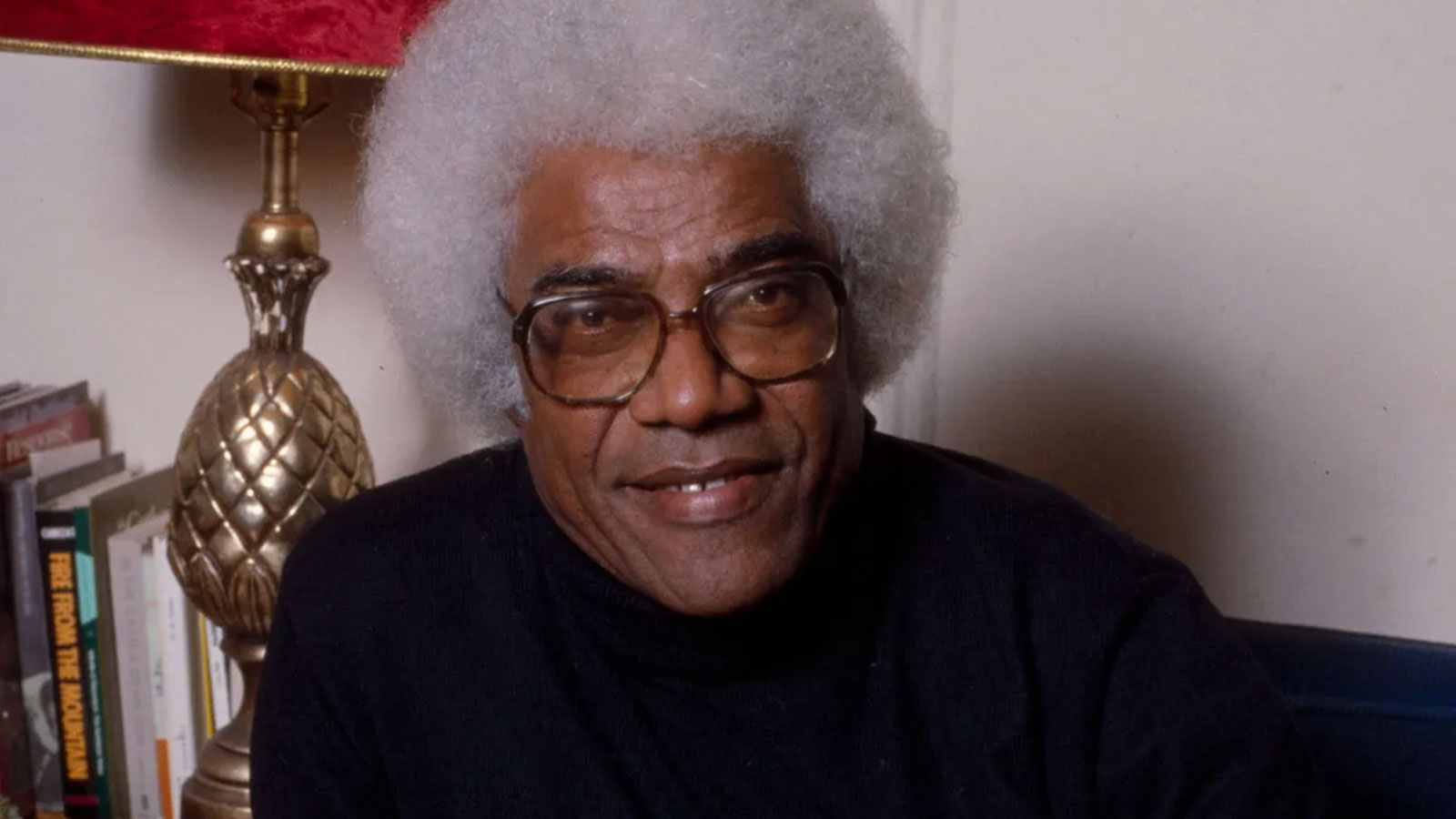

This edition of Reparation Conversations pays respect to George Lamming, by presenting excerpts from the 2014 George Lamming Distinguished Lecture, which was delivered by Professor Verene Shepherd at Errol Barrow Centre for the Creative Imagination, Barbados.

***

Professor Verene Shepherd

Thank you, Chair, for your kind introduction. I feel quite honoured to have been invited to deliver this important lecture, in the presence of the honoree. His work in a very real sense created a space through which the emergence of the unique Caribbean identity flourished. The lived experiences of our people were explored through his novels, poems, and essays, which have bases in the oral narrative tradition, encapsulating our shared history of slavery and colonialism and the identity crises derived from it, leaving each of us to look within the castle of our own skin, for the royalty within.

It is fitting that Lamming should have this lecture series in his honour. I, like others who use historical novels to understand the representation of the Caribbean, can truly say to him, like Marlon James’ night women in the novel of the same name, ‘thanks for the history I learned and the history I had to unlearn’ through the discursive lens you chose, to view the issue of colonialism and its legacies.

The lecture, ‘Reparation, psychological rehabilitation and pedagogical strategies’, was not only decided on in response to the request of the hosts for a lecture on the issue of reparation, but emerged out of my lifelong preoccupation with the issue of what it means to be a person of African descent in a racist Western world.

Although many in the Caribbean and the diaspora have only recently been paying attention to the issue of reparation for native genocide, Caribbean slavery, deceptive Indian indentureship and continuing legacies, the struggle for reparatory justice has a long genealogy. The pioneers were the First Nation Peoples; and later enslaved Africans all over the Caribbean, who knew their illegal entrapment in Babylon was a violation of their human rights and struggled to end the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans and chattel enslavement.

Took Up Struggle

In the immediate post-slavery period, the newly emancipated and imported contract labourers took up the struggle, enforcing ideas of moral economy in their efforts to secure land and decent wages for decent work and political self-determination. Langston Hughes could very well have been talking about justice activists when he wrote in ‘Democracy’:

I have as much right

As the other fellow has

To stand

On my two feet

And own the land

I tire so of hearing people say

Let things take their course

Tomorrow is another day

I do not need my freedom when I am dead

I cannot live on tomorrow’s bread

The most vocal post-1930s advocates for reparatory justice were the Rastafari, whose claim was for African redemption and repatriation. They were later joined by individual politicians, NGOs, academics, civil society and finally, the Heads of Government of CARICOM, who established the CARICOM Reparations Commission, national commissions, etc., (Jamaica since 2009) and a Prime Ministerial Subcommittee on Reparations, comprising the Heads of Government of Barbados, St Vincent & the Grenadines, Haiti, Guyana, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago to whom the CRC reports. The Ten Point Plan crafted by the members of the CRC sets out the rationale for reparation, identifies the victims, and the perpetrators of crimes against humanity.

Ten Point Plan

The Ten Point Plan, framed within the right to development, acts as a blueprint or strategy for claiming reparation. Many agree that the pressure of development has driven Caribbean governments to carry the burden of public employment and social policies designed to confront colonial legacies. Amartya Sen argues in his 1999 book Development as Freedom, that overcoming these socio-economic problems is a central part of the exercise of development and of the process of ensuring that freedom, that will otherwise fall at the feet of underdevelopment.

Rohan Kariyawasam, in his contribution to the collection of essays, Colonialism, Slavery, Reparations and Trade: Remedying the Past?, argues that while other strategies for remedying past atrocities might not work – such as the legal route – the Right to Development framework (conceptualised by the Senegalese jurist Keba M’Baye in 1972 and reformulated into a declaration by the UN about 10 years later) would facilitate technology transfer and trade agreements. According to him, the historical transgressors should be made to invest in the affected countries in technical skills, technology, research & development, education, health and services; and the RTD should be a legally enforceable right to be upheld by transgressors.

Psychological Rehabilitation

I wish to focus on psychological rehabilitation, said to be vital because of the impact of slavery and colonialism on the psyche and behaviour of African people. In his Black Skin, White Mask, Franz Fanon analysed the impact of colonialism and its deforming effects, and argued that white colonialism imposed an existentially false and degrading existence upon its black victims, to the extent that it demanded their conformity to its distorted values. Evidence that this history has inflicted massive psychological trauma upon African descendant populations in the Caribbean and in the diaspora is all around us. Joy Degruy Leary frames it within the context of “post-traumatic slave syndrome”.

In our region we see skin bleaching, damaged self-confidence expressed though social comparison and ranking in our communities; the denigration of blackness. We maintain ranking in our school system because we have not rid ourselves of structural or indirect discrimination in education. Yes, colonialism has disfigured us and we need to use all means at our disposal, including a reparatory justice programme, to rehabilitate ourselves.

Feelings of cultural loss and social alienation have long been expressed by our literary luminaries, especially where they have been writers in exile. Lamming himself would write that:

When I review these relationships they seem so odd. I have always been here on this side and the other person there on that side, and we have both tried to make the sides appear similar in the needs, desires, and ambitions. But it wasn’t true. It was never true …. I am always feeling terrified of being known … They won’t know the you that’s hidden somewhere in the castle of your skin.

Pedagogical Strategies

The question is: what are the pedagogical strategies that reparation advocates will have to employ? I cannot go into all the strategies, but I will say this: the greatest weapon in this arsenal will have to be culturally relevant/anti-colonial education, especially history education. For the surest way to defeat the reparation movement is to ensure our children remain ignorant of their past and the legacy of activism around issues of justice and human rights for which their/our ancestors fought. Postmodernists ask: whose history gets told? In whose name? For what purpose? But teach it/tell it we must, especially if we believe that education is liberation. As President Barack Obama said,“memory is not only about the past; it is about securing the future”.

Featured image: George Lamming, c. 1988. Bernard Gotfryd Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.