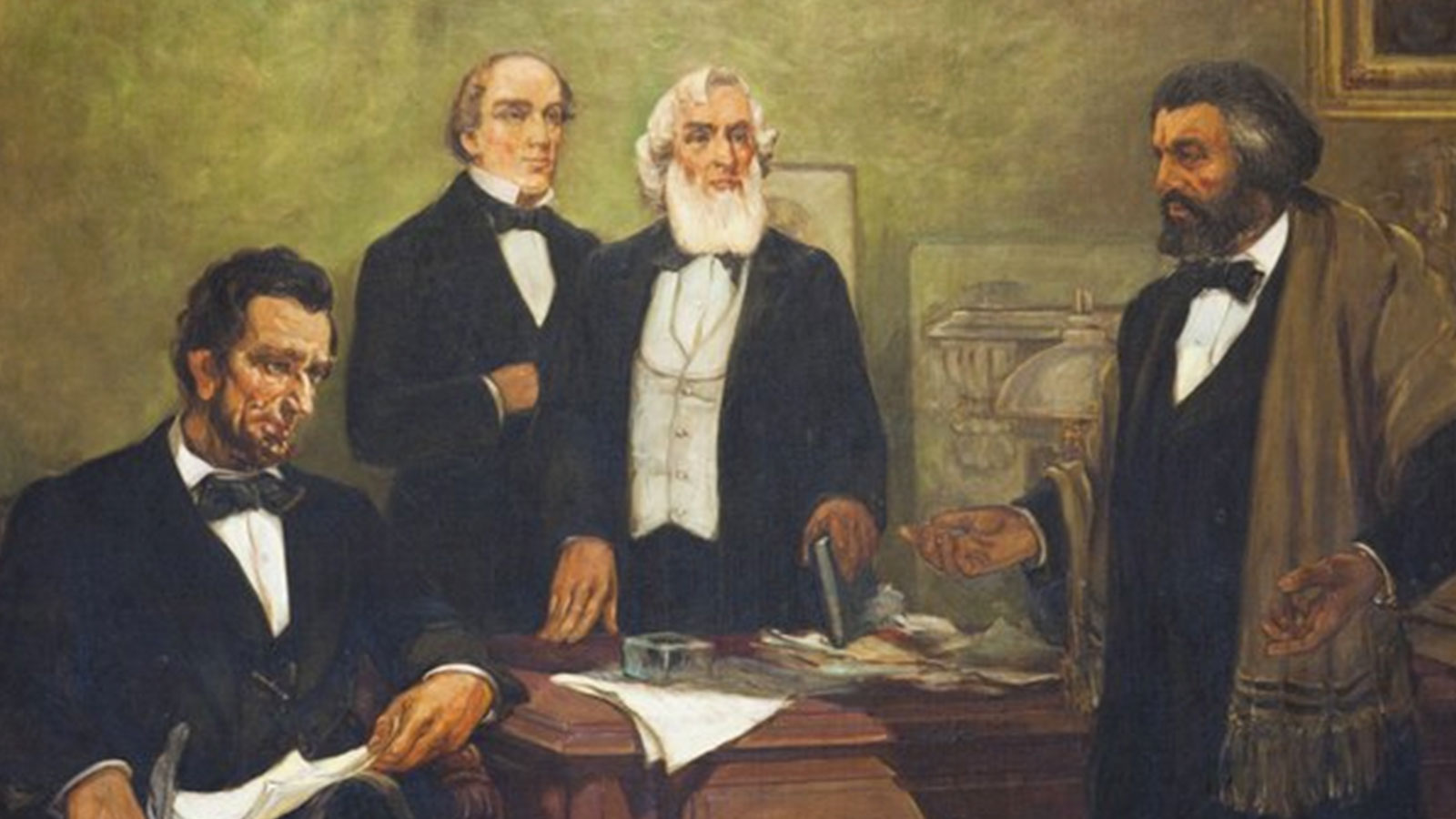

Six weeks after Lincoln’s death, Frederick Douglass described him as “emphatically the black man’s president, the first chief executive “to show any respect for the rights of a black man, or to acknowledge that he had any rights the white man ought to respect,” the first one to rise “above the prejudices of his times and country.” Lincoln treated each African American “not as a patron, but as an equal.” Speaking of his own experience in 1864 when the president summoned him to the White House to discuss public affairs, Douglass concluded: “In daring to admit, nay in daring to invite a Negro to an audience at the White House, Mr. Lincoln did that which he knew would be offensive to the crowd and excite their ribaldry. It was saying to the country, I am President of the black people as well as the white, and I mean to respect their rights and feelings as men and as citizens.” Echoing Douglass, historian David Reynolds has recently deemed the sixteenth president a “radical antiracist” and a “leftist abolitionist who loathed racism.”

In The Black Man’s President: Abraham Lincoln, African Americans, and the Pursuit of Racial Equality, I attempt to illustrate Lincoln’s racial egalitarianism by describing his interactions with African Americans, both during his presidency and his Illinois years. As Reynolds recently observed, it is only by studying Lincoln’s “personal interchange with black people” can “we see the complete falsity of the charges of innate racism that some have levelled at him over the years.”

Lincoln’s unfailing cordiality to African Americans in general, both in Springfield and Washington; his willingness to meet with them in the White House; to honor their requests; to invite them to consult on public policy; to treat them with respect and kindness whether they were kitchen servants or leaders of the Black community; to invite them to attend receptions and tea; to sing and pray with them on their turf; to authorize them to hold events on the White House grounds—all those manifestations of an egalitarian spirit fully justified the tribute paid to him by Frederick Douglass and other African Americans who met with him. Among them was Sojourner Truth, who called at the White House in 1864 and shortly thereafter wrote: “I never was treated by any one with more kindness and cordiality than were shown to me by that great and good man.”

Black workers in the Executive Mansion reacted similarly. Elizabeth Keckly, a former slave who became the First Lady’s dressmaker and confidante, observed Lincoln closely throughout the Civil War and told a journalist: “I loved him for his kind manner towards me.” He “was as kind and considerate in his treatment of me as he was of any of the white people about the white house.” Other African Americans with whom Lincoln interacted included Peter Brown, a waiter whose young son spent much time at the Executive Mansion during the Civil War and remembered that Lincoln “was kind to everybody” and “sympathized with us colored folks, and we loved him.” The daughter of William Slade, the African American head butler at the Executive Mansion, reported that the president “never treated [the White House employees] as servants, but always was polite and requested service, rather than demand it of them.”

Many Black people visited the Lincoln White House. As Clarence Lusane, a political scientist at Howard University, noted: “political access to the White House had been extended to the black community for the first time in U.S. history” during Lincoln’s presidency, and that included not only prominent people like Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth, but also “many lesser known activists and ordinary African Americans” who “met with him there as well. The significance of these encounters cannot be overstated.” The “multiracial space that Lincoln opened would be a critical new element in the ongoing struggle for black freedom and equality.”

Those callers included Black Washingtonians who attended receptions at the Executive Mansion, much to the consternation of Democrats, who denounced the president for thereby promoting social equality and miscegenation. Other African Americans came to ask favors, to urge emancipation and the recruitment of Black troops, to lobby on behalf of colonization abroad, to express thanks, and on some notable occasions to press for Black suffrage rights. Arguably the most influential such meeting occurred in March 1864, when two African Americans from New Orleans presented a petition signed by a thousand Black residents of the Crescent City appealing for the right to vote. Lincoln received them cordially, expressed sympathy for their cause, but noted that states, not the federal government, determined suffrage qualifications. A few days later, the president acted on their request by writing to the newly elected governor of Louisiana, suggesting that it would be desirable if the state constitutional convention that was scheduled to meet soon would enfranchise at least some black men, like those serving in the army and the very intelligent, by which he evidently meant literate. The governor used that letter to effect, and the convention voted to authorize the legislature, if it saw fit, to enfranchise some Black men. That helped pave the way for the eventual enfranchisement of Black Louisianans in 1868.

On April 11, 1865, thirteen months after receiving the New Orleans petition, Lincoln for the first time publicly endorsed Black suffrage. He told a huge crowd gathered at the White House that he favored extending voting rights to Black soldiers and sailors as well as the very intelligent. Upon hearing that speech, John Wilkes Booth turned to his companions and said: “That means [n-word] citizenship. Now by God I’ll put him through!” He added: “That is the last speech he will ever make.” Three days later he carried out his threat by assassinating the president. Thus Lincoln should be regarded as a martyr to Black civil rights, as much as Martin Luther King, Medgar Evers, Viola Liuzo, James Cheney, Micky Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and the other champions of that cause who were murdered during the civil rights movement of the 20th century.

Source: HNN

Michael Burlingame holds the Chancellor Naomi B. Lynn Distinguished Chair in Lincoln Studies at the University of Illinois Springfield. He is the author or editor of several books about Lincoln, including An American Marriage; Lincoln Observed; The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln; and the two-volume critical masterpiece Abraham Lincoln: A Life. His most recent book, The Black Man’s President: Abraham Lincoln, African Americans, and the Pursuit of Racial Equality, was published on November 2.