaves) online movement has gained momentum in recent years amongst activists and young elected politicians advocating for reparations.

These calls are being echoed on the streets across America. As Carmen Jones, a 24-year-old homeless Black Lives Matter activist who has travelled the country protesting against the police killings of Black people, told me: “Every system has done us bad: healthcare, housing, education, policing, the law.”

“I need a check, my kids need a check. We need checks going back 600 years – y’all can’t pay the ancestors, so you have to pay the descendants.”

Reparations in practice

To find out what reparations might mean in practice, I spoke to William Darity, an economist at Duke University, and his wife Kirsten Mullen, a folklorist, who are co-authors of the book ‘Reparations for Black Americans in the 21st Century’. I asked them what a comprehensive reparations agenda in the US might look like, starting with the question of who should pay for them.

In contrast to recent reparations delivered by local governments and private institutions, Darity and Mullen assert that the invoice for reparations must go to the federal government, which bears responsibility “for sanctioning, maintaining and enabling slavery, legal segregation, and continued racial inequality”.

From the failure to grant 40 acres and a mule while many white families received Homestead grants, to the exclusion of Black people from the New Deal and GI bill, Darity explained that “it’s federal policy that has created the racial wealth difference that we observe in the US, and so we argue that it’s the federal government that has to close the gap.”

On what scale should reparations be paid, and how much would they cost?

Darity and Mullen consider the racial wealth gap to be the “most robust indicator of the cumulative economic effects of white supremacy in the US.” As a result, they say that reparations should aim to eliminate the racial wealth gap between Black and white families in the US.

According to the Survey of Consumer Finances, the average household wealth gap is around $840,000. Eliminating this gap, and bringing the Black share of wealth into conformity with the Black descendants of US slavery share of the population (13%) would cost around $11 trillion.

What forms should reparations take? For Darity and Mullen, reparations can take several forms including: direct payouts allocated over 10 years, public trust funds that give out grants for asset building projects (such as homeownership, education, self employment, purchase of financial assets), or funds to assist in developing endowments of historically Black colleges and universities.

Direct payments are a critical part of the proposal. As Mullen put it, “we absolutely think that it’s important for both symbolic and substantive reasons for a significant amount of funds to be distributed to Black American descendants of slaves as direct payments or cash payments.”

Mullen emphasized that these payments can be made in less liquid forms, to avoid runaway inflation, and can stretch out over a decade. “For individuals who have not yet reached the age of maturity, those funds could be put into savings accounts, which would slow down these expenditures to some extent”, she said.

Who should be eligible for reparations? For Darity and Mullen, there are two main criteria. The first is that recipients must have at least one ancestor who was enslaved in the US. The second is that recipients must be able to prove that they self identified as ‘Black,’ ‘negro’, ‘Afro-American,’ or ‘African-American’ at least twelve years before the enactment of the reparations program.

For many, an obvious question is: ‘can we really afford this?’ As proponents of Modern Monetary Theory, Darity and Mullen believe that the Federal Reserve can easily manage an annual outlay of $1 to $1.5 trillion if directed by Congress without raising taxes.

I asked Darity whether a reparations agenda should be financed not only by public deficit spending, but also through higher taxation rates on the wealthy. He sharply disagreed.

“The question of financing the project is not one that has to be constrained by tax revenue of any type. The combination of the funding for the CARES Acts, for the American Rescue Plan, the response to the Great Recession: all were instances in which the federal government generated very large sums of money overnight, without relying upon additional taxation,” he said.

The only constraint, according to Darity, is inflation. He emphasizes that the inflation risk will be dependent on the extent to which the new resources will stimulate more employment and production within the economy.

“We’re talking about a substantial change in Black American descendants of US slavery’s economic well-being and opportunity,” Mullen said. “An opportunity to purchase a higher amenity home, to send your children to higher quality schools, an opportunity to invest in a business. When they receive something on the order of $840,000 per household, that’s not trivial.”

Breaking American capitalism

Many prominent commentators and economists have endorsed the idea of reparations, but have held back from embracing practical proposals.

Paul Krugman has stated that the policy is “certainly just, but I find it hard to believe it’s going to happen.” David Brooks, a columnist for the New York Times, has written that “reparations are a drastic policy and hard to execute, but the very act of talking about and designing them heals a wound and opens a new story.”

Ethically it’s the right thing to do, but reparations are not necessarily good economic policy or even practically possible, the argument goes. It would be better to institute universal social welfare programs that disproportionately benefit the descendants of slaves, without the difficult national conversations and impossible targeted bureaucratic procedures.

However as historical precedents have demonstrated, it’s by no means impossible. If reparations are ethically right and economically feasible, then what’s the justification for not implementing them?

A comprehensive reparations agenda would entail a massive transfer of wealth at an unprecedented scale, eliminate vast inequalities, rectify hundreds of years of racialization and exploitation, and perhaps most significantly, shatter the meritocratic mythology of American capitalism: that anyone can make it with enough ambition and hard work.

As Ta-Nehisi Coates explains in ‘The Case for Reparations’, “the idea of reparations is frightening not simply because we might lack the ability to pay. The idea of reparations threatens something much deeper – America’s heritage, history and standing the world.”

Slaves built the White House and the Capitol. And as Darity and Mullen told me, many of the US’s largest financial institutions from Lehman Brothers, to New York Life amassed phenomenal profits lending money to and insuring the slave trade and cotton empire.

The monthly reparations checks that my grandmother received helped her financially, but most importantly they represented Germany’s acknowledgment of the atrocities that occurred under the Nazi regime.

Slavery in the US ended in 1865. But still the US government refuses to acknowledge their culpability by paying reparations to descendants of slaves.

Reparations may well break the foundations of American capitalism. And that’s not a bad thing.

Source: openDemocracy