The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968. Four days later, Civil Rights Warrior and Congressman John Conyers Jr. took to the floor of Congress to insist on a national day of recognition to honor his memory. It took 15 years of struggle before the day was finally celebrated as a federal holiday.

Martin Luther King, Jr. (Source: Unsplash)

Three years later, in 1989, Conyers introduced H.R. 40 – The Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African-Americans Act – and that struggle has gone on even longer. Last April the bill finally made it out of committee, the culmination of decades of work, mostly by Black people. The 40 in H.R. 40 has significance that goes beyond the order in which it was introduced to Congress. It’s meant to remind us we’ve never made good on the country’s promise to give formerly enslaved African Americans 40 acres (the mule would come later), following emancipation.

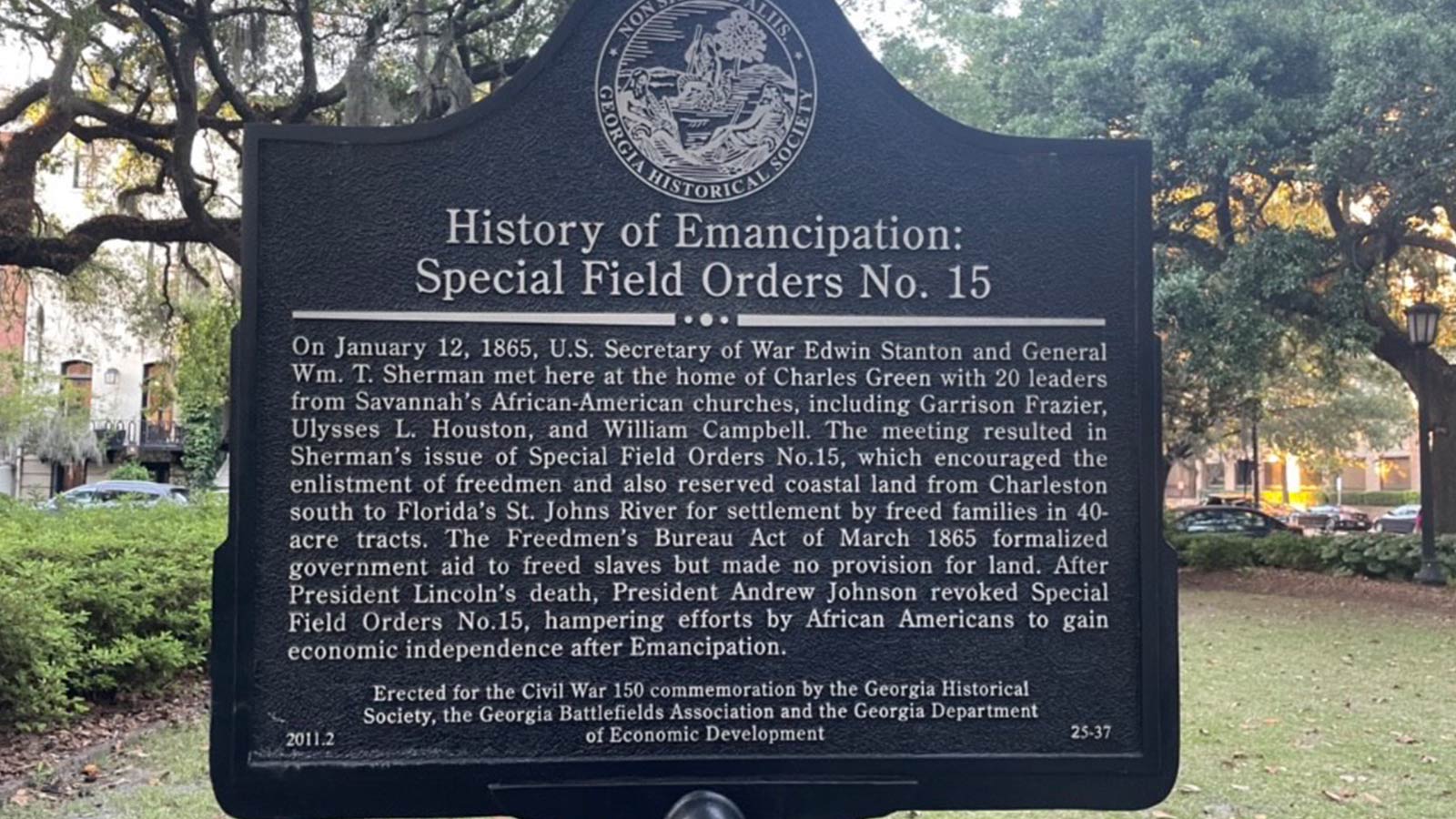

Special Field Orders No.15, issued on January 16, 1865 by General William T. Sherman (with the approval of President Lincoln) came at the urging of 20 Black leaders, mostly ministers, in Savannah. Here is the section of the order that addresses the land grant:

” ..each family shall have a plot of not more than (40) acres of tillable ground, and when it borders on some water channel, with not more than 800 feet water front, in the possession of which land the military authorities will afford them protection, until such time as they can protect themselves, or until Congress shall regulate their title.”

The order was accompanied by other specifics identifying the territory that was being granted and ordering that it would be settled and governed entirely by Black people. By June, 1865, “40,000 freedmen had been settled on 400,000 acres of ‘Sherman Land’” and a Black governor – Baptist minister Ulysses L. Houston – had been appointed.

In a devastating turn of events, in the fall of 1865, the order was revoked by President Lincoln’s successor, a supporter of the southern white supremacist establishment, Andrew Johnson. The land was returned to its former slave-holding owners, and 40,000 Black freedmen and their families were left without a home.

(A little known fact is that three years prior, the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act made reparations to the owners of enslaved people for their “loss of property” by granting them the equivalent of $8,000 in today’s dollars for every slave who was freed.)

Why does a broken promise to formerly enslaved African Americans in 1865 matter now?

So much of the focus of whites has been related to the harm suffered by African Americans as a result of slavery and post-slavery structural racism. We’ve read eye-opening opinion pieces and books, listened to illuminating podcasts, and even talked to Black friends and co-workers about their experience of being Black in America. I bet most of us in Amherst can appreciate the magnitude of these crimes against humanity and can sympathize with the physical, mental, and emotional consequences for people of African descent.

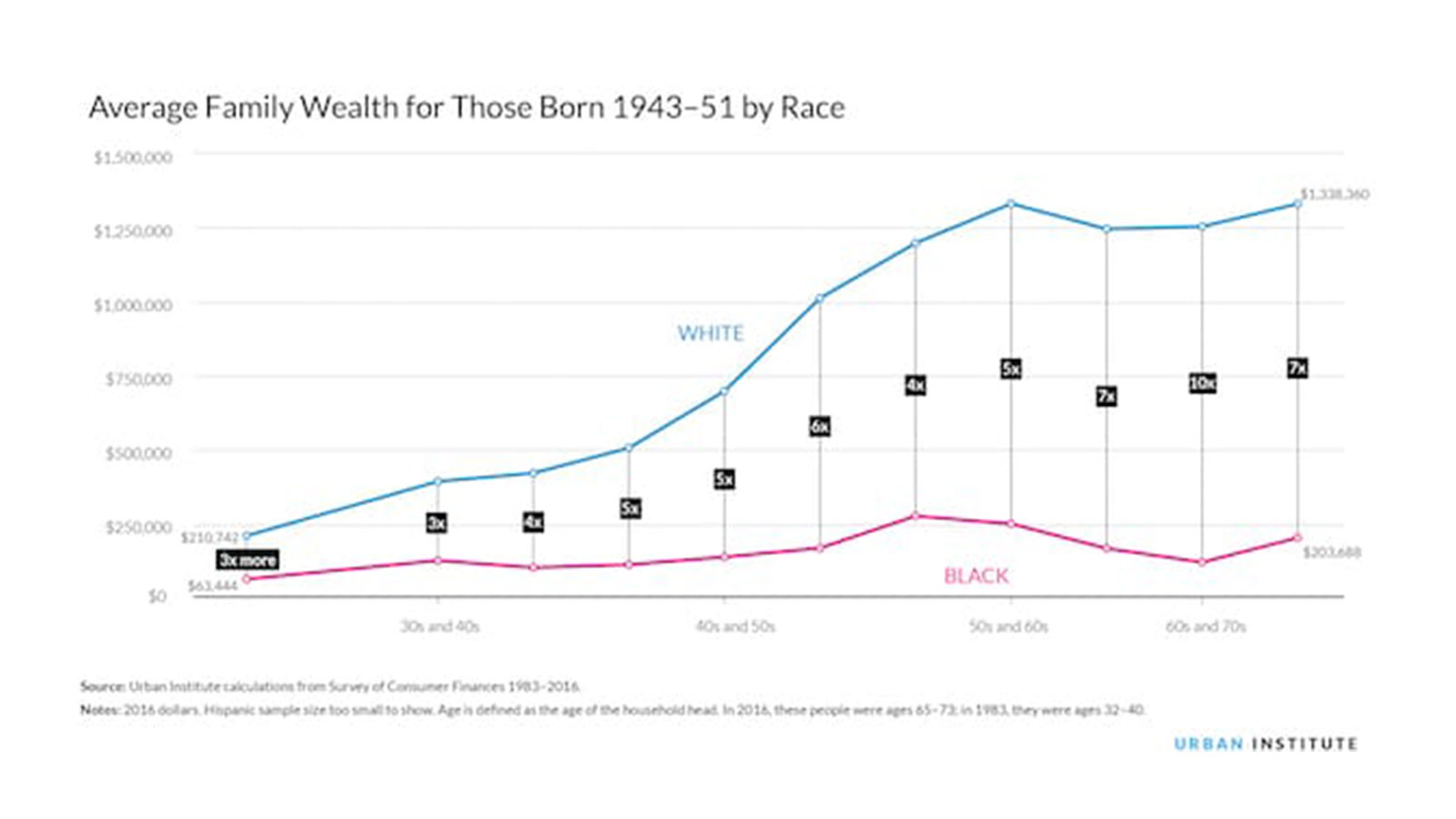

But how much have we thought about what Black people have lost as a result of broken promises by white government leaders and racist federal policies that excluded Blacks from accessing land and other wealth-building resources? What would America look like today, and what would the financial condition of the Black community be like, if Sherman’s order had stuck?

Some economists have estimated the value of 40 acres and a mule for those 40,000 freed slaves to be worth a staggering $640 billion today.

To add to the repugnant and unequal treatment of Black people, between 1862 and 1935, The Homestead Act provided mostly white people (99.73%) up to 160 acres of free land. According to Shawn Rochester, in his book “The Black Tax,” this equates to roughly $1.6 trillion in value today (the equivalent of giving $500,000 to $1 million per family). Further, Rochester tells us it’s estimated that up to 93 million Americans today are direct beneficiaries of this government-enacted wealth-building program.

Dr. King poignantly encapsulated this in a 1967 interview, saying “Emancipation for the Negro was really freedom to hunger. It was freedom to the winds and rains of Heaven. It was freedom without food to eat or land to cultivate and therefore was freedom and famine at the same time.”

Reparations, apart from racial justice initiatives, are the way forward for the U.S. to pay the debt owed to African Americans. White support and follow-through are essential to this process, not only in word, but in deeds. No more broken promises. No more racist policies that favor whites. No more.

No matter how robust a reparative justice initiative is, it’s impossible for a locality to settle the debt owed to Blacks. It’s the responsibility of the federal government to settle up – financially and morally – with African Americans, and that’s the goal of H.R. 40.

In Amherst, however, we can begin a process of healing the wound and giving folks an experience with making reparations that will, like other social movements that begin locally (think marriage equality), support the national movement. While financial reparations are necessary at the federal level, locally we can create an opportunity for Black residents to design a reparative plan that comes in many forms and, importantly, benefits all residents.

What that program looks like and who will be eligible is still a mystery and, ultimately, can only be decided by the African heritage community of Amherst.

According to N’COBRA (National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America), reparations can be made to an individual through “direct benefits” like housing assistance, educational scholarships, and business grants. And, to the Black community as a whole through “collective benefits” aimed at collective repair and healing. Examples they give are African-centered education, community trust funds, community wellness initiatives, and ending racially based public policy.

To ensure these benefits hold up to legal challenges, the African Heritage Reparation Assembly will develop a narrowly defined harm report which links specific harm that occurred in Amherst, like racial deed covenants that existed on some of our streets, to determine the impact for Blacks who currently live or have lived in Amherst. This information will help to inform the Black community as they design the Reparative Justice Program for Amherst.

In May 2021 the Town Council voted to create a reparations stabilization fund and to form a committee to study and develop reparation proposals for people of African heritage in Amherst. This is one of several actions the Town has taken to further the goals of the resolution to “End Structural Racism and Achieve Racial Equity for Black Residents” adopted by the Town Council December 7, 2020.

Michele Miller is a member of the Town Council from District 1 and is chair of the African Heritage Reparation Assembly.

Source: The Amherst Current