These letters from Black Americans to the people who once controlled their lives show a desire for freedom and a desperate longing to be reunited with their families.

By Gillian Brockell, The Washington Post —

Some are exquisite condemnations from learned and accomplished men who escaped their enslavement. Some are brief queries, shots in the dark, dictated by illiterate women. One is brilliant sarcasm, humorously calculating and requesting back wages.

All of these letters from Black Americans to the people who once controlled their lives show a desire for freedom and a desperate longing to be reunited with their families.

Three of these five letters were written by formerly enslaved people directly to their onetime enslavers. One was addressed to President Abraham Lincoln, who had the power to emancipate its author and had so far withheld it. One was written by a still-enslaved woman desperately searching for her daughter.

Spelling has been standardized and paragraph breaks added for readability.

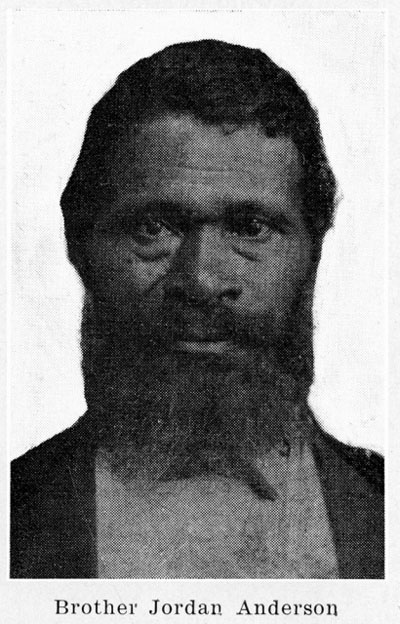

“Send us our wages”: Jourdon Anderson, 1865

Jourdon Anderson and his family were freed by Union troops during the Civil War and left Tennessee for Ohio. A few months after the war ended, Anderson’s former enslaver wrote to him, asking him to return to the plantation, where the harvest was about to come in, and promising a wage and freedom. Anderson dictated his reply to his abolitionist employer, who was so impressed with its wit he had it published in the newspaper.

Dayton, Ohio, August 7, 1865

To my old Master, Colonel P. H. Anderson, Big Spring, Tennessee

Sir:

I got your letter, and was glad to find that you had not forgotten Jourdon, and that you wanted me to come back and live with you again, promising to do better for me than anybody else can. I have often felt uneasy about you. I thought the Yankees would have hung you long before this, for harboring Rebs they found at your house. I suppose they never heard about your going to Colonel Martin’s to kill the Union soldier that was left by his company in their stable.

Although you shot at me twice before I left you, I did not want to hear of your being hurt, and am glad you are still living. It would do me good to go back to the dear old home again, and see Miss Mary and Miss Martha and Allen, Esther, Green, and Lee. Give my love to them all, and tell them I hope we will meet in the better world, if not in this. I would have gone back to see you all when I was working in the Nashville Hospital, but one of the neighbors told me that Henry intended to shoot me if he ever got a chance.

I want to know particularly what “the good chance” is you propose to give me. I am doing tolerably well here. I get $25 a month, with victuals and clothing; have a comfortable home for Mandy (the folks call her Mrs. Anderson), and the children, Milly, Jane, and Grundy, go to school and are learning well. The teacher says Grundy has a head for a preacher. They go to Sunday school, and Mandy and me attend church regularly. We are kindly treated. Sometimes we overhear others saying, “Them colored people were slaves” down in Tennessee. The children feel hurt when they hear such remarks; but I tell them it was no disgrace in Tennessee to belong to Colonel Anderson. Many darkeys would have been proud, as I used to be, to call you master.

Now if you will write and say what wages you will give me, I will be better able to decide whether it would be to my advantage to move back again.

As to my freedom, which you say I can have, there is nothing to be gained on that score, as I got my free papers in 1864 from the Provost-Marshal-General of the Department of Nashville. Mandy says she would be afraid to go back without some proof that you were disposed to treat us justly and kindly; and we have concluded to test your sincerity by asking you to send us our wages for the time we served you. This will make us forget and forgive old scores, and rely on your justice and friendship in the future.

I served you faithfully for thirty-two years, and Mandy twenty years. At $25 a month for me, and $2 a week for Mandy, our earnings would amount to $11,680. Add to this the interest for the time our wages have been kept back, and deduct what you paid for our clothing, and three doctor’s visits to me, and pulling a tooth for Mandy, and the balance will show what we are in justice entitled to. Please send the money by Adams Express, in care of V. Winters, Esq., Dayton, Ohio.

If you fail to pay us for faithful labors in the past, we can have little faith in your promises in the future. We trust the good Maker has opened your eyes to the wrongs which you and your fathers have done to me and my fathers, in making us toil for you for generations without recompense. Here I draw my wages every Saturday night; but in Tennessee there was never any pay-day for the negroes any more than for the horses and cows. Surely there will be a day of reckoning for those who defraud the laborer of his hire.

In answering this letter, please state if there would be any safety for my Milly and Jane, who are now grown up, and both good-looking girls. You know how it was with poor Matilda and Catherine. I would rather stay here and starve and die, if it come to that, than have my girls brought to shame by the violence and wickedness of their young masters.

You will also please state if there has been any schools opened for the colored children in your neighborhood. The great desire of my life now is to give my children an education, and have them form virtuous habits.

From your old servant, Jourdon Anderson

P.S.— Say howdy to George Carter, and thank him for taking the pistol from you when you were shooting at me.

Anderson’s former enslaver was forced to sell his plantation and died a few years later at 44. Anderson lived a long life, had 11 children with his wife and became a sexton in his church.

“It is my Desire to be free”: Annie Davis (to Abraham Lincoln), 1864

Lincoln was never a slaveholder, but as president during the Civil War, he held the fate and freedom of millions of Black Americans in his hands. As such, he received hundreds of letters from Black Americans, both free and enslaved, many of which are collected in a new book. When Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation, he did not free enslaved people in slave states that remained in the Union, like Maryland, where Annie Davis was held.

Belair, Aug. 25th, 1864

Mr. President,

It is my Desire to be free. To go to see my people on the Eastern Shore. My mistress won’t let me.

You will please let me know if we are free and what I can do. I write to you for advice. Please send me word this week, or as soon as possible, and obliged.

Annie Davis

Belair, Harford County, MD.

There is no evidence Lincoln responded. However, the state of Maryland ended slavery months later, a move the president had urged.

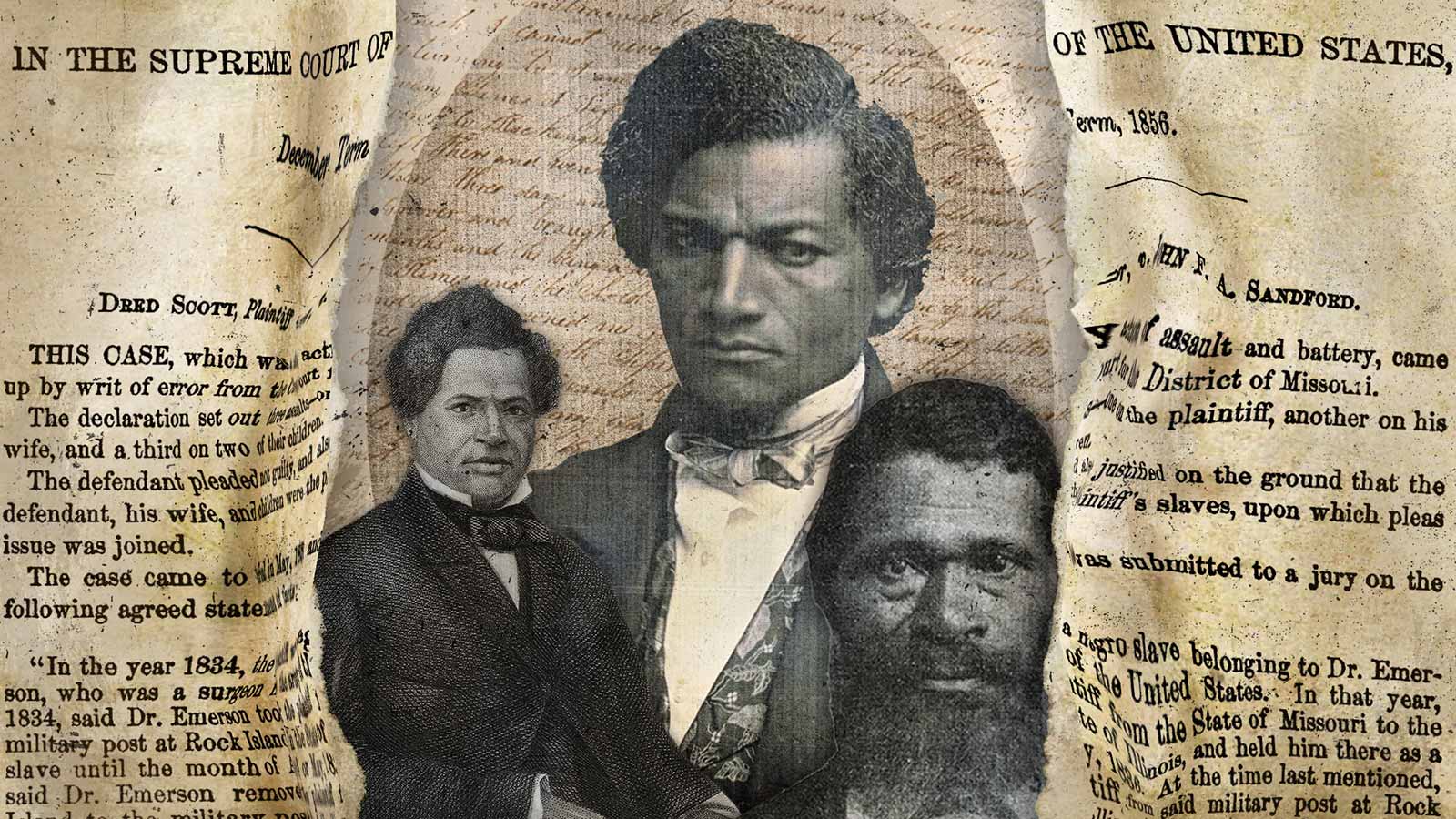

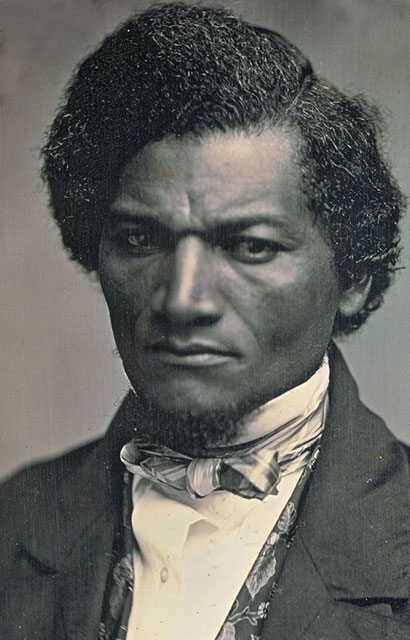

Frederick Douglass circa 1847-1852, about the time he wrote a letter to his former enslaver, Thomas Auld. (Samuel J. Miller/Art Institute of Chicago)

“I took nothing but what belonged to me”: Frederick Douglass, 1848

Ten years after escaping slavery, famed abolitionist orator and activist Frederick Douglass published an open letter to his former enslaver, Thomas Auld, in the abolitionist newspaper Douglass founded, the North Star. This is an excerpt of the full 3,400-word letter.

I have often thought I should like to explain to you the grounds upon which I have justified myself in running away from you. I am almost ashamed to do so now, for by this time you may have discovered them yourself. I will, however, glance at them.

When yet but a child about six years old, I imbibed the determination to run away. The very first mental effort that I now remember on my part, was an attempt to solve the mystery — why am I a slave? and with this question my youthful mind was troubled for many days, pressing upon me more heavily at times than others. When I saw the slave-driver whip a slave-woman, cut the blood out of her neck, and heard her piteous cries, I went away into the corner of the fence, wept and pondered over the mystery.

I had, through some medium, I know not what, got some idea of God, the Creator of all mankind, the black and the white, and that he had made the blacks to serve the whites as slaves. How he could do this and be good, I could not tell. I was not satisfied with this theory, which made God responsible for slavery, for it pained me greatly, and I have wept over it long and often.

At one time, your first wife, Mrs. Lucretia, heard me sighing and saw me shedding tears, and asked of me the matter, but I was afraid to tell her. I was puzzled with this question, till one night while sitting in the kitchen, I heard some of the old slaves talking of their parents having been stolen from Africa by white men and were sold here as slaves. The whole mystery was solved at once.

Very soon after this, my Aunt Jinny and Uncle Noah ran away, and the great noise made about it by your father-in-law made me, for the first time, acquainted with the fact that there were free states as well as slave states. From that time, I resolved that I would someday run away.

The morality of the act I dispose of as follows: I am myself; you are yourself; we are two distinct persons, equal persons. What you are, I am. You are a man, and so am I. God created both, and made us separate beings. I am not by nature bond to you, or you to me. Nature does not make your existence depend upon me, or mine to depend upon yours. I cannot walk upon your legs, or you upon mine. I cannot breathe for you, or you for me; I must breathe for myself, and you for yourself. We are distinct persons, and are each equally provided with faculties necessary to our individual existence.

In leaving you, I took nothing but what belonged to me, and in no way lessened your means for obtaining an honest living. Your faculties remained yours, and mine became useful to their rightful owner. I therefore see no wrong in any part of the transaction. It is true, I went off secretly; but that was more your fault than mine. Had I let you into the secret, you would have defeated the enterprise entirely; but for this, I should have been really glad to have made you acquainted with my intentions to leave.

You may perhaps want to know how I like my present condition. I am free to say, I greatly prefer it to that which I occupied in Maryland. I am, however, by no means prejudiced against the state as such. Its geography, climate, fertility, and products are such as to make it a very desirable abode for any man; and but for the existence of slavery there, it is not impossible that I might again take up my abode in that state. It is not that I love Maryland less, but freedom more.

Since I left you, I have had a rich experience. I have occupied stations which I never dreamed of when a slave. Three out of the ten years since I left you, I spent as a common laborer on the wharves of New Bedford, Massachusetts. It was there I earned my first free dollar. It was mine. I could spend it as I pleased. I could buy hams or herring with it, without asking any odds of anybody. That was a precious dollar to me. You remember when I used to make seven, or eight, or even nine dollars a week in Baltimore, you would take every cent of it from me every Saturday night, saying that I belonged to you, and my earnings also. I never liked this conduct on your part — to say the best, I thought it a little mean. I would not have served you so. But let that pass.

I have an industrious and neat companion, and four dear children — the oldest a girl of nine years, and three fine boys, the oldest eight, the next six, and the youngest four years old. The three oldest are now going regularly to school; two can read and write, and the other can spell, with tolerable correctness, words of two syllables. Dear fellows! they are all in comfortable beds, and are sound asleep, perfectly secure under my own roof. There are no slaveholders here to rend my heart by snatching them from my arms, or blast a mother’s dearest hopes by tearing them from her bosom. These dear children are ours — not to work up into rice, sugar, and tobacco, but to watch over, regard, and protect, and to rear them up in the nurture and admonition of the gospel — to train them up in the paths of wisdom and virtue, and, as far as we can, to make them useful to the world and to themselves.

Oh! sir, a slaveholder never appears to me so completely an agent of hell, as when I think of and look upon my dear children. It is then that my feelings rise above my control. I meant to have said more with respect to my own prosperity and happiness, but thoughts and feelings which this recital has quickened, unfits me to proceed further in that direction. The grim horrors of slavery rise in all their ghastly terror before me; the wails of millions pierce my heart and chill my blood.

I remember the chain, the gag, the bloody whip; the death-like gloom overshadowing the broken spirit of the fettered bondman; the appalling liability of his being torn away from wife and children, and sold like a beast in the market. Say not that this is a picture of fancy. You well know that I wear stripes on my back, inflicted by your direction; and that you, while we were brothers in the same church, caused this right hand, with which I am now penning this letter, to be closely tied to my left, and my person dragged, at the pistol’s mouth, fifteen miles, from the Bay Side to Easton, to be sold like a beast in the market, for the alleged crime of intending to escape from your possession. All this, and more, you remember, and know to be perfectly true, not only of yourself, but of nearly all of the slaveholders around you.

At this moment, you are probably the guilty holder of at least three of my own dear sisters, and my only brother, in bondage. These you regard as your property. They are recorded on your ledger, or perhaps have been sold to human flesh-mongers, with a view to filling your own ever-hungry purse. Sir, I desire to know how and where these dear sisters are. Have you sold them? or are they still in your possession? What has become of them? are they living or dead? And my dear old grandmother, whom you turned out like an old horse to die in the woods — is she still alive? Write and let me know all about them.

If my grandmother be still alive, she is of no service to you, for by this time she must be nearly eighty years old — too old to be cared for by one to whom she has ceased to be of service; send her to me at Rochester, or bring her to Philadelphia, and it shall be the crowning happiness of my life to take care of her in her old age. Oh! she was to me a mother and a father, so far as hard toil for my comfort could make her such. Send me my grandmother! that I may watch over and take care of her in her old age. And my sisters — let me know all about them. I would write to them, and learn all I want to know of them, without disturbing you in any way, but that, through your unrighteous conduct, they have been entirely deprived of the power to read and write. You have kept them in utter ignorance, and have therefore robbed them of the sweet enjoyments of writing or receiving letters from absent friends and relatives.

Your wickedness and cruelty, committed in this respect on your fellow creatures, are greater than all the stripes you have laid upon my back or theirs. It is an outrage upon the soul, a war upon the immortal spirit, and one for which you must give account at the bar of our common Father and Creator. The responsibility which you have assumed in this regard is truly awful, and how you could stagger under it these many years is marvelous. Your mind must have become darkened, your heart hardened, your conscience seared and petrified, or you would have long since thrown off the accursed load, and sought relief at the hands of a sin-forgiving God.

I will now bring this letter to a close; you shall hear from me again unless you let me hear from you. I intend to make use of you as a weapon with which to assail the system of slavery — as a means of concentrating public attention on the system, and deepening the horror of trafficking in the souls and bodies of men. I shall make use of you as a means of exposing the character of the American church and clergy — and as a means of bringing this guilty nation, with yourself, to repentance. In doing this, I entertain no malice toward you personally. There is no roof under which you would be more safe than mine, and there is nothing in my house which you might need for your comfort, which I would not readily grant. Indeed, I should esteem it a privilege to set you an example as to how mankind ought to treat each other.

I am your fellow man, but not your slave.

Douglass met with Auld in 1877. They mostly spoke warmly about family members — Auld’s wife and Douglass’s beloved grandmother — and Auld told Douglass he was right to have escaped bondage.

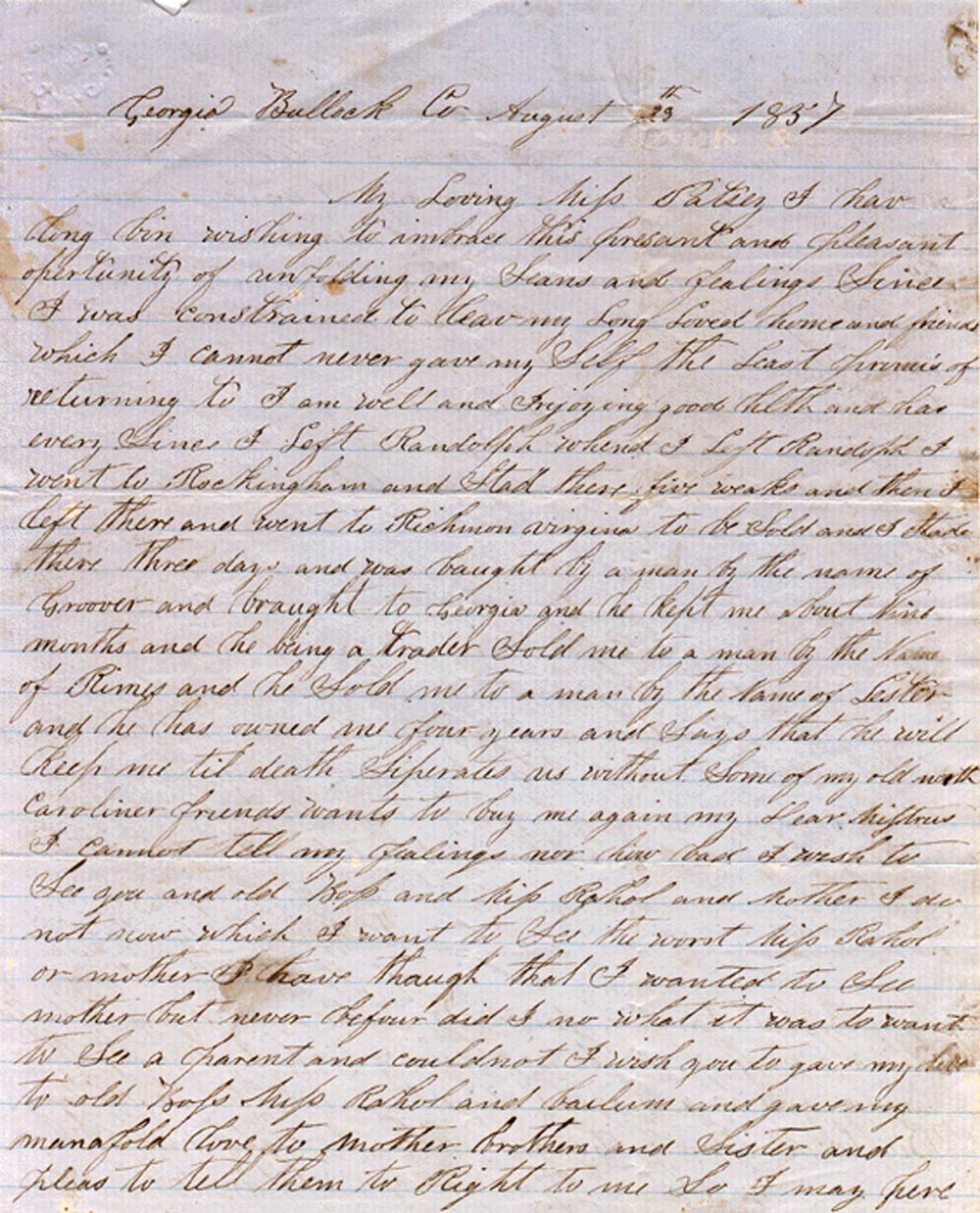

A letter from Vilet Lester to her former enslaver, written in 1857. (David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University)

“What has Ever become of my Precious little girl?”: Vilet Lester, 1857

Nothing is known of Vilet Lester and the fate of her daughter other than what appears in this letter, which she likely dictated to her enslaver and addressed to Patsey Patterson, who may have been the adult daughter of Lester’s former enslaver. It was found in the papers of Patterson’s relatives and is housed at Duke University.

Georgia, Bullock Co., August 29th, 1857

My Loving Miss Patsey,

I have long been wishing to embrace this present and pleasant opportunity of unfolding my [word unclear] and feelings, since I was constrained to leave my Long Loved home and friends, which I cannot never give myself the Least promise of returning to. I am well andEnjoying good health and ha[ve] ever Since I Left Randolph.

When’d I left Randolph, I went to Rockingham and Stayed there five weeks, and then I left there and went to Richmond, Virginia, to be Sold. And I Stayed there three days and was bought by a man by the name of Groover and brought to Georgia, and he kept me about Nine months. And he, being a trader, Sold me to a man by the name of Rimes. And he Sold me to a man by the name of Lester, and he has owned me four years and Says that he will keep me until death Separates us, [unless] Some of my old North Carolina friends wants to buy me again.

My Dear Mistress, I cannot tell my feelings, nor how bad I wish to See you, and old Boss and Miss Rahol and Mother. I do not know which I want to See the worst, Miss Rahol or mother. I have thought that I wanted to See mother, but never before did I know what it was to want to See a parent and could not.

I wish you to give my love to old Boss, Miss Rahol and Bailum, and give my manifold love to mother, brothers and sister, and please to tell them to Write to me, So I may hear from them, if I cannot See them.

And also, I wish you to write to me and write me all the news. I do want to know whether old Boss is Still Living or not, and all the rest of them, and I want to know whether Bailum is married or not. I wish to know what has Ever become of my Precious little girl. I left her in Goldsborough with Mr. Walker, and I have not heard from her Since. And Walker Said that he was going to Carry her to Rockingham and give her to his Sister, and I want to know whether he did or not, as I do wish to See her very much.

And Boss Says he wishes to know whether he [Walker] will Sell her or not, and the least that can buy her. And that he wishes an answer as Soon as he can get one, as I wish him to buy her, and my Boss, being a man of Reason and feeling, wishes to grant my troubled breast that much gratification and wishes to know whether he will Sell her now.

So I must come to a close by Escribing myself your long-loved and well-wishing play mate, as a Servant until death,

Vilet Lester of Georgia to Miss Patsey Patterson of North Carolina

My Boss’s Name is James B. Lester, and if you Should think enough of me to write me, which I do beg the favor of you as a Servant, direct your letter to Millray, Bullock County, Georgia. Please do write me, So fare you well, in love.

Illustration of Jermain Wesley Loguen, a formerly enslaved man who was active in the Underground Railroad. (Onondaga Historical Association)

“Wretched Woman!”: Rev. Jermain Wesley Loguen, 1860

Rev. Jermain Wesley Loguen was born “Jarm Logue” in Tennessee in 1813. His enslaver, Mannasseth Logue, was also his biological father. Twenty-six years after his Christmas escape, Loguen was a renowned minister in Syracuse, N.Y., his home a hub on the Underground Railroad. In February 1860, Logue’s wife wrote to him, giving him a brief update on his family and blaming him for her financial problems. She insisted he return or send her $1,000, or else she would sell him to someone who, because of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, could come to Syracuse and legally kidnap him. This is his reply to her.

Syracuse, N.Y., March 28, 1860

MRS. SARAH LOGUE:—

Yours of the 20th of February is duly received, and I thank you for it. It is a long time since I heard from my poor old mother, and I am glad to know she is yet alive, and, as you say, “as well as common.” What that means I don’t know. I wish you had said more about her.

You are a woman; but had you a woman’s heart you could never have insulted a brother by telling him you sold his only remaining brother and sister, because he put himself beyond your power to convert him into money.

You sold my brother and sister, ABE and ANN, and 12 acres of land, you say, because I ran away. Now you have the unutterable meanness to ask me to return and be your miserable chattel, or in lieu thereof send you $1000 to enable you to redeem the land, but not to redeem my poor brother and sister! If I were to send you money it would be to get my brother and sister, and not that you should get land.

You say you are a cripple, and doubtless you say it to stir my pity, for you know I was susceptible in that direction. I do pity you from the bottom of my heart. Nevertheless I am indignant beyond the power of words to express, that you should be so sunken and cruel as to tear the hearts I love so much all in pieces; that you should be willing to impale and crucify us out of all compassion for your poor foot or leg.

Wretched woman! Be it known to you that I value my freedom, to say nothing of my mother, brothers and sisters, more than your whole body; more, indeed, than my own life; more than all the lives of all the slaveholders and tyrants under Heaven.

You say you have offers to buy me, and that you shall sell me if I do not send you $1000, and in the same breath and almost in the same sentence, you say, “you know we raised you as we did our own children.” Woman, did you raise your own children for the market? Did you raise them for the whipping-post? Did you raise them to be driven off in a coffle in chains? Where are my poor bleeding brothers and sisters? Can you tell? Who was it that sent them off into sugar and cotton fields, to be kicked, and cuffed, and whipped, and to groan and die; and where no kin can hear their groans, or attend and sympathize at their dying bed, or follow in their funeral?

Wretched woman! Do you say you did not do it? Then I reply, your husband did, and you approved the deed — and the very letter you sent me shows that your heart approves it all. Shame on you.

But, by the way, where is your husband? You don’t speak of him. I infer, therefore, that he is dead; that he has gone to his great account, with all his sins against my poor family upon his head. Poor man! gone to meet the spirits of my poor, outraged and murdered people, in a world where Liberty and Justice are MASTERS.

But you say I am a thief, because I took the old mare along with me. Have you got to learn that I had a better right to the old mare, as you call her, than MANNASSETH LOGUE had to me? Is it a greater sin for me to steal his horse, than it was for him to rob my mother’s cradle and steal me? If he and you infer that I forfeit all my rights to you, shall not I infer that you forfeit all your rights to me? Have you got to learn that human rights are mutual and reciprocal, and if you take my liberty and life, you forfeit your own liberty and life? Before God and High Heaven, is there a law for one man which is not a law for every other man?

If you or any other speculator on my body and rights, wish to know how I regard my rights, they need but come here and lay their hands on me to enslave me. Did you think to terrify me by presenting the alternative to give my money to you, or give my body to Slavery? Then let me say to you, that I meet the proposition with unutterable scorn and contempt. The proposition is an outrage and an insult. I will not budge one hair’s breadth. I will not breathe a shorter breath, even to save me from your persecutions. I stand among a free people, who, I thank God, sympathize with my rights, and the rights of mankind; and if your emissaries and venders come here to re-enslave me, and escape the unshrinking vigor of my own right arm, I trust my strong and brave friends, in this City and State, will be my rescuers and avengers.

Yours, &c., J.W. Loguen

Source: The Washington Post