By Antonio Ray Harvey, California Black Media —

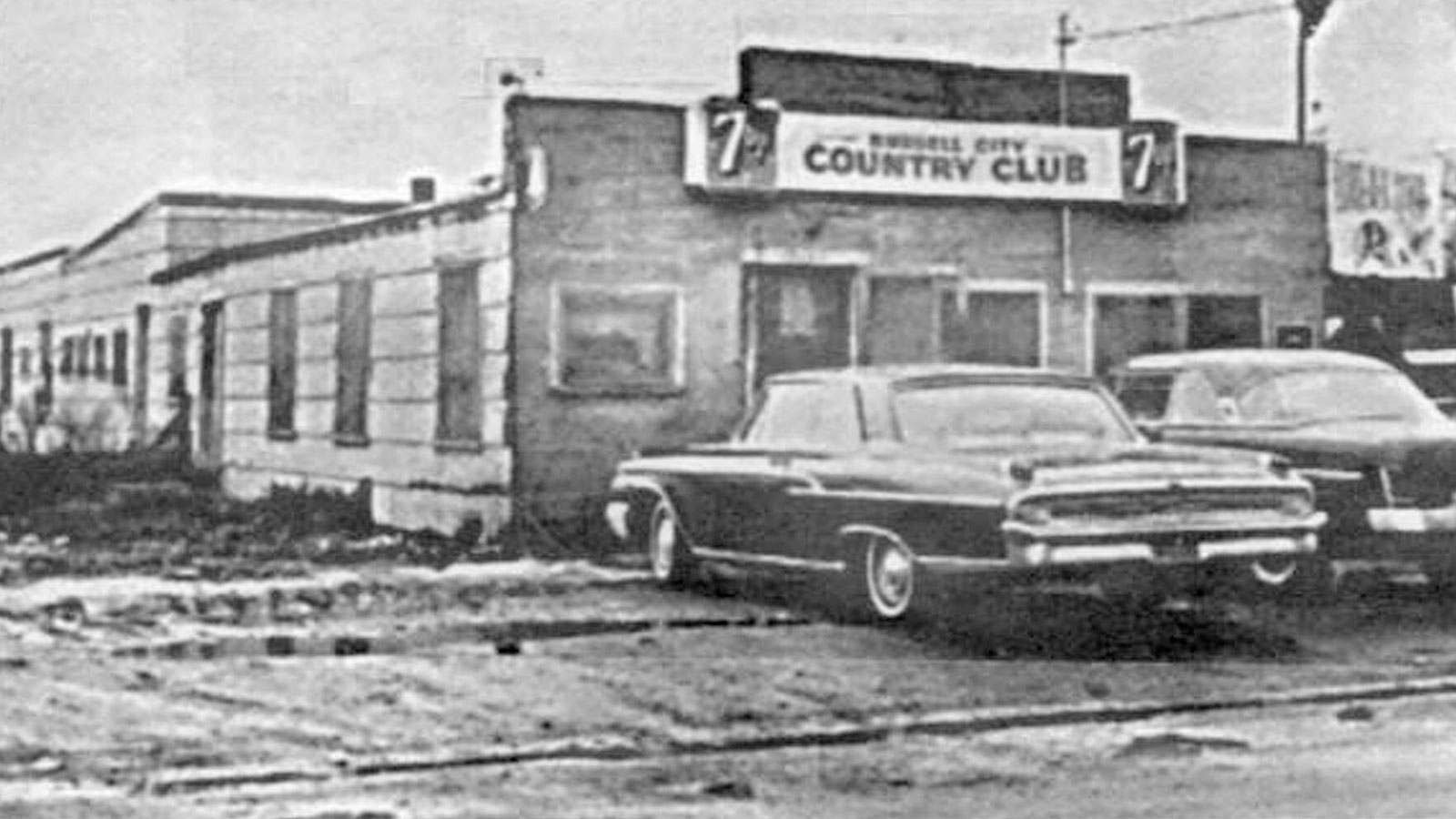

Most people attending a recent community meeting on reparations in the Bay Area had never heard of Russell City, an unincorporated majority Black community in Northern California that local authorities bulldozed in the 1960s, causing the displacement of most of its Black residents.

Many of Russell City’s African American residents had relocated to the Northern California town, located in present-day Hayward, to escape segregation and sharecropping in the South.

Russell City

Marian Johnson and Michael Johnson, sister and brother, testified at the meeting co-hosted by the Coalition for A Just and Equitable California (CJEC) with the support of the California Task Force to Study and Develop Reparations Proposals for African Americans. Both their grandparents and great-grandparents lived in Russell city.

CJEC is a statewide coalition of organizations, fighting for reparations for the descendants of enslaved Black Americans.

The Johnsons explained to the audience what Russell City meant to them and why they are supporting the push for reparations in California.

“Russell City had a population of 1,400 people and 400 homes. It was a ‘redlined community,’ and all the properties were taken by eminent domain,” Marian Johnson said. “In California, a lot of this happened and a lot of people did not know it happened. It’s a secret. Now, it’s coming to light.”

The Coalition for A Just and Equitable California (CJEC) is a statewide coalition of organizations, fighting for reparations for descendants of enslaved Black Americans. (source: facebook.com)

Task Force member Don Tamaki attended the meeting. He said the information shared during the discussion is pertinent to correcting the injustices that prevented Black families from building generational wealth.

“What you are describing is what happened to the Fillmore District, the ‘Harlem of the West,’ in the 1950s, where 20,000 were actually displaced and almost 900 Black businesses were destroyed because of eminent domain,” Tamaki told California Black Media, referring to the historic majority Black San Francisco neighborhood known as the Golden City’s foremost Black cultural and political hub.

Russell City started as a farming community in 1853. It was founded by a Danish immigrant who provided sanctuary to African Americans before and after the Civil War.

As the community grew, it became independent, and “culturally vibrant,” Michael Johnson said. By the 1950s, though, Hayward leaders considered Russell City a “blight” to the surrounding area and sought to rebuild it as an industrial park.

On Jan. 8, 1963, Alameda County and Hayward officials began hearings to discuss the forced removal of Russell City residents. Soon after, authorities wiped out the entire community with bulldozers, and rezoned the land for industrial use.

Russell City started as a farming community in 1853. It was founded by a Danish immigrant who provided sanctuary to African Americans before and after the Civil War. (source: sfgate.com)

Michael Johnson said one of his grandparents moved to Russell City because urban renewal pushed them out of the Fillmore District in San Francisco.

“Ultimately, they moved those Africans, indigenous, and people of color into Russell City because they couldn’t buy homes in Hayward or Oakland. Then, they determined it was a blighted area and forced them out,” said Michael Johnson.

Bruce’s Beach

Since the reparations task force started holding meetings in June 2021, numerous accounts of private and state-backed land grabs targeting African Americans have surfaced. Some of the property was taken from Black landowners through eminent domain in the name of “urban renewal” projects. Others were stolen through fraud, intimidation and violence.

Last year, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill to return Manhattan Beach property to descendants of the Bruce family who owned a beachfront resort in Los Angeles County before it was forcefully taken from them in the early 1920s.

Chris Lodgson, a member of CJEC, said he is asking other Black Californians like the Johnsons to come forward with their stories.

CJEC is one of seven organizations across the state that will hold “listening sessions” involving Black Californians from different backgrounds and regions of the state.

The community partners of the Richmond event were Parable of the Sower Intentional Community Cooperative (PSICC), Richmond Progressive Alliance, and the Bay Area Black Alliance for Peace (BAP).

Members of the National Black Liberation Movement Network (NBLMN) and AfroSocialists also attended.

On September 30, 2021, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill to return Manhattan Beach property known as Bruce’s Beach in Los Angeles to the family’s descendants. (source: gov.ca.gov)

The Richmond testimonies mirrored other accounts that have been shared with the task force. Another Southern California eminent domain case coming to light – and to the attention of the task force — had been obscured for over six decades.

Silas White and the Belmar Triangle

In 1958, Silas White, a Black entrepreneur, had a grand idea to open a recreational venue on Santa Monica Beach called the Ebony Beach Club. White had a vision for entertainment and leisure that would include golf tournaments, talent shows, and fishing trips.

Before White could move ahead with his plans, Santa Monica officials used eminent domain to take his property at 1811 Ocean Avenue. The facility was near a tight-knit community of Black Californians that lived, worked, and attended churches in the Belmar Triangle.

The city of Santa Monica demolished the building in January 1960 after White lost a court battle to keep the property. Subsequently, homes in the vicinity owned by Black people were burned to the ground to build the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium.

In 2021, Hayward City Council voted unanimously to approve a resolution apologizing to African Americans and other people of color for the city’s real estate and banking industries’ “racially disparate impacts and inequities resulting from past City policy and decision-making,” the council said in a statement.

In 1958, Silas White, a Black entrepreneur, had a grand idea to open a recreational venue on Santa Monica Beach called the Ebony Beach Club but before he could implement his vision Santa Monica officials used eminent domain to take his property at 1811 Ocean Avenue. (smconservancy.org)

“The resolution also cites Hayward’s participation in federally sponsored urban renewal initiatives, which frequently resulted in the mass displacement and dislocation without fair compensation of largely Black households, neighborhoods, and entire communities across the country during the 1960s and 1970s,” the council stated.

The Hayward Community Services Commission has drawn up a list of 10 steps the Bay Area City could develop to address past unfairness and complicity in historical racism and social injustices.

The program would also include working with surviving Russell City to determine appropriate restitution.

Michael Johnson said restitution should be reparations.

“There are a number of things we want. No. 1, we want our land back. We have proof that we own the property,” said Michael Johnson, who grew up in East Oakland. “Secondly, we want all the leases turned over to the rightful owners of that land and the taxes collected over 58 years. The other form of reparations, that we see fit is maybe not having a tax on the land for the next 50 years.”

Lodgson said more stories like Russell City will emerge as the listening sessions get underway.

“There is so much work to be done. There is no turning back,” Lodgson said.

The Reparations Task Force next two-day meeting will be held March 30 at 9 a.m. You can participate or observe here.