By Kim Whiting, TheReporters.org —

In Tulsa, Oklahoma, not even Martin Luther King gets south of the tracks.

The north side of town encompasses the predominantly Black, low-income neighborhoods and MLK Jr. Boulevard runs right through it. On the other side of the tracks, literally, neighborhoods become affluent, overwhelmingly White, and MLK Boulevard—the same roadway—is instead called Cincinnati Avenue.

It’s merely a change in street name, but it says a lot.

“The message in that is that Whites aren’t going to give praise to a man who promoted justice for all, but especially for Blacks,” says 55-yold Cleo Harris, a fourth generation Tulsan who owns and operates a store near MLK Boulevard. But even more so, Harris believes the delineation is a way for Whites to tell Blacks: “You’re still not wanted on our side of the tracks.”

Even in 2022.

It’s this type of subtle yet destructive racism, as well as the blatantly oppressive laws, policies and unfair practices that Blacks have contended with for generations since Emancipation, that make the seemingly always-controversial subject of reparations even heavier and more complex.

Especially in 2022.

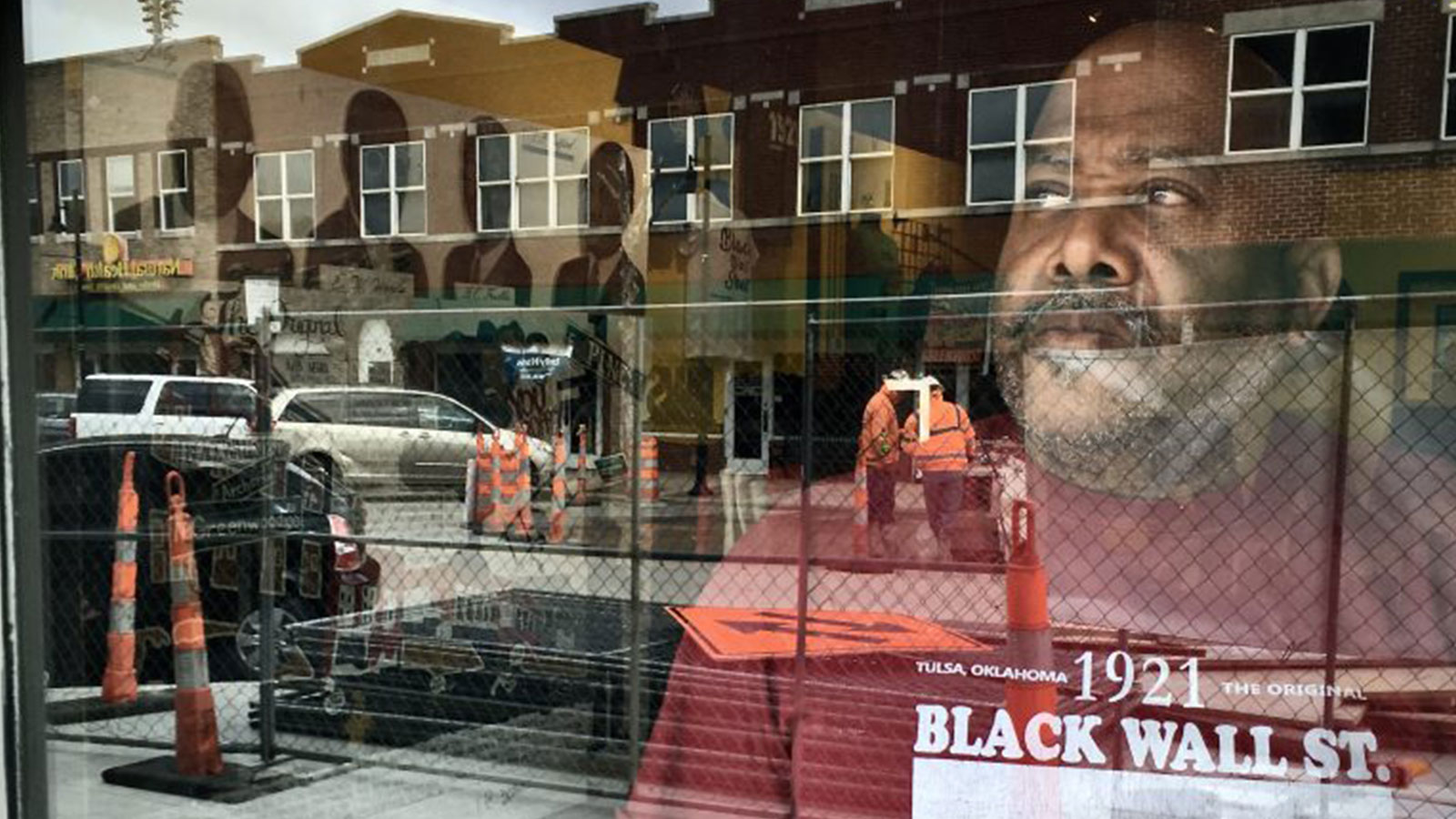

Harris founded and runs Black Wall Street Tees & Souvenirs on Tulsa’s Greenwood Avenue, site of the city’s infamous 1921 Greenwood Massacre. His shop gets its name from the fact that, prior to the massacre, Greenwood’s 35 blocks of Black-owned homes and businesses were so prosperous, they earned the moniker “Black Wall Street.” Harris takes obvious pride in the fact that his great grandfather and seven of his great aunts and uncles were part of that prosperity.

“They had a rough start in life,” Harris explains, “but all of them worked hard and made good lives for themselves.”

Harris’s store features nicely displayed rows of shirts that commemorate and memorialize Black Wall Street, as well as some that honor the citizens the community has produced. There’s one of Harris’s aunt Lelia Foley who became mayor of Taft, Oklahoma in 1973, making her the first elected Black female mayor in the U.S.

Harris’s eyes sparkle, and his words are punctuated with a smile as he speaks, occasionally stopping to warmly greet customers. But his mellow demeanor softens to near-heartbreak when he tells stories about what his family, community, and race have endured over the years.

“This one block,” he says, pointing out his storefront window, “is all that’s left of Black Wall Street. All the rest are White-owned businesses now.”

Cleo Harris is one of many Black Americans who feel the time has finally come for making reparations a reality.

Harris has a history degree from the University of Tulsa, and his passion for Black history and the issues facing Blacks today are obvious as he animatedly shares fact after fact. “I got my associates degree in 2016 and there was little taught about Black history,” he explains. “Almost everything I know I’ve had to learn on my own.”

The belief that American Blacks deserve some kind of monetary reparations for the horrors of slavery, abuse, and discrimination isn’t new, but in recent years the call for reparations in the United States has been bolstered by protests around police brutality and other cases of systemic racism.

In April of 2021, a Washington Post-ABC News poll reported that close to 30 percent of White Americans are now in favor of Black reparations. That was a significant increase from the less than 5 percent of White Americans who supported reparations in 2000—an increase attributed to media coverage on the subject of racism, spurred by the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Massacre, the George Floyd murder and other violence against Blacks.

And then there’s the H.R. 40 bill, a bill that finally made it out of committee last year. The proposed law would establish a commission to “develop reparation proposals for African Americans, by examining slavery and discrimination in the colonies and the United States from 1619 to the present, identifying the role of the federal and state governments in supporting the institution of slavery, forms of discrimination in the public and private sectors against freed slaves and their descendants, and lingering negative effects of slavery on living African Americans and society.”

Still, the bill hasn’t yet been taken up for consideration by the full House of Representatives, even though it has the backing of some of the country’s most prominent Democrats.

Dr. Ron Daniels, the administrator for the National African-American Reparations Commission, believes the federal government has both the means and the ability to pay reparations.

Dr. Ron Daniels, the administrator for the National African-American Reparations Commission (NAARC) adds, “Even if it passes, it won’t be the end. We’ll still have to address the values that led to exploitation, oppression and victimization.”

To fully understand the movement for reparations today, Daniels says Americans need to first contend with the indignities of the past. “In 1863, when newly emancipated slaves were denied the 40 acres and a mule the federal government had promised them,” he explains, “it ensured that they were literally left with nothing, thrown into a hostile environment with no jobs, income, resources, education or land.”

Contrast that to the federal government’s Homestead Act of 1862, a year earlier, that “allotted 160 acres of free acreage to 1.5 million Whites settling in Western states,” Daniels adds.

Reparations scholars William Darity and A. Kirsten Mullen say, “The failure to pay a debt in a timely fashion does not extinguish the obligation, particularly since the consequences of past injustices continue to be visited upon the descendants of the direct victims.” (Photo by Justin Cook)

And as economist Dr. William Darity and folklorist A. Kirsten Mullen point out in their 2020 book From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the Twenty-First Century, “In 1865, when the nation finally closed the door on slavery, it also could have admitted the formerly enslaved to full citizenship. In a deliberate political decision, it chose not to do so. Instead of affirming Blacks’ rights to vote, own property, sit on juries, and have access to public education, measures that would, as President Andrew Johnson once complained at the time, ‘bring them…up to our present level,’ his administration followed his directives to [maintain the imbalance between Whites and Blacks].”

Dr. Kristen Oertel, a history professor at the University of Tulsa, explains that the Jim Crow laws, enacted in the late 19th century to segregate Blacks, “were founded on the premise of ‘separate, but equal,’ but they were never equal. Everything offered to Blacks was far below the standards of what was being offered to Whites,” she explains, “particularly in the area of education. Black children received the message that they were inferior, not equal.”

Jim Crow laws were enforced until the early 1960s, when the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education case desegregated education. Yet many schools in predominantly Black neighborhoods continue to be substandard to this day, increasing the odds that children in those neighborhoods will be underprepared for college and lack the competitive advantage of their peers in well-funded, predominantly White neighborhoods.

Dr. Kristin Oertel teaches African-American history and the history of race and gender in America, at the University of Tulsa.

Store owner Harris tells the story of his great grandmother Mary, born in 1900, “one generation removed from slavery,” he explains. “Mary still struggled to make a life for herself within her limited options and many obstacles. She married a man who was part Native American and entitled to designated land in Arkansas so they moved there.”

Oertel believes that even with their own land, a woman like Mary and her husband still would have had limited economic opportunities. “Cotton farming was the predominant enterprise, and if a person didn’t have enough land for a competitive farm, which the vast majority of Blacks and Native Americans did not, then low-paying agricultural and domestic service jobs were their only options,” she says.

Sharecropping, a system in which a landlord/planter allowed a tenant to use the land in exchange for a share of the crop, was often the only way for Blacks to farm or support their families, but this too created a form of bondage and continued poverty. According to the Equal Justice Initiative, “Within years of Emancipation, discriminatory laws and lending practices largely barred Black people from land ownership…Through sharecropping, White landowners hoarded the profits of Black workers’ agricultural labor, trapping them in poverty and debt for generations. Black people who challenged this system of domination faced threats, violence, and even murder.”

Cleo Harris’s great grandmother, Mary, had the benefit of obtaining and living on land owned by her husband, but their lives were nonetheless very hard in the Jim Crow South.

Harris says the social and cultural climate for his great grandma Mary and her husband were also extremely difficult. The Ku Klux Klan, which was founded a year after Emancipation, had grown exponentially, along with a dramatic increase in violence toward Blacks. Lynchings were at their highest in the 1890s and early 1900s and didn’t decrease significantly until the mid-1930s. This led to a mass migration from the South to the North and West, during which Blacks transitioned primarily from farming to labor jobs, resulting in a huge loss of Black land ownership.

According to a 2019 The Atlantic article, “The Great Land Robbery: The Shameful Story of How One Million Black Families Have Been Ripped from Their Farms,” Black land owners in the South have lost 12 million acres over the past century. In addition to land lost due to Black migration to non-Southern states, they lost acreage from the 1950s onward due to deed of title issues, with The Atlantic reporting that “except for a handful of farmers who have been able to keep or get back some land, Black people in this most productive corner of the Deep South (the Mississippi Delta) own almost nothing of the bounty under their feet.”

It was also in the early 1930s that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt enacted the New Deal, in an effort to recover from the Great Depression. Under the New Deal, the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) offered housing credits to the working class. But the FHA drew color-coded maps of every neighborhood, to indicate “risk,” and those with Black residents were colored red.

Residents in redlined neighborhoods—Black residents—were denied housing credits and essentially then cut off from home ownership. During this same period, 60 percent of the country’s Blacks worked in domestic and agricultural jobs (75 percent in Southern states) so when the Social Security act of 1935 didn’t include those professions, the majority of U.S. Blacks were excluded from Social Security benefits.

After World War II, the G.I. Bill’s mortgage and school tuition benefits for Black soldiers were devalued due to state endorsed and enforced segregation. Harris’s grandfather (Great Grandma Mary’s son) had been a Buffalo Soldier and may well have been a victim of the devalued mortgage and tuition benefits for Black veterans.

Cleo Harris owns a T-shirt and souvenir store in Tulsa, Oklahoma. His thoughts and beliefs about reparations are based on his family’s experiences with racism across several generations.

Harris says he’s certain that his grandfather experienced another obstacle to home ownership. “My dad’s parents–the ones who raised me—came to Tulsa from Arkansas in the mid-1950s,” he explains. “They brought their own milled lumber with them to build a home, and were the first Blacks to build in a White neighborhood. White men were stealing portions of my grandpa’s lumber during the building process, so Black friends armed themselves to protect the property until it was built. As a World War II vet, my grandpa had served his country and yet here were his fellow (White) Americans trying to prevent him from building near them.”

And Harris says he had his own experience with redlining decades later. He explains, “I was with a bank in Tulsa for over a decade, and in 2017 went to them for a business loan. I had already started my T-shirt business, selling from a tent on a corner, and people would come from all over to buy Black Wall Street T-shirts. I was doing well and wanted the money to buy a brick and mortar storefront. The bank told me that because I was with them for years and had good credit, I should be able to get a loan. They pulled up a map on the computer that showed where I live, and I’m sure I wasn’t supposed to see what was on the screen, but there were red flags in my neighborhood. The bank denied me the loan even though I had been faithful about putting my money in their bank for years.

“After I was denied a loan, a local business owner offered to let me sell shirts out of his store. I asked him how he got a store and he told me to speak to the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce [which supports Black-owned businesses in the predominantly Black area of Greenwood, site of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre]. I did, and they gave me free store space for a couple months, until I was able to pay the rent. I now have eight employees and have moved to a bigger storefront, but that wouldn’t have been the case if I had relied on a bank. The Greenwood Chamber of Commerce was my bank.

According to a March 2022 Washington Post article, redlining has done more than perpetuate poverty in minority neighborhoods. A landmark study (published in the Journal of Environmental Science and Technology Letters) found that “compared with White people, Black and Latino Americans live with more smog and fine particulate matter from cars, trucks, buses, coal plants and other nearbyindustrial sources in areas that were redlined. Those pollutants inflame human airways, reduce lung function, trigger asthma attacks and can damage the heart and cause strokes.”

The article also states that although redlining was outlawed more than a half-century ago, “it continues to impact people who live in neighborhoods that government mortgage officers shunned for 30 years because people of color and immigrants lived in them.

During the great Black migration in the early 1930s, Blacks who fled from the South to the San Francisco Bay area were shunned to North Richmond, a town built on a flood plain, and home to the city dump/garbage truck route, railroad lines, and the largest oil refinery on the West Coast. Studies conducted in the 1990s showed North Richmond to be a toxic environment for its residents. Air quality in North Richmond has since been addressed, but by the time the air was made safer, at least three generations of Black Americans had spent their lives breathing hazardous air. Most formerly redlined neighborhoods are still breathing air that is more hazardous than that of more affluent, mostly non-minority neighborhoods.

The physical health dangers inflicted on Black Americans, as well as the emotional and psychological effects of discrimination, add yet more complexity to the topic of reparations. Taken as a whole, those who study and debate reparations always return to the question: How do we ascribe a monetary value to the pain and suffering endured for centuries by Blacks?

At the same time, some who oppose reparations today maintain that present-day Blacks shouldn’t be compensated for atrocities committed generations ago, when those responsible for slavery and those who endured it are long gone.

Harris isn’t surprised by this opposition. He says, “The only victimized race of people who haven’t seen reparations in the United States are Black people. The Japanese received reparations after the WWII internment camps, Native Americans received reparations, the Jewish community received reparations after WWII. The African Americans who built this country should be receiving reparations. This nation’s capitol was even built by slaves!”

But there’s a negative stigma on Blacks, Harris believes, “an attitude that we’re lazy and always nagging for handouts. Non-Blacks don’t see the trauma, the effects of slavery and subsequent injustices that have followed us, and the oppression and violence still going on today.”

Harris points out that Thomas Jefferson, in his Query 14, a letter to the state of Virginia, went into detail about the inferiority of Blacks, ultimately summarizing, “advance it therefore as a suspicion only, that the Blacks…are inferior to the Whites in the endowments both of body and mind.

Former President Ronald Reagan signs the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, granting reparations for the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

“When a highly respected founding father, who penned the part of the Constitution that says ‘All men are created equal’ gives an official opinion that Blacks are inferior,” Harris says, “how does a race transcend that kind of stigma? It has stuck with us.”

Oertel, the University of Tulsa history professor, agrees but adds, “Letters written by Jefferson later in his life show him to have developed a higher opinion of Blacks and a belief that perhaps any deficiencies were environmental, a product of having been forced to live in exceedingly deficient circumstances. Tragically, however, those ideas were found in private letters, and Query 14 was accepted as his official opinion on the subject.”

Journalist and author Ta-Nehisi Coates, who has written extensively on the topics of Blacks in America and White supremacy, testified before the 2019 House Judiciary Committee on the H.R. 40 bill, saying, “Well into this century, the United States was still paying pensions to the heirs of Civil War soldiers…despite no one being alive who signed those treaties.

Authors/activists Darity and Mullen write, “The failure to pay a debt in a timely fashion does not extinguish the obligation, particularly since the consequences of past injustices continue to be visited upon the descendants of the direct victims.” And they estimate that the amount of money it would take to bridge the wealth gap between Whites and Blacks, due to decades of these inequalities and oppressive policies, would cost between $11 and $12 trillion dollars.

NAARC Administrator Daniels adds, “If the 40 acres and a mule had been delivered to emancipated slaves as promised, there likely wouldn’t be a need for reparations today. This is partly because delivering on that promise would’ve recognized that a harm had been done, and for formerly enslaved people to participate in society with any degree of success, they needed land and resources.”

There are also questions as to who exactly should get reparations, how selection will be determined, in what form reparations should be given, and how the distribution should be administered.

Some who oppose reparations, such as U.S. Senate Republican Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, have argued that it would be too difficult to ascertain who to compensate, and by how much. McConnell says the difficulty lies not just in identifying descendants of slaves, or Blacks whose ancestors have suffered injustices, but that determination is complicated further because of what he calls “waves of immigrants” who come to the country and who have also faced “dramatic discrimination.”

In contrast, Darity and Mullen see the selection process as straightforward: “Eligible recipients should be Black Americae descendants of persons enslaved in the U.S., who were denied the promised 40 acres.” They believe that a Black forebear who was at least 10-years-old in 1870 and appears in the U.S. Census by name, but did not appear in the 1860 records, quite likely was born enslaved.

Darity and Mullen say the way an individual makes public their response to the self-reported race question on the U.S. Census could help clarify the matter. They believe a qualified reparations recipient must self-identify as Black, African American, Afro-American or Negro for 12 years prior to the enactment of a reparations program or commission, whichever comes first. Darity and Mullen also recommend that a reparations study commission creates an agency staffed with genealogists to assist in establishing slave ancestry.

Still, some see this plan as being more complicated than straightforward.

In March 2021, Evanston, Illinois became the first city in the nation to approve a government reparations program. The Chicago suburb’s qualifying Black residents are being provided $25,000 toward home down payments or repairs, in order to compensate for what the city describes as decades of housing discrimination. The program is initially budgeted at $400,000, but the first $10 million in revenue from Evanston’s 3 percent tax on recreational marijuana has been designated for the program.

Not everyone is happy about these localized reparations, however. As Darity says, “The wealth gap between Black and White Americans is too enormous to be remedied through incremental programs.”

Sebastian Nalls, a Black resident of Evanston and former mayoral candidate says, “The damage has been done, in that people are looking at Evanston as a nationwide model, looking at this housing program and thinking, that’s [reparations].”

Along the same vein, Evanston Alderman Cicely Fleming says, “True reparations should respect Black people’s autonomy and allow them to determine how repair will be managed, including cash payments as an option. They are being denied that in [Evanston’s program], which gives money directly to the banks or contractors on their behalf.”

Alvin B. Tillery Jr., a professor of Political Science at Northwestern University in Evanston, sees the housing credit program’s shortcomings, but he has a more optimistic view, saying, “I wouldn’t have hoped for this program 10, or even five years ago. I think the conversation is moving forward and more and more people are getting it.”

A recent nationwide upcropping of city and state reparations commissions and plans supports Tillery’s view on the subject. In 2020, California became the first state to create a reparations commission and Asheville, North Carolina pulled $2.1 million from city land purchased in the 1970s (as part of the city’s urban renewal programs that took apart Black communities), and put it toward the creation of generational wealth and economic opportunity for its Black community.

By June of 2021, the mayors of 11 U.S. cities had formed a group pledging to develop pilot reparations programs. “Black Americans don’t need another study that sits on a shelf,” says St. Louis Mayor Tishaura Jones, the city’s first Black female mayor and a member of the group. “We need decisive action to address the racial wealth gap holding communities back across our country.”

And then there’s Tulsa. Ever since the Greenwood Massacre’s 100th anniversary was commemorated last June, debate over reparations and demands for the descendants of the massacre have been highly publicized. Media coverage about the massacre and unmet reparations demands have raised awareness about the injustices and hardships endured, not only by victims and descendants of the Massacre, but by Black Americans for centuries. For some, media coverage of the Greenwood Massacre was their introduction to the topics of generational wealth and the Black-White wealth gap.

“Greenwood was a very successful community because it was a place where Blacks had their own land,” Harris explains. “There was far less obstruction from Whites, and a willingness to help each other succeed. The success of Greenwood, however, is what fueled the resentment and jealousy that sparked the massacre. Whites didn’t like that Blacks were doing well, and poor Whites really resented the many Blacks who were more successful than they were.”

In 1921, Tulsa Whites vandalized, looted and burned Greenwood’s 35 square blocks, also known as Black Wall Street, destroying its businesses, killing up to an estimated 300 and leaving 10,000 homeless. For these crimes, no one was ever arrested or held accountable, and records indicate that almost none of the insurance claims, nor the 96 court cases filed by the Massacre’s victims, resulted in compensation.

At the time, Tulsa’s main newspaper blamed Blacks for instigating and propagating this violence and it was termed a “race riot” for almost 90 years after the fact. After the Massacre,city leaders didn’t assist in rebuilding Greenwood, and in fact government and business leaders worked to thwart redevelopment through discriminatory union laws, building codes, and other unfair policies and practices.

Like many World War II veterans who never spoke of the war, most survivors of the massacre were too traumatized to speak of it (or too afraid to be punished for their views on it)—while the White community avoided discussing it out of shame or discomfort. This meant that no processing, healing or compensating was done until all but the very youngest survivors were no longer living. Despite the fact that repercussions from the massacre continue to this day, only the three living survivors, all now centenarians, have received any kind of reparations. That amount ($100,000) came from a small grass roots organization, not the City.

While the exact number of descendants of the Greenwood Massacre’s victims is undetermined, many of them are not only asking for reparations for loss and damages that their grandparents, great grandparents or great, great grandparents suffered, but for loss of generational wealth that could have provided them with businesses or homes to inherit, money for college, mortgage down payments, and more. This is wealth that would have changed the economic and even social landscape of North Tulsa.

Harris says his Great Grandpa Blaine and seven of Blaine’s siblings lost everything in the massacre. “All of them lost their homes,” he explains. “All of them fled to other all-Black towns in Oklahoma, where they regrouped. They eventually recovered financially to a degree, but I don’t think any of them ever really recovered psychologically. How could they? My Grandpa Blaine was an angry and bitter man until the day he died, and really disliked Whites, largely because of the Massacre and how Blacks were treated by Tulsa Whites even afterwards.”

NAARC Administrator Daniels says, “Imagine how Black Wall Street would be today if it hadn’t been destroyed? Imagine the businesses that would’ve grown from there—for example, Black Wall Street’s Stradford Hotel, which at the time was the largest Black owned hotel in the country. It could very well have grown into a hotel chain. And after the massacre there was urban renewal, which we call ‘Negro removal,’ because gentrification and real estate development displaced residents of Black neighborhoods and destroyed their communities.”

Harris says he saw firsthand how this “urban renewal/Negro removal” happened: “In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a freeway was built right through the middle of Greenwood,” he explains, “which disrupted and demoralized our community, decreased property values, and made it much less pleasant to live in. The same thing happened all over our country. You go to just about any Black area of a city and you’ll see a freeway running through it. The message was that we didn’t matter.”

By the early ‘70s, business had slowed in North Tulsa because of malls and competing restaurants that sprung up South of Greenwood. Greenwood had thrived by keeping its money circulating within the community, so when more dollars were being spent outside Greenwood, prosperity drastically declined. Many of Greenwood’s residents could no longer maintain the upkeep on their homes. In response, government assistance began in North Tulsa, and residents were put in subsidized apartments. Many of them had to sell their land to support themselves and their families and the land was then rezoned for commercial use.

White-owned businesses then purchased much of that land.

Today, only one city block of historic Black Wall Street’s once thriving 35 blocks remains, running down Greenwood Avenue on both sides of the street. It’s owned by the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce and consists of about 10 buildings—Cleo Harris’ business included. But it’s now surrounded by construction.Harris says many of the other 34 blocks have been or are currently being developed into mostly White-centric businesses.

Pointing out his storefront window at new residences across the street, he says, “Those condos were built by a White-owned company, and no Blacks I know would want to live in a place like that. Most couldn’t afford to live there anyway.”

Harris continues, “Over the years, the Greenwood land that once held Black-owned businesses and close-knit Black neighborhoods has been turned into enterprises like the Tulsa campus of Oklahoma State University, a BMX bike course, and the Tulsa Ball Park. Funding was directed toward putting us in subsidized housing, rather than supporting us in retaining our land and developing new ways to thrive economically.”

Conservative Gary Abernathy, who worked in Republican politics in Ohio and West Virginia and is now a contributing columnist for The Washington Post, says his stance on reparations changed as he learned more about the issues. In an April 2021 Washington Post column, he wrote, “Like most conservatives, I’ve scoffed at the idea of reparations. I did not own slaves, so why would I support my government using my tax dollars for reparations? Further, no one in the United States has been legally enslaved since 1865, so why are Black people today owed anything more than the same freedoms and opportunities that I enjoy?…But it is undeniable that White people have disproportionately benefitted from both the labor and the legacy of slavery, and—crucially—will continue to do so for generations to come.”

On the other hand, during the same month that Abernathy pronounced his support for reparations, Utah Congressman Burgess Owens, one of two Black Republicans in the U.S. House, opposed reparations saying “Reparations are divisive. They speak to the fact that we are a hapless, hopeless race that never did anything but wait for White people to show up and help us—and it’s a falsehood.”

Daniels counters, “We have a wealth gap for a reason. This isn’t about Blacks being lazy. There are exceptions, but how much wealthier would Oprah and Bob Johnson (founder of the Black Entertainment Network and the first African American to achieve billionaire status) be if they didn’t have the impediments that White people don’t have? People say if you haven’t made it, it’s because you haven’t worked hard—but Blacks have worked hard and not received their fair compensation and equal pay for a very long time.”

It’s a complicated issue indeed.

In a September 2021 New York Times piece, Darity writes, “Reparations should primarily take the form of direct payments. Examples include Germany’s payments of restitution to the victims of the Holocaust, the U.S. government’s payments to Japanese Americans who were subjected to mass incarceration during World War II, as well as U.S. government payments to families that lost loved ones in the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. But reparations need not be cash transfers. They could take less liquid forms, like trust accounts or annuities.”

Daniels continues, “This also isn’t just about a check. It’s about programs benefitting the Black community. Land is a good example. We still stand with our Native, First Nation people, for not yet—and never being able to—recompense for their losses, but they have land where they can do what they choose, so we say ‘Why not Black people?’”

The National African American Reparations Commission (NAARC) has developed a 10-point plan that goes far beyond simply issuing reparation checks. The focus of the plan is on education, social well-being, health, and economics—on “healing the totality of the Black community,” as Daniels says, rather than individual compensation.

What stands out in the NAARC plan is an infrastructure similar to what the federal government created as compensation to Native Americans, with land designated for their development, conducted at their discretion, as well as governing bodies, enterprises, education, healthcare facilities and banks geared toward benefitting the Black community.

Among the ten ideas outlined in the plan are:

* A request for an apology from the federal government for slavery and other injustices, such as not delivering the 40 acres and a mule to emancipated slaves. (It’s worth noting that an official federal apology would cost nothing, and yet, apart from a 2008 apology in Congress, has never been given.)

* The establishment of an African Maafa Institute/Museum (Maafa being a Swahili term for “disaster, terrible occurrence or great tragedy”) that would educate people about, and memorialize, the horrors and injustices experienced by African Americans for centuries.

* Aid and educational support in repatriation to Africa, for those African Americans wishing to return to their ancestral continent.

* Substantial tracks of land designated to American Blacks that provide the same general autonomy and sovereignty given to Native American reservations. The NAARC envisions these lands being used for education, commercial, economic and health-wellness institutions, to be determined by further subcommittees.

* Funds to be allocated to support the restoration and enhancement of agricultural development, particularly grants and loans to farmers with limited resources, to help them expand and compete in the U.S. and global economy.

* Funds for Cooperative Enterprises and Socially Responsible Entrepreneurial Development.

According to the The Century Foundation, an independent research think tank, impoverished Black neighborhoods have long endured lower-caliber healthcare and, to this day, have less access to care than more affluent neighborhoods. Making matters worse, says Harris, is the fact that care facilities in predominately Black areas have largely been staffed by non-Blacks, whose lack of cross-cultural training and awareness has led them to interactions that are sometimes less than helpful, and even hurtful.

“It’s very difficult to get psychological and sometimes even medical help from people who aren’t Black,” Harris explains. “Sometimes what a non-Black healthcare provider says or does can do more harm than good. Hopelessness is a cancer in our community that fuels the lethargy of depression and addiction, and this can be difficult to fully understand for someone who isn’t Black.”

In response to these kinds of insufficiencies, the NAARC recommends the following:

* Funds for the establishment of a regional system of Black-controlled Health and Wellness Centers, fully equipped with highly qualified personnel and the best 21st century facilities to offer culturally appropriate, holistic preventive, mental health and curative treatment services.

* Funds to strengthen existing hospitals and medical centers serving Black communities, e.g., Harlem Hospital, Howard University Medical Center and the reopening of such institutions that previously served Black communities that closed due to lack of funds.

* Funds to strengthen institutions like Meharry Medical College, and scholarships for students interested in attending these institutions who are committed to providing a period of service to Black communities.

NAARC envisions these programs being implemented in consultation with organizations like the National Medical Association, National Dental Association, National Association of Black Nurses, Black Psychiatrists of America, Association of Black Psychologists, Inc., etc.

Daniels believes the federal government has the ability to pay for all of these ideas. He says, “COVID has shown that when the government needs to write checks, it can write checks.”

Darity agrees, saying, “The federal government’s response to the 2007-2009 Great Recession, and to the current pandemic, demonstrate that it can rapidly mobilize resources and spend huge sums without raising taxes. Federal expenditures to mitigate the economic impact of Covid-19 now exceed $6 trillion. The resources for reparations can be mustered.”

But can our country muster this level of resources? In his 2018 book, The Divide: Global Inequality from Conquest to Free Markets, author Jason Hinkle estimated that the U.S. “benefited from a total of 222,505,049 hours of forced labor between 1619 and the abolition of slavery in 1865. Valued at the U.S. minimum wage, with a modest rate of interest, that is worth $97 trillion today.”

Other formulations are more modest, yet still very steep. According to an August 2020 CNN report, research conducted by Thomas Craemer of the University of Connecticut estimated that proper reparations would cost nearly $19 trillion (in 2018 dollars).

Craemer came up with that figure by estimating the size of the country’s enslaved population between the time of America’s founding and the end of the Civil War, the total number of estimated hours the slaves worked during that period, and the wages at which that work should have been compensated—compounded by 3 percent interest. However, Craemer noted that this doesn’t account for slavery during the colonial period or the decades of legalized segregation and discrimination against Black Americans that followed emancipation.

And then there’s the 2020 study in The Review of the Black Political Economy journal which concluded that, based on unearned wages and interest, the cost of reparations has now reached an astronomical $6.2 quadrillion.

In other words, reparations would be exorbitantly costly and even those in favor of them wonder how they could possibly be accomplished. In August of 2020 (at the very early stages of the pandemic) Michael Tanner, senior fellow at the Cato Institute, told CNBC, “Our national debt is already up to around $26-27 trillion given the money we’re spending on Covid, and we’re losing more money because…economic growth is so slow right now. This hardly seems the time to burden the economy with more debt, more taxes.”

Political pundit and author David Frum, in a 2014 article in the The Atlantic, worried that reparations would become unreasonably complicated. “Within the target population, will all receive the same? Same per person, or same per family? Or will there be adjustment for need? How will need be measured? Will convicted criminals be eligible? If not, the program will exclude perhaps 1 million African Americans. If yes, the program would potentially tax victims of rape and families of the murdered for the benefit of their assailants.”

So many variables to consider, but most opposition to reparations boils down to economics, and Daniels reiterates that the financial aspect of reparations should be a secondary part of the discussion—that the what should be laid out first before details regarding the how are ascertained. “What’s important is giving people a sense of what ought to be done, and understanding will lead to support for reparations,” he insists. “What we try to get people to understand is that there’s no amount of resources that could ever compensate for the crime and terror of slavery, nor the amount of wealth that was extracted by Whites from free labor. This isn’t only about reparations for enslavement, but also the exclusionary culture that came after slavery and still persists to this day.”

Harris also likes the idea of a holistic approach to reparations, saying, “Enslaved Blacks were held back and abused in so many ways, all while building the economy, creating comforts for and lining the pockets of Whites with wealth that they could pass to each new generation. The injustices and abuses my ancestors and other Blacks experienced then and to this day, affect us economically, educationally, psychologically, socially and emotionally, so it is not only appropriate that Blacks today receive reparations, but that those reparations are aimed at addressing it all.”

Gazing again at the construction outside his shop’s window, Harris adds, “Like the Native Americans, and like Greenwood before the massacre, we need land where we can strengthen and recover, without interference from Whites. In my mind, generational wealth has little to do with money and more to do with wellbeing—the security, self-value, identity, cultural pride, hopefulness and emotional and psychological health that Whites, as a race, have generally been able to pass along to their children. We can only rise as high as our self-value, and after all these centuries, I want us to have the space and resources to cultivate these qualities, so that we can pass them along to our children.”

Julian Hast contributed to this article.

Kim Whiting is a Reporters Inc. Board Member. You can read more about her on our Team page. She can be reached at whitingk@cox.net.

Source: TheReporters.org