By Linda J. Bilmes and Cornell William Brooks, The Conversation —

As Americans celebrate Juneteenth, legislation for a commission to study reparations for harms resulting from the enslavement of nearly 4 million people has languished in Congress for more than 30 years.

Though America has yet to begin compensating Black Americans for past and ongoing racial harms, our new research published in the Russell Sage Foundation Journal in June 2024, refutes one of the key arguments against making reparation payments – that they would be too difficult and expensive for the federal government to administer.

We discovered hundreds of cases and analyzed more than 70 programs in which the federal government pays what we term “reparatory compensation” to millions of Americans.

The long history of US compensation

Since the 1930s, the U.S. government has made payments for many types of nonracial harms, including personal injury, illness, disease, financial loss, natural disasters, market failures and social injustices.

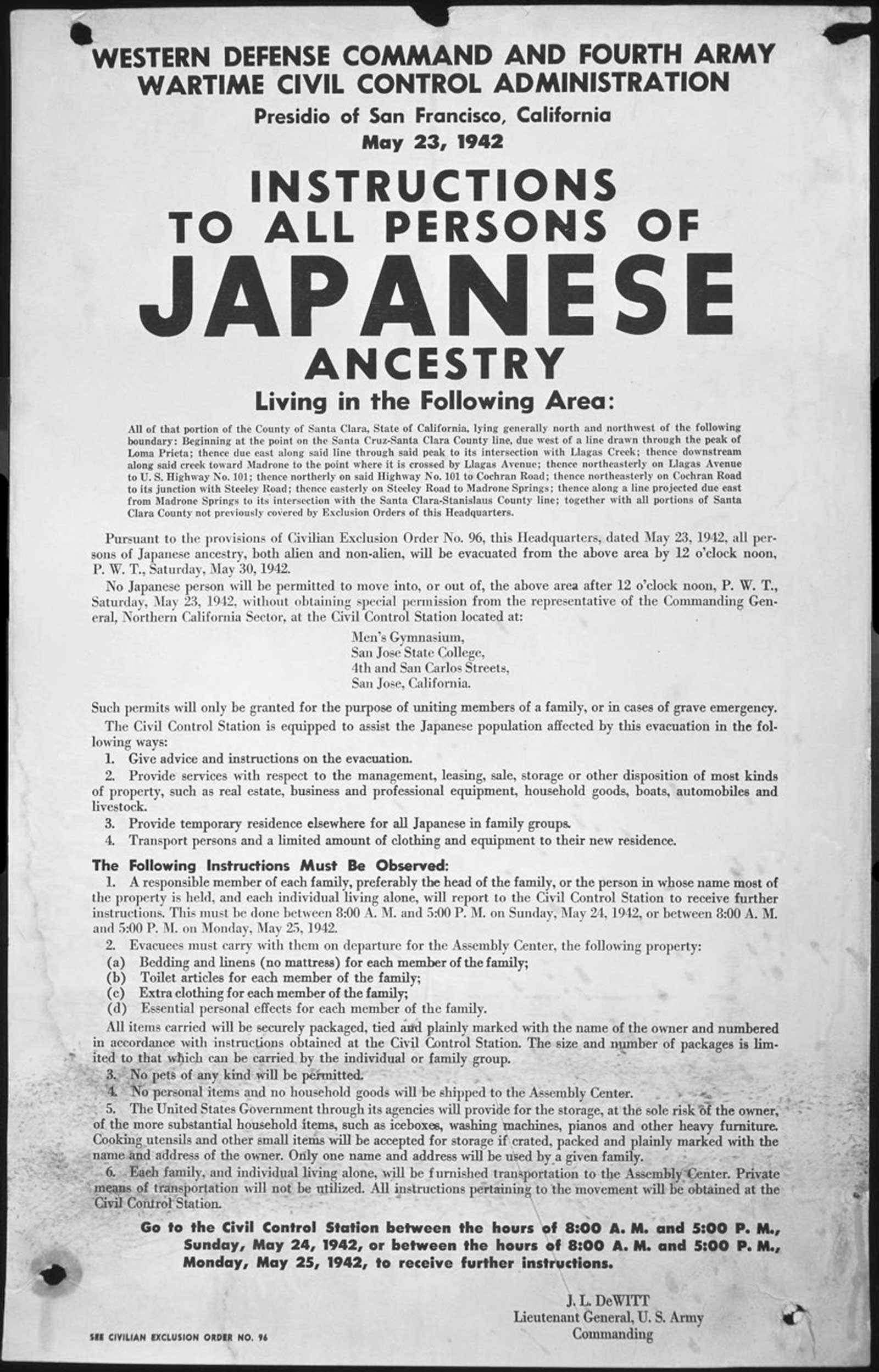

In 1988, for example, the U.S. government paid reparations to Japanese Americans – and in some cases, their descendants – who were forced into internment camps during World War II.

With the authorization of the government, the U.S. military rounded up and incarcerated Japanese Americans shortly after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

In another example, starting in the 1990s, Congress passed a series of laws to compensate people in 12 western states and the Marshall Islands who were exposed to dangerous levels of radiation from the government’s nuclear testing program that occurred in the 1940s and 1950s. Since 1990, these programs have compensated some 135,000 victims and paid out US$28 billion to these victims and to some of their heirs.

America has paid compensation to coal miners who have contracted lung diseases, farmers who have endured crop failures and fishermen facing depleted fish stocks.

The federal government has also paid compensation to victims of terrorism, wrongful convictions and natural disasters.

It also has paid partial restitution to thousands of descendants of Native American tribes, whose tribal land earnings were stolen or mismanaged dating back to the 1880s.

Indeed, the federal government has long attempted to compensate individuals – and in certain cases entire communities – through a combination of restitution, financial benefits and rehabilitation.

These programs cost billions of dollars annually and are funded in a variety of ways, including specific excise taxes, the use of government trust funds and subsidized insurance policies.

We have determined that the diversity, scale and complexity of federal programs and beneficiaries show that reparations are administratively feasible. While only a few of these programs address racial injustice, they all demonstrate the government’s capacity to administer large-scale programs of compensation for those directly and indirectly harmed.

The ongoing harms to Black Americans

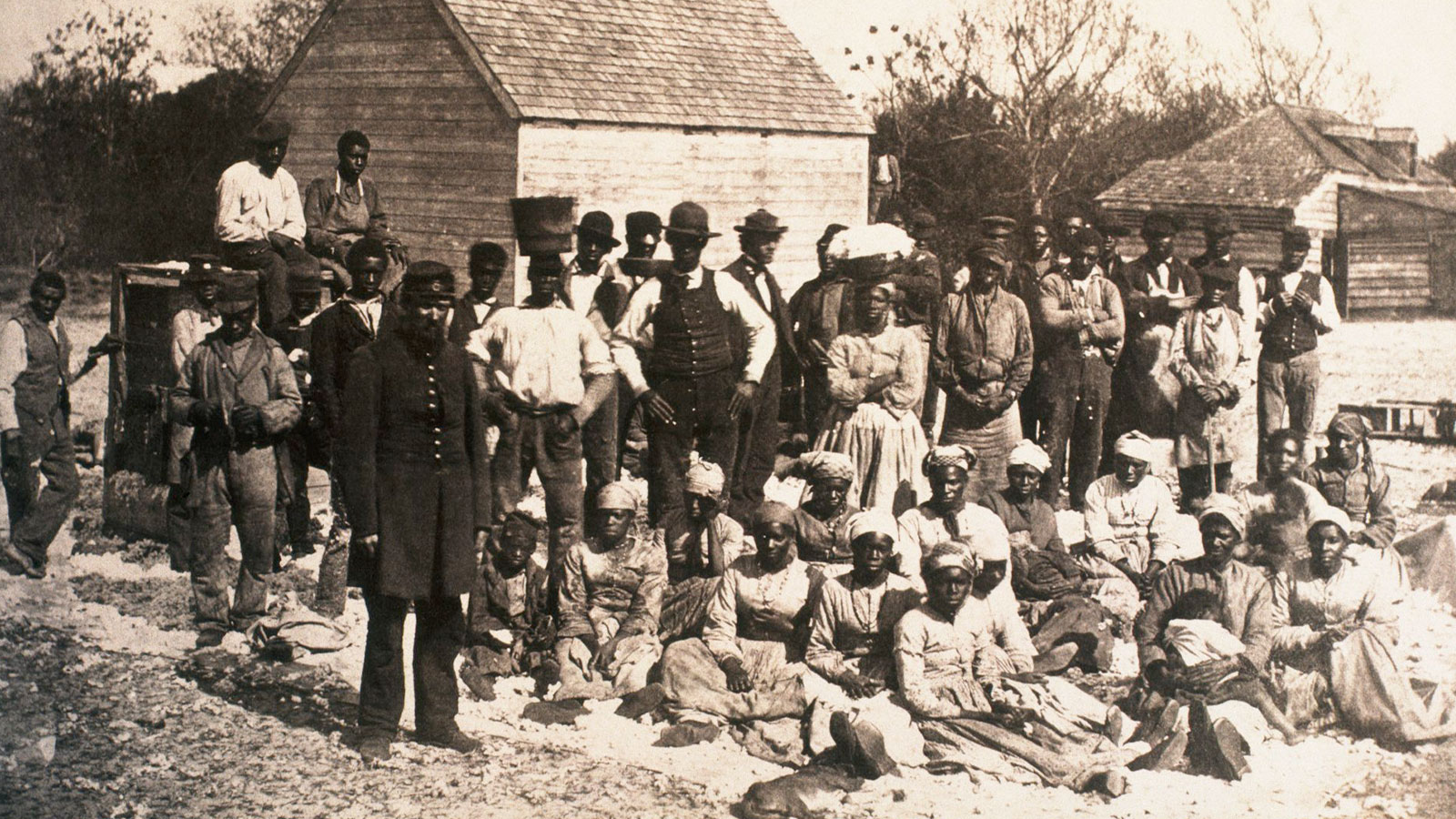

The harms of slavery did not end on June 19, 1865, the day known as Juneteenth when enslaved Black people in Galveston, Texas, finally learned of their freedom – well after the Emancipation Proclamation enacted by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863.

The harms continued during the Jim Crow era of legalized segregation and can be seen in today’s disparate outcomes in health, wealth, housing, employment and education.

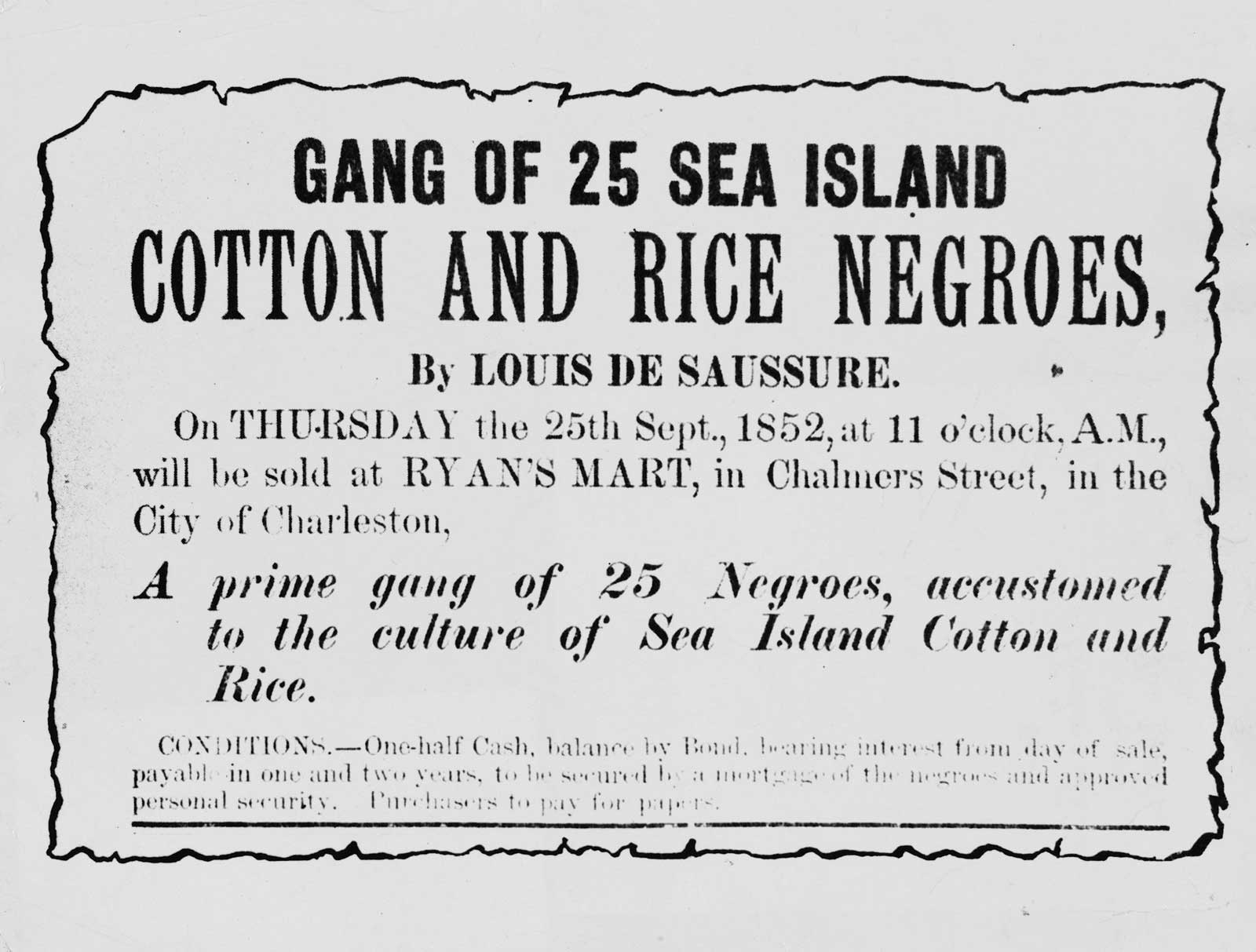

An advertisement details the auction sale of 25 enslaved Black people at Ryan’s Mart in Charleston, S.C., on Sept. 25, 1852. Kean Collection/Archive Photos via Getty Images

Among the most uncompensated victims of racial harm are Black veterans.

After the Civil War, the federal government made a promise to all formerly enslaved people and, in particular, Black veterans: a military pension and reparations in the form of 40 acres and a mule.

The government then reneged on its promise of land, mules or any other restitution – even as it distributed millions of acres of western land to mostly white settlers for free, under the Homestead Act.

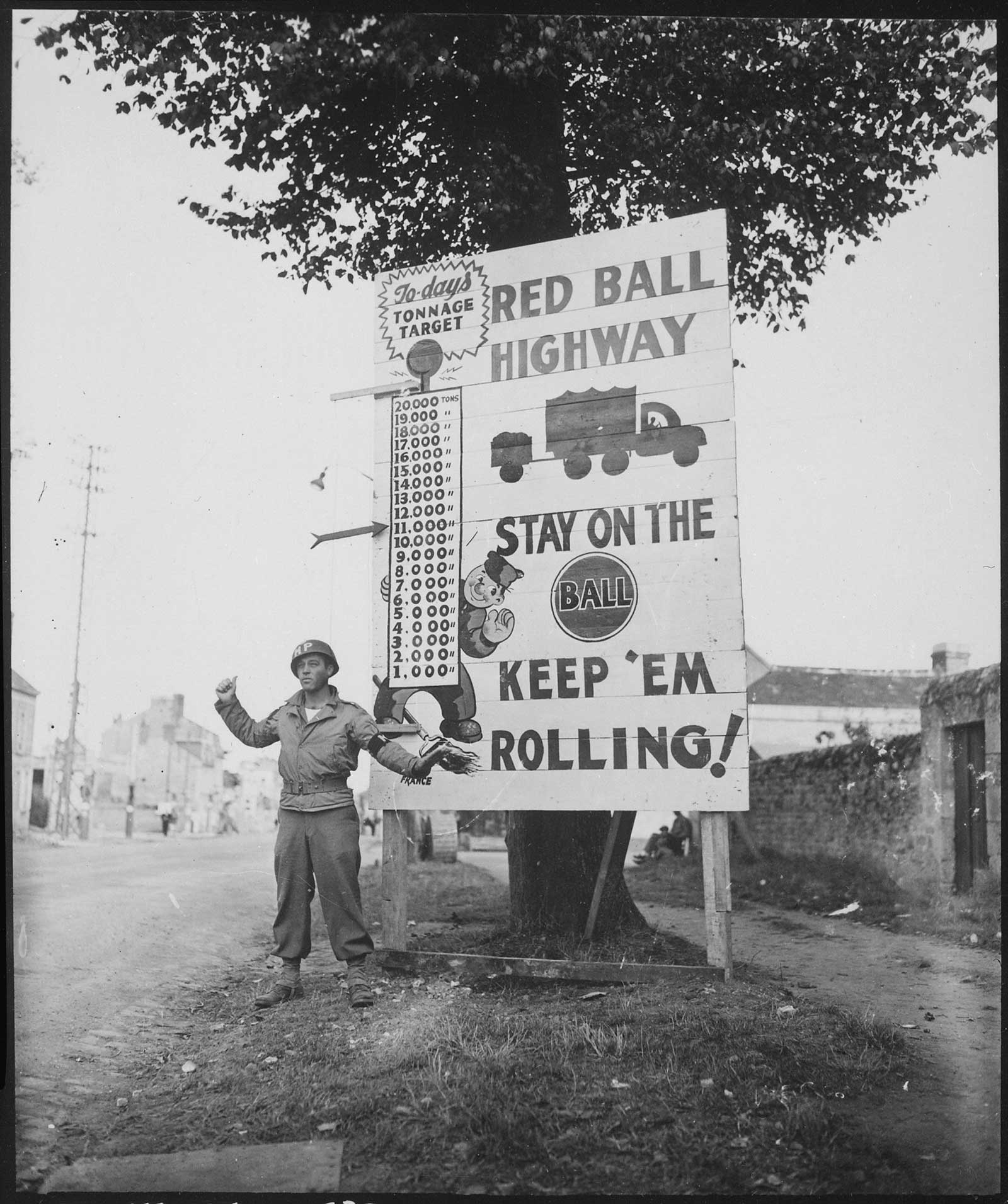

In this Sept. 5, 1944, photograph, Cpl. Charles H. Johnson of the 783rd Military Police Battalion waves on a Red Ball Express convoy near Alenon, France. National Archives

Black men who fought in World War II and the Korean War suffered the same treatment. The 1944 GI Bill enabled millions of white veterans – including many working-class European immigrants – to buy homes and secure qualifications that led to higher-paying professional and trade jobs.

But nearly all Black veterans were denied those benefits.

Taken all together, the harms endured by Black people over several generations have produced a $14 trillion wealth gap between Black and white Americans.

Righting the wrongs of the past

Although a majority of Americans oppose paying reparations for the wrongs of slavery, a 2021 University of Massachusetts/Amherst poll show that 57% of all voters age 18 to 29, and 64% of Democrats, support reparations to the descendants of enslaved men and women.

Moreover, the poll found, a significant percent of those who are opposed to reparations say it’s because they lack confidence in the government’s ability to design a fair program.

Our research into existing compensation proves that the government has the skill and experience to do this.

The question in our view is whether the nation has the will to examine the long-enduring harms from slavery – and to begin to repair those wrongs.

Source: The Conversation

Linda J. Bilmes: Daniel Patrick Moynihan Senior Lecturer in Public Policy and Public Finance, Harvard Kennedy School

Cornell William Brooks: Professor of the Practice of Public Leadership and Social Justice, Harvard Kennedy School