For some Americans, history isn’t the story of what actually happened; it’s the story they want to believe.

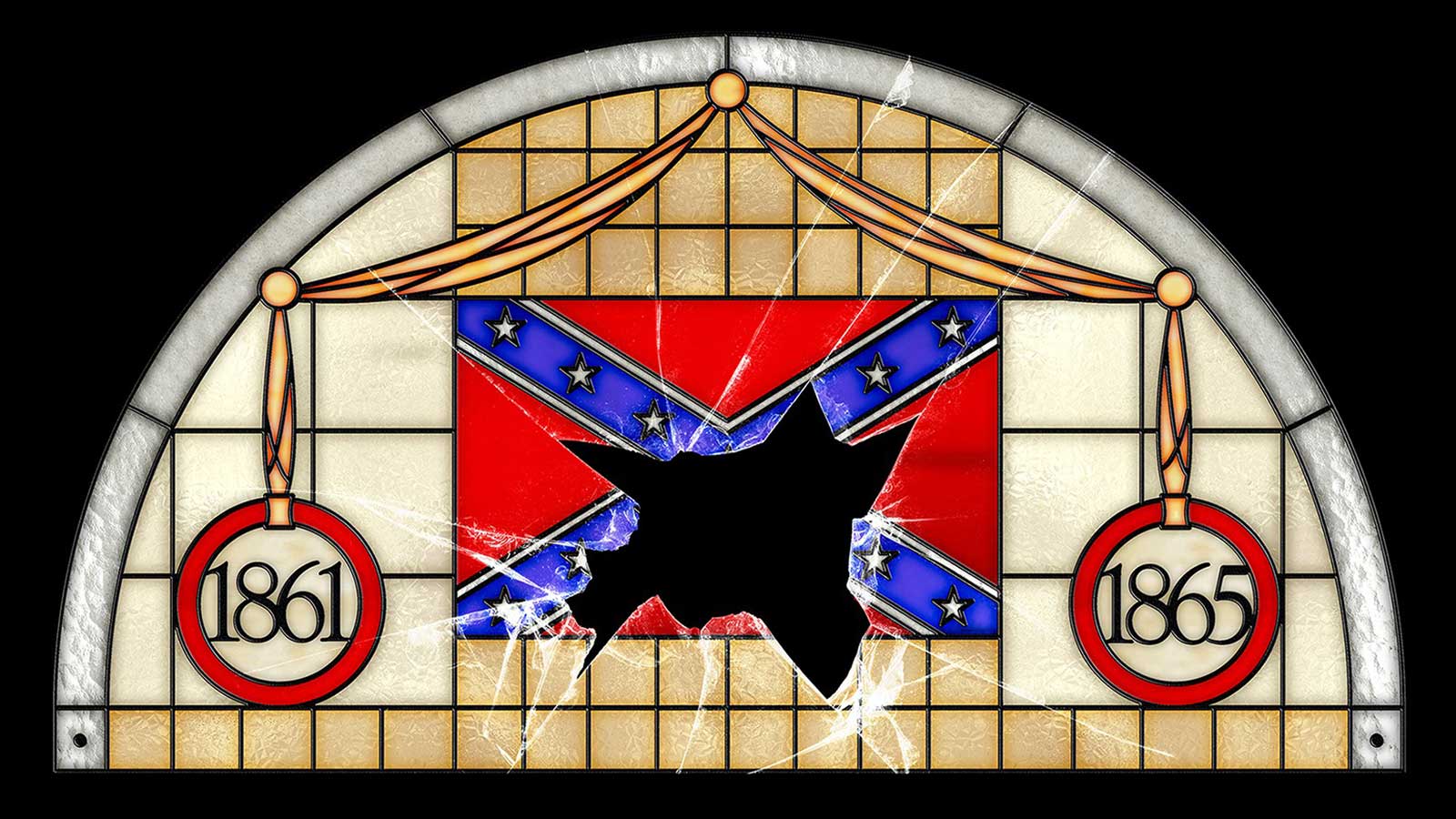

Most of the people who come to Blandford Cemetery, in Petersburg, Virginia, come for the windows—masterpieces of Tiffany glass in the cemetery’s deconsecrated church. One morning before the pandemic, I took a tour of the church along with two other visitors and our tour guide, Ken. When my eyes adjusted to the hazy darkness inside, I could see that in each window stood a saint, surrounded by dazzling bursts of blues and greens and violets. Below these explosions of color were words that I couldn’t quite make out. I stepped closer to one of the windows, and the language became clearer. Beneath the saint was an inscription honoring the men “who died for the Confederacy.”

Outside, lawn mowers buzzed as Black men steered them between tombstones draped in Confederate flags. The oldest marked grave at Blandford dates back to 1702; new funerals are held there every week. Within the cemetery’s 150 acres are the bodies of roughly 30,000 Confederate soldiers, one of the largest mass graves of Confederate servicemen in the country.

From 1866 into the 1880s, Ken told us, a group of local women organized the tracking-down and exhuming of those bodies from nearby battlegrounds. “They felt that the southern soldier had not been treated with the same dignity and honor that the northern soldiers had,” and they wanted to do something about it. Most of the bodies were not identifiable; sometimes all that was left was a leg or an arm. Nonetheless, the remains were dug up and brought here, and the ladies refurbished the old church as a memorial to their fallen husbands, sons, and brothers.

Tiffany Studios cut them a deal on the stained glass: $350 apiece instead of the usual price of about $1,700 ($51,000 today). Thirteen southern states donated funds. Ken outlined the aesthetic history of each window in meticulous detail, giving each color and engraving his thorough and intimate attention. But he said almost nothing about why the windows were there—that the soldiers memorialized in stained glass had fought a war to keep my ancestors in chains.

Almost all of the people who come to Blandford Cemetery are white. “It’s not that a Black population doesn’t appreciate the windows,” Ken, who is white, told me. “But sometimes in the context of what it represents, they’re not as comfortable.” He went on: “In most cases we try and fall back on the beauty of the windows, the Tiffany-glass kind of thing.”

But I couldn’t revel in the windows’ beauty without reckoning with what those windows represented. I looked around the church again. How many of the visitors to the cemetery today, I asked Ken, are Confederate sympathizers?

Confederate history is family history,

history as eulogy, in which loyalty takes precedence over truth.

“I think there’s a Confederate empathy,” he replied. “People will tell you, ‘My great-great-grandmother, my great-great-grandfather are buried out here.’ So they’ve got long southern roots.”

We left the church, and a breeze slid across my face. Many people go to places like Blandford to see a piece of history, but history is not what is reflected in that glass. A few years ago, I decided to travel around America visiting sites that are grappling—or refusing to grapple—with America’s history of slavery. I went to plantations, prisons, cemeteries, museums, memorials, houses, and historical landmarks. As I traveled, I was moved by the people who have committed their lives to telling the story of slavery in all its fullness and humanity. And I was struck by the many people I met who believe a version of history that rests on well-documented falsehoods.

For so many of them, history isn’t the story of what actually happened; it is just the story they want to believe. It is not a public story we all share, but an intimate one, passed down like an heirloom, that shapes their sense of who they are. Confederate history is family history, history as eulogy, in which loyalty takes precedence over truth. This is especially true at Blandford, where the ancestors aren’t just hovering in the background—they are literally buried underfoot.

We went over to the visitors’ center, where Ken introduced me to his boss, Martha, a kind-looking woman with tortoiseshell glasses.

She said her interest in women’s history had drawn her to Blandford. “This is how they helped to get through their grief,” she told me. “And this is what their result was, this beautiful chapel.” She added, “I think you could take the Civil War aspect totally out of it and enjoy the beauty.”

I asked her whether Blandford was concerned that, by presenting itself in such a positive light, it might be distorting its connection to a racist and treasonous cause.

She told me that a lot of people ask why the war was fought. “I say, ‘Well, you get five different historians who have written five different books; I’m going to have five different answers.’ It’s a lot of stuff. But I think from the perspective of my ancestors, it was not slavery. My ancestors were not slaveholders. But my great-great-grandfather fought. He had federal troops coming into Norfolk. He said, ‘Nuh-uh, I’ve got to join the army and defend my home state.’ ”

As we spoke, I looked down at the counter and reached for one of the flyers stacked there. Martha’s gaze followed my hand. Her face turned red and she thrust her hand down to flip the paper over, attempting to cover the rest of the leaflets. “Don’t even look at this. I’m sorry,” she said. “I will tell you, from a personal standpoint, I’m kind of bothered.”

I looked at the flyer again, trying to read between her fingers. It was a handout for a Memorial Day event at Blandford hosted by the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Paul C. Gramling Jr., then the commander in chief of the group, would be speaking. It was May 2019, and the event was just a few weeks away.

“I don’t mind that they come on Memorial Day and put Confederate flags on Confederate graves. That’s okay,” she said. “But as far as I’m concerned, you don’t need a Confederate flag on—” She stumbled over a series of sentences I couldn’t follow. Then she collected herself and took a deep breath. “If you’re just talking about history, it’s great, but these folks are like, ‘The South shall rise again.’ It’s very bothersome.”

She told me that she’d attended a Sons of Confederate Veterans event once but wouldn’t again. “These folks can’t let things go. I mean, it’s not like they want people enslaved again, but they can’t get over the fact that history is history.”

More people were coming into the visitors’ center, and I didn’t want to keep Ken and Martha from their work. We shook hands, and I made my way out the door. Before getting back in my car, I walked across the street, to another burial ground, this one much smaller. The People’s Memorial Cemetery was founded in 1840 by 28 members of Petersburg’s free Black community. Buried on this land are people who were enslaved; a prominent antislavery writer; Black veterans of the Civil War, World War I, and World War II; and hundreds of other Black residents.

There are far fewer tombstones than at Blandford. There are no flags on the graves. And there are no hourly tours for people to remember the dead. There is history, but also silence.

After my visit to Blandford, I kept thinking about the way Martha had flipped over the Memorial Day flyer, the way her face had turned red. If she hadn’t responded like that, I don’t know that I would have felt so curious about what she was trying to hide. But my interest had been piqued. I wanted to find out what Martha was so ashamed of.

Founded in 1896, the Sons of Confederate Veterans describes itself as an organization of about 30,000 that aims to preserve “the history and legacy of these heroes, so future generations can understand the motives that animated the Southern Cause.” It is the oldest hereditary organization for men who are descendants of Confederate soldiers. I was wary of going to the celebration alone, so I asked my friend William, who is white, to come with me.

The entrance to the cemetery was marked by a large stone archway with the words our confederate heroes on it. Maybe a couple hundred people were sitting in folding chairs around a large white gazebo. Children played tag among the trees; people hugged and slapped one another on the back. I felt like I was walking in on someone else’s family reunion. Dixie flags bloomed from the soil like milkweeds. There were baseball caps emblazoned with the Confederate battle flag, biker vests ornamented with the seals of seceding states, and lawn chairs bearing the letters UDC, for the United Daughters of the Confederacy. In front of the gazebo were two flags, one Confederate, one American, standing side by side, as if 700,000 people hadn’t been killed in the epic conflagration between them.

More than a few people turned around in their seat and looked with puzzlement, and likely suspicion, at the Black man they had never seen before standing in the back of a Sons of Confederate Veterans crowd.

William and I stood in the back and watched. The event began with an honor guard—a dozen men dressed in Confederate regalia, carrying rifles with long bayonets. Their uniforms were the color of smoke; their caps looked as if they had been bathed in ash. Everyone in the crowd stood up as they marched by. The crowd recited the Pledge of Allegiance, then sang “The Star-Spangled Banner.” After a pause came “Dixie,” the unofficial Confederate anthem. The crowd sang along with a boisterous passion: “Oh, I wish I was in the land of cotton / Old times there are not forgotten / Look away! Look away! Look away! Dixie Land.”

I glanced around as everyone sang in tribute to a fallen ancestral home. A home never meant for me. Speakers came to the podium, each praising the soldiers buried under our feet. “While those who hate seek to remove the memory of these heroes,” one said, “these men paid the ultimate price for freedom, and they deserve to be remembered.”

More than a few people turned around in their seat and looked with puzzlement, and likely suspicion, at the Black man they had never seen before standing in the back of a Sons of Confederate Veterans crowd. A man to my right took out his phone and began recording me. The stares began to crawl over my skin. I had been taking notes; now I slowly closed my notebook and stuck it under my arm, doing my best to act unfazed. Without moving my head, I scanned the crowd again. The man in front of me had a gun in a holster.

A man in a tan suit and a straw boater approached the podium. His dark-blond hair fell to his shoulders, and a thick mustache and goatee covered his lips. I recognized him as Paul C. Gramling Jr. from the flyer. He began by sharing a story about the origins of Memorial Day. “I don’t know if it’s true or not, but I like it,” he said, before reading aloud the account of a ceremony that took place on April 25, 1866, in Columbus, Mississippi, when a group of women “decorated the graves of both Union and Confederate soldiers.” Those soldiers, he continued, had “earned their rightful place to be included as American veterans. We should embrace our heritage as Americans, North and South, Black and white, rich and poor. Our American heritage is the one thing we have in common.”

Gramling’s speech was strikingly similar to those at Memorial Day celebrations after the end of Reconstruction, when orators stressed reconciliation, paying tribute to the sacrifices on both sides of the Civil War without accounting for what the war had actually been fought over.

Gramling then turned his attention to the present-day controversy about Confederate monuments—to the people who are “trying to take away our symbols.” In 2019, according to a report from the Southern Poverty Law Center, there were nearly 2,000 Confederate monuments, place names, and other symbols in public spaces across the country. A follow-up report after last summer’s racial-justice protests found that more than 160 of those symbols had been removed or renamed in 2020.

Gramling said that this was the work of “the American ISIS.” He looked delighted as the crowd murmured its affirmation. “They are nothing better than ISIS in the Middle East. They are trying to destroy history they don’t like.”

I thought about friends of mine who have spent years fighting to have Confederate monuments removed. Many of them are teachers committed to showing their students that we don’t have to accept the status quo. Others are parents who don’t want their kids to grow up in a world where enslavers loom on pedestals. And many are veterans of the civil-rights movement who laid their bodies on the line, fighting against what these statues represented. None of them, I thought as I looked at the smile on Gramling’s face, is a terrorist.

Gramling urged all who were present to understand the true meaning of the Confederacy and to “take back the narrative.” When his speech ended, two men in front of William and me started swinging large Confederate flags with unsettling fervor. Another speech was given. Another song was sung. Wreaths were laid. The honor guard then lifted its rifles and fired into the sky three times. The first shot took me by surprise, and my knees buckled. I shut my eyes for the second shot, and again for the third. I felt a tightening of muscles inside my mouth, muscles I hadn’t known were there.

“I don’t know if it’s true or not, but I like it”—I kept coming back to Gramling’s words. That comment was revealing. Many places in the South claim to be the originator of Memorial Day, and the story is at least as much a matter of interpretation as of fact. According to the historian David Blight, the first Memorial Day ceremony was held in Charleston, South Carolina, in May 1865, when Black workmen, most of them formerly enslaved, buried and commemorated fallen Union soldiers.

Confederates had converted Charleston’s Washington Race Course and Jockey Club into an outdoor prison for captured Union soldiers. The conditions were so terrible that nearly 260 men died and were buried in a mass grave behind the grandstand. After the Confederates retreated, Black men reburied the dead in proper graves and erected an archway bearing the words martyrs of the race course. An enormous parade was held on the track, with 3,000 Black children singing “John Brown’s Body,” the Union marching song. The first Memorial Day, as Blight describes it, received significant press coverage. But it faded from public consciousness after the defeat of Reconstruction.

It was then, in the late 1800s, that the myth of the Lost Cause began to take hold. The myth was an attempt to recast the Confederacy as something predicated on family and heritage rather than what it was: a traitorous effort to extend the bondage of millions of Black people. The myth asserts that the Civil War was fought by honorable men protecting their communities, and not about slavery at all.

We know this is a lie, because the people who fought in the Civil War told us so. “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world,” Mississippi lawmakers declared during their 1861 secession convention. Slavery was “the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution,” the Confederate vice president, Alexander Stephens, said, adding that the Confederacy was founded on “the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man.”

The Lost Cause asks us to ignore this evidence. Besides, it argues, slavery wasn’t even that bad.

“I don’t know if it’s true or not, but I like it”—I kept coming back to those words.

The early 1900s saw a boom in Confederate-monument building. The monuments were meant to reinforce white supremacy in an era when Black communities were being terrorized and Black social and political mobility impeded. They were also intended to teach new generations of white southerners that the cause their ancestors had fought for was just.

That myth tried to rewrite U.S. history, and my visit to Blandford showed how, in so many ways, it had succeeded.

After the speeches, I began talking with a man named Jeff, who had a long salt-and-pepper ponytail and wore a denim vest adorned with Confederate badges. He told me that several of his ancestors had fought for the Confederacy. I asked what he thought of the event. “Well,” he said, “I think if anyone never knew the truth, they heard it today.”

He spoke about the importance of the Confederate flag and monuments, contending that they were essential pieces of history. “They need to be there for generations in the future, because they need to know the truth. They can’t learn the truth if you do away with history. You’ll never learn. And once you do away with that type of thing, you become a slave.”

I was startled by his choice of words but couldn’t tell whether it was intentionally provocative or rhetorical coincidence.

“I think everybody should learn the truth,” Jeff said, wiping the sweat from his forehead.

“What is that truth?” I asked.

“Everybody always hears the same things: ‘It’s all about slavery.’ And it wasn’t,” he said. “It was about the fact that each state had the right to govern itself.”

He pointed to a tombstone about 20 yards away, telling me it belonged to a “Black gentleman” named Richard Poplar. Jeff said Poplar was a Confederate officer who was captured by the Union and told he would be freed if he admitted that he’d been forced to fight for the South. But he refused.

Poplar, I would learn, is central to the story many people in Petersburg tell about the war. The commemoration of Poplar seems to have begun in 2003, when the local chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans pushed for an annual “Richard Poplar Day.” In 2004, the mayor signed a proclamation establishing the holiday; she called Poplar a “veteran” of the Confederate Army. The tombstone with his name on it was erected at Blandford.

But the reality is that Black men couldn’t serve in the Confederate Army. And an 1886 obituary suggests that Poplar was a cook for the soldiers, not someone engaged in combat.

Some people say that up to 100,000 Black soldiers fought for the Confederate Army, in racially integrated regiments. No evidence supports these claims, as the historian Kevin M. Levin has pointed out, but appropriating the stories of men like Poplar is a way to protect the Confederacy’s legacy. If Black soldiers fought for the South, how could the war have been about slavery? How could it be considered racist now to fly the Dixie flag?

One Confederate general, Patrick Cleburne, actually did float the idea of using enslaved people as soldiers, but he was scoffed at. A senator from Virginia is reported to have asked, “What did we go to war for, if not to protect our property?” General Howell Cobb was even more explicit: “If slaves will make good soldiers, our whole theory of slavery is wrong.” In a desperate move just weeks before General Robert E. Lee’s surrender, the Confederacy approved legislation that would allow Black people to be used in battle. But by then it was too late.

I asked Jeff whether he thought slavery had played a role in the start of the Civil War. “Oh, just a very small part. I mean, we can’t deny it was there. We know slave blocks existed.” But only a small number of plantations even had slaves, he said.

It was a remarkable contortion of history, reflecting a century of Lost Cause propaganda.

Two children ran behind me, chasing a ball. Jeff smiled. He told me that he doesn’t call it the “Civil War,” because that distorts the truth. “We call it the ‘War Between the States’ or ‘of Northern Aggression’ against us,” he said. “Southern people don’t call it the Civil War, because they know it was an invasion … If you stayed up north, ain’t nothing would’ve happened.”

When Jeff said “nothing would’ve happened,” I wondered if he had forgotten the millions of Black people who would have remained enslaved, those for whom the status quo would have meant ongoing bondage. Or did he remember but not care?

A mosquito buzzed by Jeff’s ear, and he swatted it away. He told me that 78 of his family members were buried in the cemetery, dating back to 1802, and he had been coming here since he was 4 years old.

“Some nights I just sit there and just watch the deer come out,” he said, pointing to the gazebo, his voice becoming soft. “I just enjoy the feeling. I reminisce … I want to preserve history and save what I can for my granddaughters.

“This is a place of peace,” he said. “The dead don’t bother me. It’s the living that bother me.”

Alittle later, I was speaking with a mother and son about how often they came to events like these when a man in a Confederate uniform, carrying a saber in his left hand, approached us and stood a few feet away. I watched him from the corner of my eye, unsure whether he was trying to intimidate me or join the conversation.

I turned toward him, introducing myself and getting his name: Jason. He had a thick black beard and a mop of hair underneath his gray cap. He told me that “Civil War reenactor” had sounded like a cool job. “I didn’t realize it’s all volunteer,” he said with a laugh.

I asked him what he believed the cause of the Civil War had been. “How do I put this gently?” he said. “People are not as educated as they should be.” They’re taught that “these men were fighting to keep slavery legal, and if that’s what you grow up believing, you’re looking at people like me wearing this uniform: ‘Oh, he’s a racist.’ ” He said he’d done a lot of research and decided the war was much more complicated.

“We used to be able to stand on the monuments on Monument Avenue [in Richmond, Virginia]—those Lee and Jackson monuments. We can’t do it anymore, ’cause it ain’t safe. Someone’s gonna drive by and shoot me. You know, that’s what I’m afraid of.”

I thought that scenario was unlikely; cities have spent millions of dollars on police protection for white nationalists and neo-Nazis, people far more extreme than the Sons of Confederate Veterans. I found it a little ironic that these monuments had been erected in part to instill fear in Black communities, and now Jason was the one who felt scared.

The typical Confederate soldier hadn’t been fighting for slavery, he argued. “The average age was 17 to 22 for a Civil War soldier. Many of them had never even seen a Black man. The rich were the ones who had slaves. They didn’t have to fight. They were draft-exempt. So these men are going to be out here and they’re going to be laying down their lives and fighting and going through the hell of camp life—the lice, the rats, and everything else—just so this rich dude in Richmond, Virginia, or Atlanta, Georgia, or Memphis, Tennessee, can have some slaves? That doesn’t make sense … No man would do that.”

But the historian Joseph T. Glatthaar has challenged that argument. He analyzed the makeup of the unit that would become Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and pointed out that “the vast majority of the volunteers of 1861 had a direct connection to slavery.” Almost half either owned enslaved people or lived with a head of household who did, and many more worked for slaveholders, rented land from them, or had business relationships with them.

Many white southerners who did not own enslaved people were deeply committed to preserving the institution. The historian James Oliver Horton wrote about how the press inundated white southerners with warnings that, without slavery, they would be forced to live, work, and inevitably procreate with their free Black neighbors.

The Louisville Daily Courier, for example, warned nonslaveholding white southerners about the slippery slope of abolition: “Do they wish to send their children to schools in which the negro children of the vicinity are taught? Do they wish to give the negro the right to appear in the witness box to testify against them?” The paper threatened that Black men would sleep with white women and “amalgamate together the two races in violation of God’s will.”

These messages worked, Horton’s research found. One southern prisoner of war told a Union soldier standing watch, “You Yanks want us to marry our daughters to niggers”; a Confederate artilleryman from Louisiana said that his army had to fight against even the most difficult odds, because he would “never want to see the day when a negro is put on an equality with a white person.”

The proposition of equality with Black people was one that millions of southern white people were unwilling to accept. The existence of slavery meant that, no matter your socioeconomic status, there were always millions of people beneath you. As the historian Charles Dew put it, “You don’t have to be actively involved in the system to derive at least the psychological benefits of the system.”

Jason and I were finishing our conversation when another man, with a thick gray beard and a balding head, walked up to us. We shook hands as he and Jason greeted each other warmly. “He’s a treasure trove of information,” Jason said. I mentioned that I had seen him talking with my friend William. “I been in his ear good,” the man said, telling me that he’d even given him his phone number. I said that was very generous. He looked at me, his eyes searching. His face shifted. “I told him, if you write about my ancestors”—the air trembled between us—“I want it to be correct. I’m concerned about the truth, not mythology.”

Like blandford cemetery, the Whitney Plantation in Louisiana has a church. It is large and white and flaked with a thin coat of dirt. The door whistles as it opens, and the wooden floor moans under your feet as you step inside. There are no stained-glass windows here.

Instead, scattered throughout the church’s interior—standing next to the pews, sitting on the floor, hiding in the corners—are statues. There are more than two dozen of them, life-size sculptures of children with eyes like small, empty planets. The boys wear shorts or overalls; the girls, simple dresses. When I saw them I was startled because, at first glance, I thought they were real. Each one was so alive despite its inanimateness, intricately detailed from the contours of the lips to the bridge of the nose. They look like they’re listening, or waiting. They are The Children of Whitney, designed for the plantation by the artist Woodrow Nash.

Once one of the most successful sugarcane enterprises in all of Louisiana, the Whitney is surrounded by a constellation of former plantations that host lavish events—bridal parties dancing the night away on land where people were tortured, taking selfies in front of the homes where enslavers lived. Visitors bask in nostalgia, enjoying the antiques and the scenery. But the Whitney is different. It is the only plantation museum in Louisiana with an exclusive focus on enslaved people. The old plantation house still stands—alluring in its decadence—but it’s not there to be admired. The house is a reminder of what slavery built, and the grounds are a reminder of what slavery really meant for the men, women, and children held in its grip.

On a plot of earth tucked into a corner of the property, between a white wooden fence and a redbrick path, are the dark heads of 55 Black men, impaled on silver stakes. Their eyes are shut, their faces peaceful or anguished. They’re ceramic, but so lifelike that the gleam of the sun could as easily be the sheen of blood and sweat. These heads represent the rebels in the largest slave revolt in American history, which took place not far from here in 1811. Within 48 hours, local militia and federal troops had suppressed the uprising. Many rebels were slaughtered, their heads cut off and posted on stakes lining the Mississippi River.

Like Blandford, the Whitney also has a cemetery, of a kind. A small courtyard called the Field of Angels memorializes the 2,200 enslaved children who died in St. John the Baptist Parish from 1823 to 1863. Their names are carved into granite slabs that encircle the space. My tour guide, Yvonne, the site’s director of operations, explained that most had died of malnutrition or disease. Yvonne, who is Black, added that there were stories of some enslaved mothers killing their own babies, rather than sentencing them to a life of slavery.

At the center of the courtyard is a statue of an angel down on one knee. Her chest is bare and a pair of wings juts from her back. Her hair is pulled into thick rows of braids and her head is bent, eyes cast downward at the limp body of the small child in her hands.

My own son was almost 2 at the time, and his baby sister was a couple of weeks from making her way into the world. This child, cradled in the angel’s hands, evoked in me a surge of grief I had not expected. I felt the blood leave my fingers. I had to push out of my head the image of my own child in those hands. I had to remind myself to breathe.

“There’s so many misconceptions about slavery,” Yvonne said. “People don’t really consider the children who were brought over, and the children who were born into this system, and the way to get people to let their guard down when they come here is being confronted with the reality of slavery—and the reality of slavery is child enslavement.”

Before the coronavirus pandemic, the Whitney was getting more than 100,000 visitors a year. I asked Yvonne if they were different from the people who might typically visit a plantation. She looked down at the names of the dead inscribed in stone. “No one is coming to the Whitney thinking they’re only coming to admire the architecture,” she said.

Did the white visitors, I asked her, experience the space differently from the Black visitors? She told me that the most common question she gets from white visitors is “I know slavery was bad … I don’t mean it this way, but … Were there any good slave owners?”

She took a deep breath, her frustration visible. She had the look of someone professionally committed to patience but personally exhausted by the toll it takes.

“I really give a short but nuanced answer to that,” she said. “Regardless of how these individuals fed the people that they owned, regardless of how they clothed them, regardless of if they never laid a hand on them, they were still sanctioning the system … You can’t say, ‘Hey, this person kidnapped your child, but they fed them well. They were a good person.’ How absurd does that sound?”

But so many Americans simply don’t want to hear this, and if they do hear it, they refuse to accept it. After the 2015 massacre of Black churchgoers in Charleston led to renewed questions about the memory and iconography of the Confederacy, Greg Stewart, another member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, told The New York Times, “You’re asking me to agree that my great-grandparent and great-great-grandparents were monsters.”

So much of the story we tell about history is really the story we tell about ourselves. It is the story of our mothers and fathers and their mothers and fathers, as far back as our lineages will take us. They are the stories Jeff tells as he sits watching the deer scamper among the Blandford tombstones at dusk. The stories he wants to tell his granddaughters when he holds their hands as they walk over the land. But just because someone tells you a story doesn’t make that story true.

Would Jeff’s story change, I wonder, if he went to the Whitney? Would his sense of what slavery was, and what his ancestors fought for, survive his coming face-to-face with the Whitney’s murdered rebels and lost children? Would he still be proud?

Source: The Atlantic

Clint Smith is a staff writer at The Atlantic and the author of the poetry collection Counting Descent and the forthcoming nonfiction book How the Word Is Passed.

This article has been adapted from Clint Smith’s new book, How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning With the History of Slavery Across America. It appears in the June 2021 print edition with the headline “The War on Nostalgia.”

Featured Image: By Paul Spella