Often portrayed as an abolitionist, Hamilton may have enslaved people in his own household.

By David Kindy, Smithsonian Magazine —

For Jessie Serfilippi, it was an eye-opening moment. As she worked at her computer, she had to keep checking to make sure what she was seeing was real: irrefutable evidence that Alexander Hamilton—the founding father depicted by many historians and even on Broadway as an abolitionist—enslaved other humans.

“I went over that thing so many times, I just had to be sure,” recalls Serfilippi, adding, “I went in to this with the intention of learning about Hamilton’s connection to slavery. Would I find instances of him enslaving people? I did.”

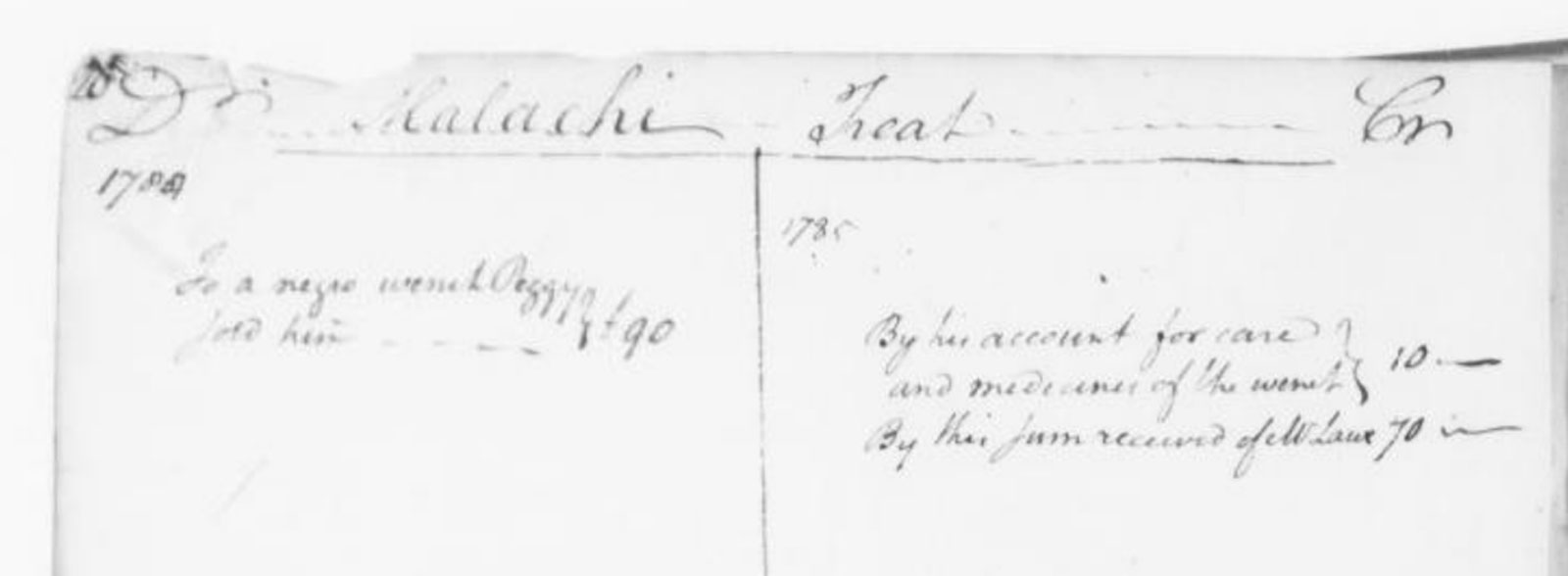

In a recently published paper, “‘As Odious and Immoral a Thing’: Alexander Hamilton’s Hidden History as an Enslaver,” the young researcher details her findings gleaned from primary source materials. One of those documents includes Hamilton’s own cashbook, which is available online at the Library of Congress.

In it, several line items indicate that Hamilton purchased enslaved labor for his own household. While antithetical to the popular image of the founding father, that reference has reinforced the view held by a growing cadre of historians that Hamilton did actively engage in enslaving people.

“I didn’t expect to find what I did at all,” Serfilippi says. “Part of me wondered if I was even wasting my time because I thought other historians would have found this already. Some had said he owned slaves but there was never any real proof.”

One who is not surprised by the revelation is author William Hogeland, who has written about Hamilton and is working on a book about his impact on American capitalism.

“Serfilippi’s research is super exciting,” he says. “Her research confirms what we have suspected, and it takes the whole discussion to a new place. She’s found some actual evidence of enslavement on the part of Hamilton that is just more thoroughgoing and more clearly documented than anything we’ve had before.”

A 1784 entry from Hamilton’s cash books documenting the sale of a woman named Peggy. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Hamilton’s connection to slavery is as complex as his personality. Brilliant but argumentative, he was a member of the New York Manumission Society, which advocated for the emancipation of the enslaved. However, he often acted as legal arbiter for others in the transactions of people in bondage.

Serfilippi points out that by conducting these deals for others, Hamilton was in effect a slave trader—a fact overlooked by some historians.

“We can’t get into his head and know what he was thinking,” she says. “Hamilton may have seen enslavement of others as a step up for a white man. That’s the way many white people saw it in that time period.”

Serfilippi works as an interpreter at the Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site in Albany, New York, the home of Hamilton’s father-in-law Philip Schuyler, a Revolutionary War general and U.S. senator. Her paper came about as part of her research on the many African Americans enslaved by Schuyler. According to the mansion, Schuyler enslaved as many as 30 laborers between his two properties in Albany and Saratoga, New York. Sefilippi initially looked at Schuyler’s children, including Eliza, who married Hamilton in 1780, and as she examined the founding father’s cashbook, the evidence jumped out at her in several places.

One line item, dated June 28, 1798, shows that Hamilton received a $100 payment for the “term” of a “negro boy.” He had leased the boy to someone else and accepted cash for his use.

“He sent the child to work for another enslaver and then collected the money that child made,” Serfilippi says. “He could only do that if he enslaved that child.”

The smoking gun was at the end of the cashbook, where an anonymous hand is settling Hamilton’s estate following his death. That person wrote down the value of various items, including servants. It was a confirming moment for Serfilippi.

“You can only ascribe monetary value to a person you are enslaving,” she says. “There were free white servants who he hired but they were not included there.”

She adds, “Once you see it in his own handwriting, to me there’s really no question.”

An 1893 photograph of Hamilton’s estate, the Grange. Photo caption on photograph reads: St. Luke’s Church, Protestant Episcopal, and Alexander Hamilton’s “The Grange” Convent Avenue and 14st Street (Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

In late-18th century New York, according to historian Leslie Harris, the words “servant” and “slave” were often used interchangeably—especially in New York, where enslaved workers were likely to be members of the household staff. Harris, a professor of African American studies at Northwestern University, points out it is an important distinction in understanding the many guises of slavery in 18th-century America.

“In casual usage, enslavers used the term ‘servant’ to refer to people they enslaved, especially if they were referring to those who worked in the household—the idea of a ‘domestic servant’ could be inclusive of enslaved, indentured or free laborers,” she says. “So in reading documents that refer to people as servants, we have to be careful to find other evidence of their actual legal status.”

Harris is impressed by the research in Serfilippi’s paper and how it is reshaping the way we view the founding father. “It’s clear that Hamilton was deeply embedded in slavery,” she adds. “We have to think more carefully about this [idea of Hamilton as] anti-slavery.”

Hamilton played an important role in the establishment of the American government and creation of many of its economic institutions, including Wall Street and a central bank. The illegitimate son of a Scot, he was born and raised in the Caribbean, attended college in New York and then joined the Continental Army at the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1775. He eventually became aide-de-camp to General George Washington and saw action at the Battle of Yorktown.

Largely self-taught and self-made, Hamilton found success as a lawyer and served in Congress. He wrote many of the Federalist Papers that helped shape the Constitution. He served as the first Secretary of the Treasury when Washington became president in 1789 and was famously killed in a duel with Vice President Aaron Burr in 1804.

Despite being on the $10 bill, Hamilton remained generally ignored by the public until the publication of Ron Chernow’s 2004 biography Alexander Hamilton. The bestseller was read by Lin-Manuel Miranda, who turned it into a watershed Broadway hit in 2015, winning 11 Tony Awards and the Pulitzer Prize.

For the most part, Chernow and Miranda hewed to the accepted dogma that Hamilton was an abolitionist and only reluctantly participated in the sale of humans as a legal go-between for relatives and friends. Though Chernow states Hamilton may have owned slaves, the notion that he was ardently against the institution pervades his book—and not without some support. The belief is rooted in a biography written 150 years ago by Hamilton’s son, John Church Hamilton, who stated his father never owned slaves.

That idea was later refuted by Hamilton’s grandson, Allan McLane Hamilton, who said his grandfather did indeed own them and his own papers proved it. “It has been stated that Hamilton never owned a negro slave, but this is untrue,” he wrote. “We find that in his books there are entries showing that he purchased them for himself and for others.” However, that admission was generally ignored by many historians since it didn’t fit the established narrative.

“I think it’s fair to say Hamilton opposed the institution of slavery,” Hogeland says. “But, as with many others who did in his time, that opposition was in conflict with widespread practice on involvement in the institution.”

A portrait of Elizabeth Schuyler, Hamilton’s wife (Public domain via Wikimedia Commons).

In an e-mail, Chernow applauds Serfilippi’s “real contribution to the scholarly literature” but expresses dismay over what he sees as her one-sided approach to Hamilton’s biography. “Whether Hamilton’s involvement with slavery was exemplary or atrocious, it was only one aspect of his identity, however important,” he writes. “There is, inevitably, some distortion of vising by viewing Hamilton’s large and varied life through this single lens.”

In her paper, Serfilippi cites the work of other historians who have similarly investigated Hamilton’s past as enslaver, including John C. Miller, Nathan Schachner and Sylvan Joseph Muldoon. Hogeland also cites a 2010 article by Michelle DuRoss, then a postgraduate student at the University at Albany, State University of New York, who claims Hamilton was likely a slave owner.

“Scholars are aware of this paper,” Hogeland says. “It’s gotten around. It predates Serfilippi’s work and doesn’t have the same documentation, but she makes the argument that Hamilton’s abolitionism is a bit of a fantasy.”

Chernow, however, holds steadfast on his reading of Hamilton. “While Hamilton was Treasury Secretary, his anti-slavery activities did lapse, but he resumed them after he returned to New York and went back into private law practice, working again with the New York Manumission Society,” he writes. “Elected one of its four legal advisers, he helped to defend free blacks when slave masters from out of state brandished bills of sale and tried to snatch them off the New York streets. Does this sound like a man invested in the perpetuation of slavery?”

For her part, Serfilippi is taking the attention she is receiving from historians in stride. At 27, she is part of a new breed of researchers who are reviewing now-digitized collections of historical documents to take a fresh look at what happened in the past. She is pleased her discovery is shedding new light on a familiar figure and adding insight into his character.

More importantly, she hopes it will help deepen our understanding of the difficult issue of slavery in the nation’s history and its impact on individuals—the slavers and the enslaved. The driving force for Serfilippi was to get to know and remember the people held in bondage by the founding father. She recounts one correspondence between Philip Schuler and his daughter and the potent impact of learning the name of one of Hamilton’s slaves.

“Schuyler, just in letters to other people, will casually mention enslavement,” she says. “In one letter he writes to Eliza in 1798, ‘the death of one of your servants by yellow fever has deeply affected my feelings.’ He goes on to identify the servant, a boy by the name of Dick.

“That was a shocking moment for me. This is the first and only name of somebody Hamilton enslaved that I’ve come across. It’s something I’ve never stopped thinking about.”

Source: This article was originally published November 2020 by Smithsonian Magazine

Featured image: Alexander Hamilton. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Henry Cabot Lodge