“It can be the model for other cities that want to step into the national debate,” Providence Mayor Jorge Elorza said of Evanston, Ill.

EVANSTON, Ill. — This suburban town just north of Chicago will soon start cutting checks to Black people to make amends for Jim Crow era wrongs. The test will be whether anyone follows its lead.

The cash is the latest step in Evanston’s plan to dole out $10 million — in $25,000 chunks — to those who suffered the local sting of housing discrimination, and Robin Rue Simmons’ phone has been ringing ever since the City Council greenlit the money in March.

A former alderman who introduced the reparations legislation in this mostly-white Midwestern college town, Simmons continues to field calls from people around the country who want to know how Evanston pulled off what has eluded so many. From church leaders and corporate executives to a Black organization in New Jersey and an organizer in Detroit — they are all curious how to right the wrongs of the past.

Robin Rue Simmons, former alderwoman of Evanston’s 5th Ward, poses with a photo of her mother, aunt and grandmother in her home. Evanston is a community of approximately 74,000 that is home to Northwestern University. Shafkat Anowar, AP Photo

“There is no question that momentum is building around what we’ve done in Evanston,” Simmons said in an interview.

While California created a commission last year to study statewide reparations, movements to establish them have struggled at the state and federal levels. Efforts in Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, New York and Oregon have slowed or stalled altogether, making Evanston’s government the first to sign off on substantial sums to Black residents in the name of correcting a longstanding racial injustice.

That milestone has given social justice activists a concrete example to wield as they pitch broader reparations to a nation that has wrestled with how — and if — its government should address the systemic wrongs of slavery.

This photo shows a mural painted on the outside wall of Gibbs-Morrison Cultural Center in the 5th Ward of Evanston, Ill. Shafkat Anowar, AP Photo

Victory in Evanston is likely to be measured by cities hundreds of miles away: places like Amherst, Mass.; Asheville, N.C.; Providence, R.I.; and Burlington, Vt. How reparations play out in those cities — and who gets to define what they are — will demonstrate whether Evanston is the model activists envision or an outlier that shows how polarized the country remains in coping with the legacy of racism.

“It takes a progressive, well-educated electorate. So yeah, places similar to Evanston will have more success,” said Alvin Tillery, Jr., director of the Center for the Study of Diversity and Democracy at Northwestern University, comparing it to conservative enclaves least likely to take reparations seriously. “Asheville and Burlington are more similar to Evanston than Cherokee County, Georgia, or where [Texas Rep.] Louie Gohmert serves.”

And if reparations are ever to become a real goal for Washington or statehouses, it will be places like Evanston that laid the political and policy groundwork to make it happen.

In Detroit, Keith Williams, chair of the Michigan Democratic Party Black Caucus, is quietly leading an effort to collect the 3,400 signatures by June 15 to put reparations on the city’s 2021 ballot.

“You saw Black Lives Matters signs in front of homes in white neighborhoods,” he said in an interview, noting how he was “inspired” after hearing about Evanston’s decision.

The language Williams is pushing would establish a committee to create a reparations fund and make recommendations on how to allocate money to those affected by racially restrictive covenants and housing discrimination.

Putting money in

What distinguishes Evanston’s program is that it comes with cash, and during an economic recession no less. It’s tailored to Black people who can demonstrate their ancestors either lived in the city between 1919 and 1969 — when racism was a matter of official policy — or can show they faced housing discrimination during that time. The funds are also purpose-driven: The $25,000 is specifically for buying a home or improving one they have.

Simmons and racial justice activists see the city’s move, which will dole the money out over 10 years, as the start of a grassroots effort that might eventually spur Congress to enact a federal reparations law. There’s precedent for small towns leading a national change. Desegregating the bus system in Montgomery, Ala., started with Rosa Parks’ iconic protest, and interracial marriage had dozens of small victories before the Supreme Court came around in 1967. Simmons also points to the more recent Ban the Box effort to remove criminal background checkboxes on employment applications that started in Hawaii and spread to Minnesota, Illinois and other states.

“Local initiatives have a history of inspiring Congress and communities to pursue and advocate and take action on long-overdue justice legislation in the United States,” said Simmons, who now sits on the New York-based National African American Reparations Commission.

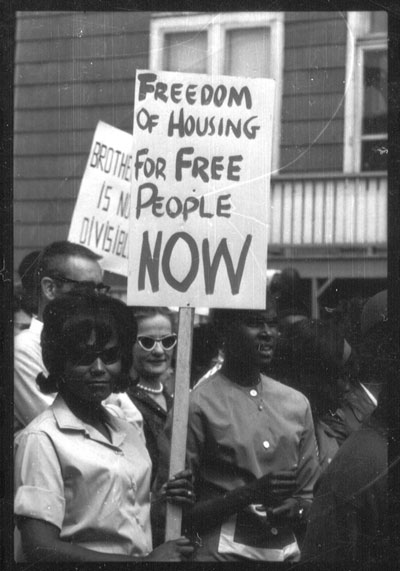

Marchers at a 1964 protest for fair housing in Evanston, Ill. Courtesy of Shorefront archives.

Reparations aren’t new in the U.S. In 1988, the federal government disbursed more than $1.6 billion to more than 82,000 Japanese Americans who endured internment in this country during World War II. The reparations law signed by then-President Ronald Reagan admitted that internment was based on “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”

A congressional committee advanced reparations-related legislation, H.R. 40, for the first time in April. But it’s unclear whether the bill, which would set up a commission to study the issue and the U.S. government’s role in African American disenfranchisement, might reach the House floor. Its odds in the Senate are essentially zero.

Activists worry Democrats in the House won’t move forward with the measure for fear it would jeopardize 2022 midterms.

“Winning elections plays a big role in causing things to happen. It’s important to maintain the majority so that you can make some things happen in the next round,” said Rep. Danny Davis (D-Ill.), who sees the issue gaining momentum anyway. “I’m optimistic. It’s been slow, but change is oftentimes slow. And it’s more evolutionary than revolutionary.”

Until the federal government embraces an approach to reparations for its part in slavery, smaller municipalities seem eager to experiment after Evanston made headway.

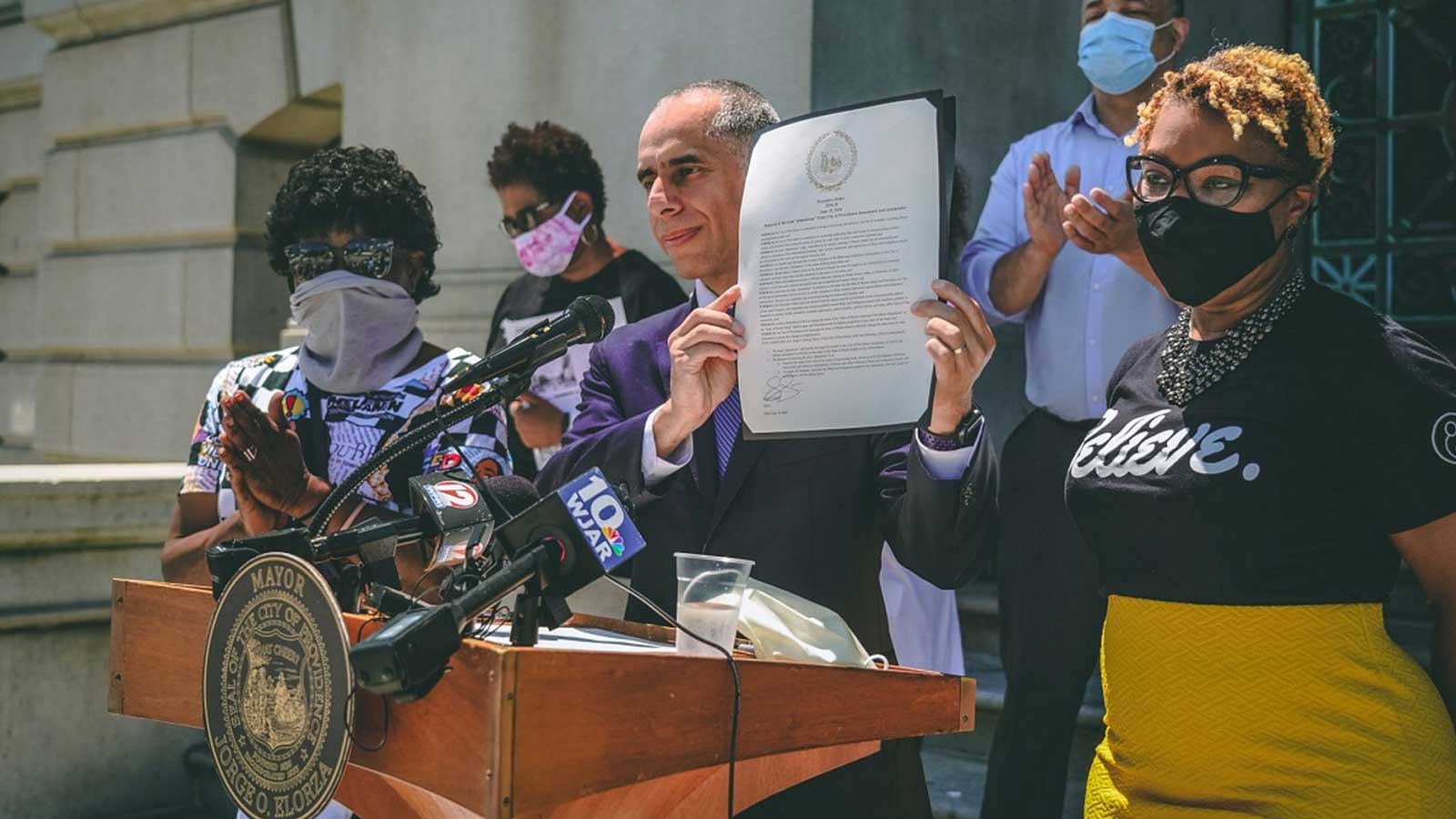

“It can be the model for other cities that want to step into the national debate,” Providence Mayor Jorge Elorza said in an interview.“Race relations in this country has been a divisive issue since the Constitutional Convention and … as a country, it’s something we’ve never fully addressed head-on.”

Providence released a report earlier this year on the history of Black and Indigenous injustice in the New England city as part of what Elorza calls a first step in a reconciliation process. The city followed up with a request for proposals to talk with voters about the effects of those injustices and what might be done now.

The final phase — reparations — has proven to be the most challenging for Providence for the same reasons places like Asheville and other cities get stuck: cost.

“Finding money for this at the municipal level is a challenge in North Carolina because cities have very limited options for generating new sources of revenue,” said Julie Mayfield, a former Asheville City Council member who now serves in the state Senate. “Asheville is using all of the authority it has to generate revenue and really the only option that the city has to raise a lot of new revenue is to increase property taxes. And at this point, that is a challenge.”

Some faith groups have urged congregations to consider reparations, a message that’s resonated particularly strong with Episcopal and Protestant churches that had a greater role in slavery. And a few schools have raised the idea after facing pressure to tackle their racist roots — most notably Georgetown University, which announced plans in 2019 to build a fund for descendants of enslaved people it sold in 1838.

Providence (R.I.) Mayor Jorge Elorza signs a community-driven Executive Order to remove Plantations from City documents and oath ceremonies in June 2020. Courtesy of Jorge Elorza’s office

“As more organizations look at this — faith groups, businesses, universities — I think more people will come around,” said Michele Miller, co-founder of Reparations For Amherst, an organization she formed with Matthew Andrews in wake of the George Floyd killing by police last year.

The two approached the council in the small Massachusetts town to draft a resolution condemning racism, and three council members worked on the effort.

Last week, the town council’s finance committee proposed creating a fund for reparations using $209,000 in reserves out of the next budget, a move that requires support from two-thirds of the full council and is slated for later this month. An African Heritage Reparation Coalition recently approved by the council will then develop more proposals for generating money in future years.

Are reparations only about slavery?

Sorting out who should receive reparations and how they can be distributed is often a complicated and emotional process. If the traditional concept of reparations is to compensate people for slavery, it remains unclear how a government should account for the compound interest accrued over another century of Jim Crow and episodic racial terrorism.

Lynching, Jim Crow, red-lining, police abuses, predatory lending practices and mass incarceration are all “crimes against humanity and egregious acts against the Black community that are in need of redress,” said Simmons, the former Evanston council member.

As the discussion of reparations shifts from theory and into the policymaking realm, the meaning of reparations becomes more urgent: Is it an apology to Black people who are descendants of slaves? Or is it a monetary commitment to improve educational and other disparities? Who decides who qualifies?

Burlington, Vt., approved forming a task force in 2020 to study possible reparations for the descendants of slaves and Tyeastia Green, the city’s inaugural director of racial equity, said it’s important to decide on a definition.

“I want to make sure none of these cities and towns are saying, ‘We provided reparations, so we’re done and we’ll move on,’” Green said. “That’s dangerous to do because you’re not actually accounting for financially and economically what happened here in this country up until 1865.”

Source: Politico