University officials say it has been helping descendants and a reconciliation fund will begin considering grant proposals this spring.

By Susan Svrluga, The Washington Post —

Georgetown University student leaders are pressing the school to actmore quickly on a promise to help descendants of enslaved people sold in the 19th centuryto pay off debts at the school.

Nile Blass, the student body president, said she thinks most students assume the university has been donating money since it first announced in October 2019 that it would commit at least $400,000 annuallyto fund community-based projects to support descendant communities.

The school’s promise followed a student referendum in 2019 and protests calling for reparations that drew widespread attention amid a national reckoning over race and reconciliation.

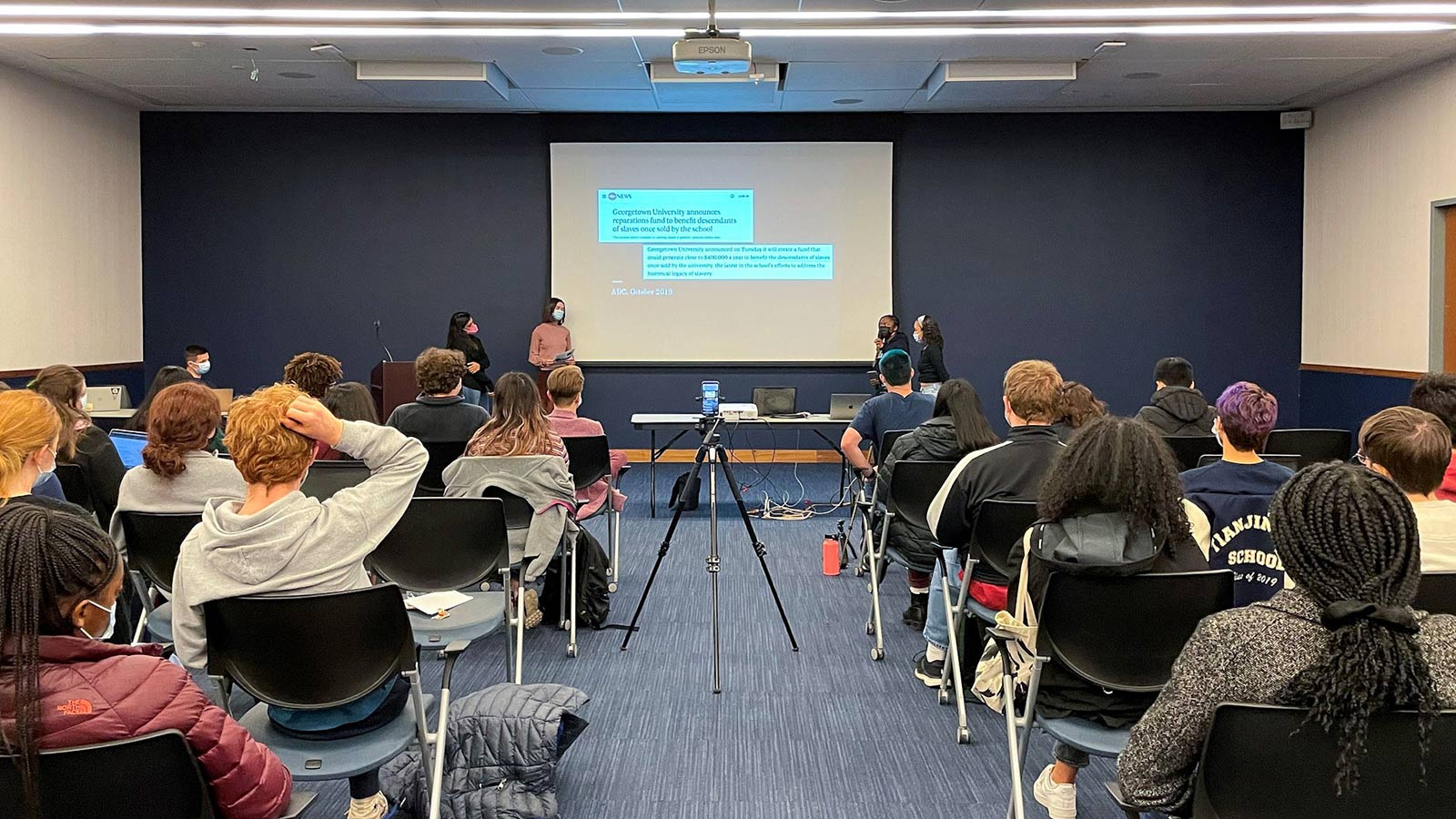

Blass and other students recently held an event highlighting what they called Georgetown’s broken promises to the descendant community. The school pledged tangible reparations, the students said, but two years have elapsed. “Spoiler alert: Nothing has happened,” they told a room full of students and an audience watching on Zoom.

“Where is the money?” they asked. “Was it all a publicity stunt?”

The university says it has been working to help descendants. A university spokeswoman, Meghan Dubyak, said this week thatthe reconciliation fund effort was delayed by the coronavirus pandemic. But money has been set aside for a launch this spring of a grant-review committee and grant application process, she wrote in an email, and planning for a spring fundraising campaign is underway.

Student leaders will meet with administrators in January, Dubyak wrote in an email, and will draw on some lessons learned this fall when the school set aside $100,000 for hurricane relief. Georgetown says it is working with the Southern University System Foundation and the Foundation for Louisiana to provide grants to areas affected by Hurricane Ida with a “focus on communities where descendants live.”

There is often tension on campuses between student activists demanding rapid change and administrators putting policies in place. Students, whose time in college is limited, worry that causes can lose urgency and get swept aside when advocates leave. And school officials in many cases caution that lasting change can require legal structures or widespread buy-in that requires extensive groundwork.

Genevieve Grenier, a sophomore active in student government, said many students had lost sight of the effort because some of the initial activists havegraduated and the pandemic upended things on campus. But she said she was encouraged by administrators’ response this week, and student leaders will learn more about efforts at a meeting in January. “We all have to hold the institution that we’re a part of accountable,” she said.

Students at Georgetown University listen to a recent presentation about reparations for descendants of enslaved people. (Bella Fassett)

The university, like many others, has been confronting its history in recent years. The revelation of the 1838 sale of272 enslaved peoplecontinues to reverberate, with efforts to learn more and to help descendants. The university has launched scholarly efforts, memorials and other efforts.

Two Jesuit priests who served as presidents of Georgetown orchestrated the sale, a decision that provided a crucial infusion of cash to the university but tore families apart and sent people to labor in cruel conditions on cotton and sugar plantations in Louisiana.

Thousands of their descendants have been identified.

In 2015, after student protests, the university removed the names of the priests from two campus buildings.

In 2017, Georgetown, the Archdiocese of Washington and the Society of Jesus (the Roman Catholic order better known as Jesuits) apologized for their role in the slave trade. The university promised an admissions boost to descendants, and renamed a residence hall after a man who had been enslaved.

Some students and descendants have called for the university to do more.

Video: Georgetown students voted April 11, 2019, to pay a fee benefiting the descendants of enslaved people who were sold to pay off the school’s debts. (WUSA9)

Student activists worked for months to develop and promote a plan to help descendants of the 19th-century sale. In the spring of 2019, they voted for a student fee to raise about $400,000 for a nonprofit led by a board of students and descendants that would donate to charitable causes benefiting descendants.

While some objected to the idea of reparations, or of students already burdened by tuition costs paying for the university’s past actions, two-thirds of the undergraduate students who voted in the student-government referendum supported the measure.

The vote was nonbinding. By the following fall, activists were protesting, calling on university leaders to take action.

During a protest in October 2019, Georgetown University students call for the implementation of a student fee to pay for reparations to the descendants of enslaved people sold by the university in the 1800s. (Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post)[/caption]

In the fall of 2019, university President John J. DeGioia announced that the school would raise $400,000 a year in donations to fund projects, beginning in the fall of 2020-2021, to benefit descendants.

The university’s plan differed from that voted on by students in a few ways. A key change: The fund would be financed through fundraising rather than from student fees.

Students for GU272, the activist group, saidthe administration’s plan directly negated the wishes of students, by taking over the effort and turning it into a philanthropic effort rather than treating it as a debt to be repaid and an opportunity for reconciliation. The student group also said the university’s plan did not have any transparency around its implementation and accountability.

A university spokeswoman said at the time that the school would be taking “actionable steps” in the monthsafter the announcement and would engage in an “inclusive process that builds upon the ideas of the student Referendum.”

Meanwhile, talks had been underway with descendants.

During a protest in October 2019, Georgetown University students call for the implementation of a student fee to pay for reparations to the descendants of enslaved people sold by the university in the 1800s. (Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post)

In March of this year, Jesuits and a group of descendants announced the creation of a $100 million fund to help descendants, and pledged to try to raise $1 billion through private donations. Georgetown supported the establishment of the Descendants Truth & Reconciliation Foundation with a $1 million gift that helped initial planning.

In announcing the news of that foundation in March, DeGioia said that a “shared vision for a Foundation was a first priority for Descendant leaders in the steps toward reconciliation,” and that conditions were now in place to accelerate work on their $400,000 annual commitment. Their aim was to distribute their first grants this year, he told the campus community.

Dubyak said the money Georgetown has committed would be awarded for community-based initiatives, inviting descendants to help create and implement projects and activities that support their communities. She said those initiatives would partner with and benefit a broad community, “such as developing a new preschool program or health-care initiative, with a long-term impact.”

Julia Thomas, a member of the GU272 advocacy group, said she remembers finding out in 2016 that her ancestors had been sold. The revelation was shocking, she said, and sad.

She wished her family had known about it sooner, before her grandfather died.

In coming to Georgetown, where she is a sophomore, she said, “I felt like I had a purpose to honor the legacy of my family, and do everything that I can for the descendants.”

Thomas said the university’s statement on how it plans to move forward with the reconciliation fund was helpful in providing a time frame, but “somewhat vague and uninspiring because they didn’t specify how these funds would be allocated.”

Thomas added: “It is important to hold the university accountable for benefiting from the sale by creating a system that forms an everlasting relationship between descendants and the university. That’s what the referendum would have done.”

Source: The Washington Post

Featured image: The Georgetown University campus in Northwest Washington. (Daniel Slim/AFP/Getty Images)