By Debbie-Marie Brown, Evanston RoundTable —

Evanston’s interfaith community was among the first groups in the city to speak out in favor of reparations and to offer tangible support. With the city’s program now getting underway, five Evanston churches convened a three-part conference series during the fall with the aim of reinforcing why people of faith are called to support the effort.

Theconference series, called “Faith, Justice & Reparations in Evanston,” featured online presentations in late September and early October from Morris “Dino” Robinson, Black North Shore archivist; Woullard Lett, a national leader in the African American reparations effort; Robin Rue Simmons, the former Fifth Ward council member who spearheaded the city’s reparations plan during her time on the City Council; and an array of faith leaders in Evanston. The Unitarian Church of Evanston led the effort, while Interfaith Action of Evanston was the endorser.

“[I hope] my community walks away with a real understanding that faith communities get that reparation are … called for by us as people of faith; that indeed, this is a part of our core belief system,” said Jacqueline Eddy, one of the event organizers and a member at Northminster Presbyterian.

Eddy was the moderator for the series, which was divided into three topics: the historical and national context for reparations, the history of anti-Black practices in Evanston and the current situation on reparations in Evanston.

Jacqueline Eddy was the moderator for the series on reparations. (Image from Unitarian Church of Evanston presentation)

“Many of the inequities that we see in America today stem from what some have called America’s original sin, slavery,” Eddy said, introducing the workshop on its first day, Sept. 19. “Even after slavery was abolished, rules, laws and institutions were established and kept people of African descent off the ladder of success.” As a result, Eddy added, African Americans as a group lack fair access to health care, education, job opportunities, homeownership, wealth accumulation and any other category that contributes to upward mobility. “What can be done about this? And what can we do? That’s the purpose of this workshop,” she said.

The faith case for reparations

To “ground the conversation in faith,” Eddy said, she introduced the Rev. Dr. Michael Nabors, senior pastor at Second Baptist Church in Evanston and president of the local chapter of the NAACP.

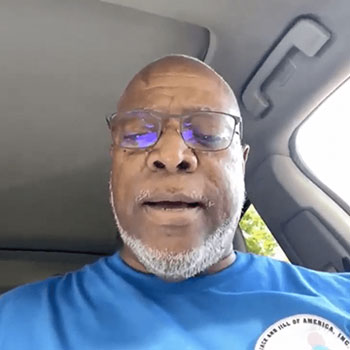

The Rev. Dr. Michael Nabors, senior pastor at Second Baptist Church in Evanston and president of the local chapter of the NAACP, participated in the Zoom session. (Image from Unitarian Church of Evanston presentation)

“Every single faith that has been involved in the discussion about reparations are able to go to their own sacred text, and to find particular passages in their text that talk about the need for us to repair the damage of those who are in our community and neighborhood,” Nabors said on the Zoom call. “And this idea of repair and repairing the damage is very old. And it is connected not only to Christianity and Judaism, but it’s also connected to Islam, to Buddhism, to Hinduism.”

Vanessa Johnson-McCoy, 53, is an Evanstonian and long-time attendee of the majority-Black Faith Temple Church of God in Christ. She is a real estate agent in Evanston and an ardent supporter of local reparations, attending the same congregation as Simmons. Johnson-McCoy had learned about the history of redlining recently, in light of the already active local reparations efforts, but this conference was her first time learning about reparations as a concept supported by an array of faiths. For that reason and more, the workshops impressed her.

“I just didn’t realize that the different faiths felt the same way,” Johnson-McCoy said. “Because you know, kind of as an African American, you almost think like we’re just fighting for ourselves … to see their scriptures in support of reparations, and justice and fairness, and building up those that are down, I was happy.”

Johnson-McCoy said she felt there was unity among the attendees, and that she was encouraged by that.

What are reparations?

Lett, a co-chair of the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America, said reparations are about repair, and followed Nabors with a PowerPoint presentation that set the parameters for the conversation, naming central areas of injury directed toward African Americans paired with remedies.

“Reparations are not about a broken hiring contract, where someone’s labor was stolen,” Lett said. “It’s about a broken human covenant where the very personhood of a people were stolen and degraded through this process of African chattel slavery.”

For full repair to happen, he says, it is not only personal or municipal, but it also must occur at the state and national level, as well as through social corporations and institutions. “Reparations and repair need to happen at many different levels because the injuries occurred at many different levels,” Lett said to the online attendees.

When it comes to local reparations, Lett said a few specific criteria must be satisfied in order to get desired results. “The people who did the plunder, the people who created the injury, cannot be the same folk who define how they should be held accountable for that,” he said. Second, he continued, an independent body should administer the remedy. And finally, he said an independent group should be controlled by those affected, and any solutions they develop should be targeted and specific to past harm.

Local Black Evanston history

The second workshop session on Sept. 26 centered on Evanston’s history of exclusion and was led by Morris “Dino” Robinson of Shorefront Legacy Center, an organization whose mission is to collect, preserve and educate people about Black history on Chicago’s suburban North Shore.

Morris “Dino” Robinson spoke at the second online reparations session. (Image from Unitarian Church of Evanston presentation)

In early Evanston history, the Black population wasn’t centralized and existed in pockets spread across the city, Robinson said. But between 1860 and 1930, the city’s Black population grew swiftly, and that expansion was met with increasing hostility from white citizens, he said.

“There was a concerted effort from 1900 on that slowly pushed the Black residents into one area of Evanston. And we call it now the Fifth Ward,” Robinson said. There weren’t specific rules that identified that Blacks could only stay in one place, but there were an array of informal practices intended to do this very thing.

“They started using coding words like redevelopment or urban renewal or beautification, to bring new development in areas in and target black communities to forcibly move them out. … White residents were instructed not to rent or lease to black residents throughout the rest of Evanston.”

Black residents did not take this treatment quietly, and they protested, Robinson said, presenting the historical account that he unearthed. Black people started trying for positions in city government, he said, and in 1931, vocal desegregationist Edward B. Jourdain Jr. ran a successful aldermanic campaign that landed him at the forefront of the battle for 16 years.

Jim Crow segregation practices paired with Evanston ordinances pushed the Black community into one area and eliminated economic growth, Robinson said. But a growing self-sufficient community in the Fifth Ward still pushed on, he said. Within that area was a segregated hospital, a YMCA, a Black business district, more than 25 Black churches, and dozens of civic and social clubs.

Still, soon maps developed by the federal government led to redlining and codified a permanent Black community, where banks, real estate, and other entities would be discouraged from investing, Robinson said.

“So when you have that happening, at a consistent level, you start making this disparity, which then looks like a black community that is not taking care of his property,” Robinson said. “But when we strip out all the resources, and the banks will not invest in their developments, you depreciate an area, which then leaves a stigma behind. And that carries over from generations to generations.”

What’s responsibility of people of faith?

After Robinson’s presentation, the Rev. Eileen Wiviott, a senior minister at the Unitarian Church of Evanston, introduced an interfaith panel to unpack the responsibilities of local people of faith in light of this history.

On the panel were three local faith leaders: the Rev. Deborah Scott, pastor of Ebenezer African Methodist Episcopal Church since 2016; Rabbi Andrea London, senior rabbi of Beth Emet The Free Synagogue; and the Rev. Michael Woolf, an ordained Baptist Senior Minister at Lake Street Church.

(Image from Unitarian Church of Evanston presentation)

Rabbi London and Rev. Scott both started with a look back at the history of their congregations in the city. “Both here in Evanston and our history as a people, the foundational story of the Jewish people is that we were slaves, and then we were freed. And when we went free, we went free with reparations,” Rabbi London said. She reflected on how the Jewish Evanston community was once concentrated in South Evanston because the corner of Dempster Street is the farthest others would allow the Jewish congregation to go.

How can religious communities continue changing actions and minds? Rev. Scott said to just “show up” and to continue showing up, over and over again. Rabbi London added that many religious traditions are thousands of years old, and change doesn’t happen overnight: “You can’t go to one rally or sign one petition. This is about practice, and religious communities understand that each and every day, you have to practice the faith by what you do.”

The current situation

Former Council member Simmons joined the attendees on Oct. 3 for the final workshop to orient the conversation toward the present. She shared that HR 40, a federal bill to study slavery and reparations for African Americans, passed the Judiciary Committee this past April, for the first time in three decades.

“The bill has been introduced every year since 1989,” Simmons said. “But recently, there have been two important advances since 1989. In 2017 … they rewrote the bill not to just study slavery, but to develop remedy proposals from the impact of slavery and its vestiges.”

Robin Rue Simmons (RoundTable file photo)

Locally, Simmons commented on some of the criticism the city’s restorative housing program has been getting. She notes that much of it comes from the housing program not fitting into a larger pre-determined program. But she challenged that response, and said more energy should go toward planning a more comprehensive plan for redress, and she hopes more city institutions will partner with the reparations effort to push the City Council toward more work.

Said Simmons: “Although this is insufficient as a total program, this is our first step in Evanston. … I will see to it that there’s more to come. … I’m fully committed to improving the work that we’re doing in Evanston.”

Attendees & planners respond

Leslie Yamshon is a 74-year-old educator and Beth Emet member who attended the three reparations sessions. When she first heard about the sessions, she said, her initial reaction was “I’m coming to this,” because she believes faith-based institutions can do things that the government can’t do.

After attending, though, she was surprised to learn the specifics of Black Evanston history. That portion affected her the most. “I’ve lived in Evanston for 44 years. [To learn] about the history in the Fifth Ward, and knowing what happened to what didn’t happen … that’s the most eye-opening.”

Melissa Appelt is with Interfaith Action of Evanston and First United Methodist Church, and she has been organizing the social justice committees at Evanston churches for a few years. She also was moved by the sessions.

“I really am impressed with the way Robin Rue Simmons worked with this concept to put together the reparations program,” she said.

Sarah Vanderwicken, a member of the Unitarian Church of Evanston, was one of the core organizers of the event. She said her hope is that, out of this workshop and whatever it inspires, her fellow white community members can recognize the depth of the harm that other people have experienced, she said.

“By virtue of having good schools, high property taxes, all this lovely stuff, we’re part of the [suburban] fabric that has led to this and that’s what I hope, eventually, people in Evanston can come to deal with “

Source: Evanston RoundTable