For over a century, the Virginia Theological Seminary used Black Americans for forced labor. Now it’s determined to make amends.

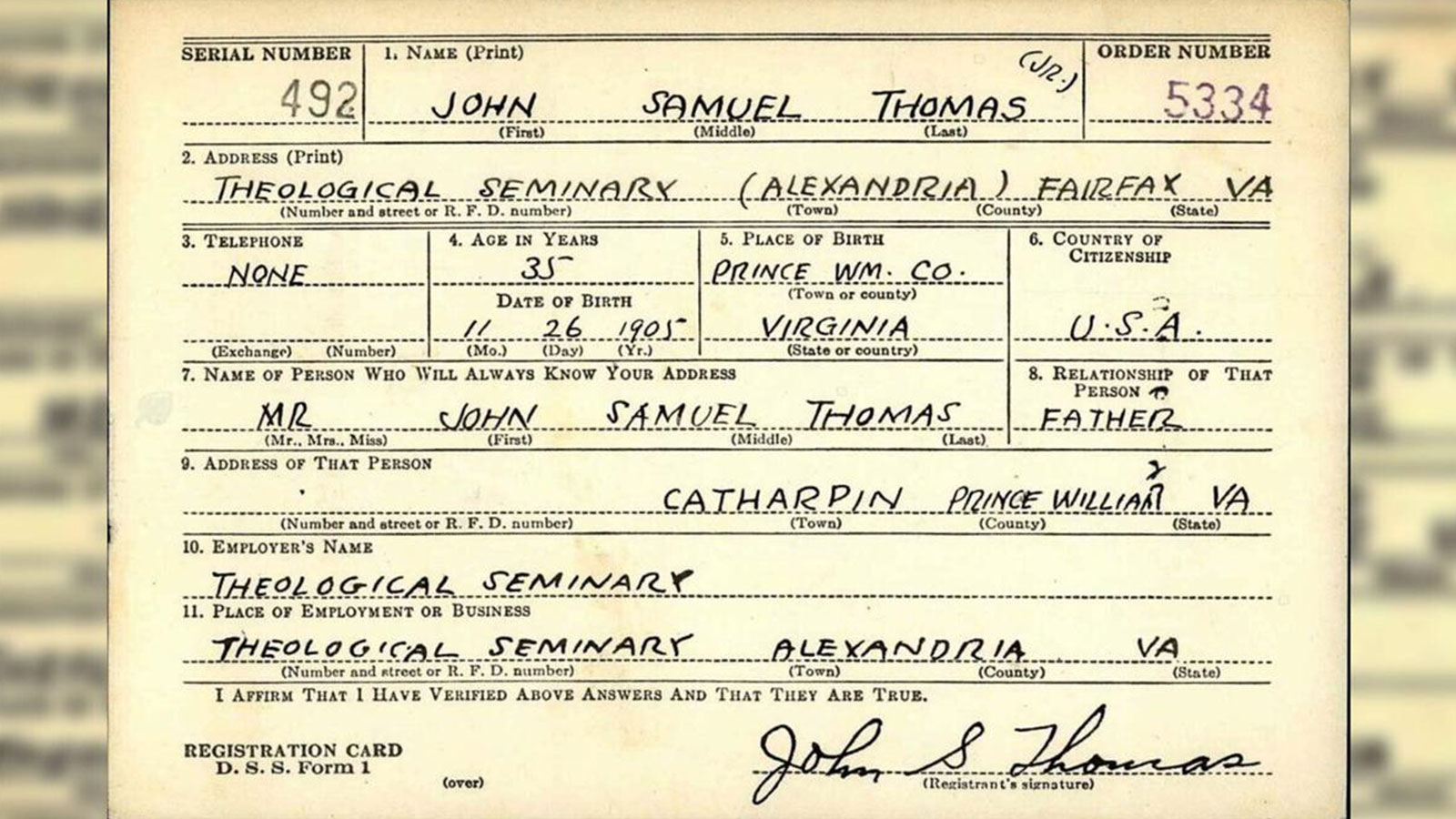

Linda Johnson-Thomas’ grandfather worked at the Virginia Theological Seminary for more than a decade, first as a farm laborer before moving up to head janitor.

Her grandparents lived in a little white house on campus with their four children, including her mother. But until two years ago, she had no idea that her grandfather, John Samuel Thomas Jr., had been forced to work at the school in Alexandria, just outside of Washington, D.C.

“All I knew was that he grew up on the seminary,” said Johnson-Thomas, 65, who lives in Mitchellville, Maryland. “We knew there were slaves in Alexandria — but we didn’t know the specifics.”

For more than a century — during slavery, Reconstruction and beyond — the seminary used Black Americans for forced labor. Between 1823 and 1951, hundreds of Black people were forced to work for little or no pay on the campus as farmers, dishwashers and cooks, among other jobs.

Back then faculty members and students also brought their own enslaved people, said Ebonee Davis, an associate for programming and historical research at the seminary.

In 2019 the school announced it had set aside $1.7 million to pay reparations to the descendants of slaves who worked on its campus. Earlier this year it made good on its promise and began handing out annual payments of $2,100 each to direct descendants of those who worked there.

Johnson-Thomas and her two sisters were the first recipients. Fifteen people have received payments so far, and the seminary is expecting to compensate many more as they are identified.

The cash payments began as conversations about reparations have rippled around the country since George Floyd’s murder last year. Some cities have proposed reparations programs, while the House Judiciary Committee in April passed a bill which would create a commission to study reparations for descendants of enslaved Americans and recommend remedies.

Some scholars of reparations say the seminary’s is the first such program in the country. But despite the promise of annual cash payouts, its recipients were wary at first.

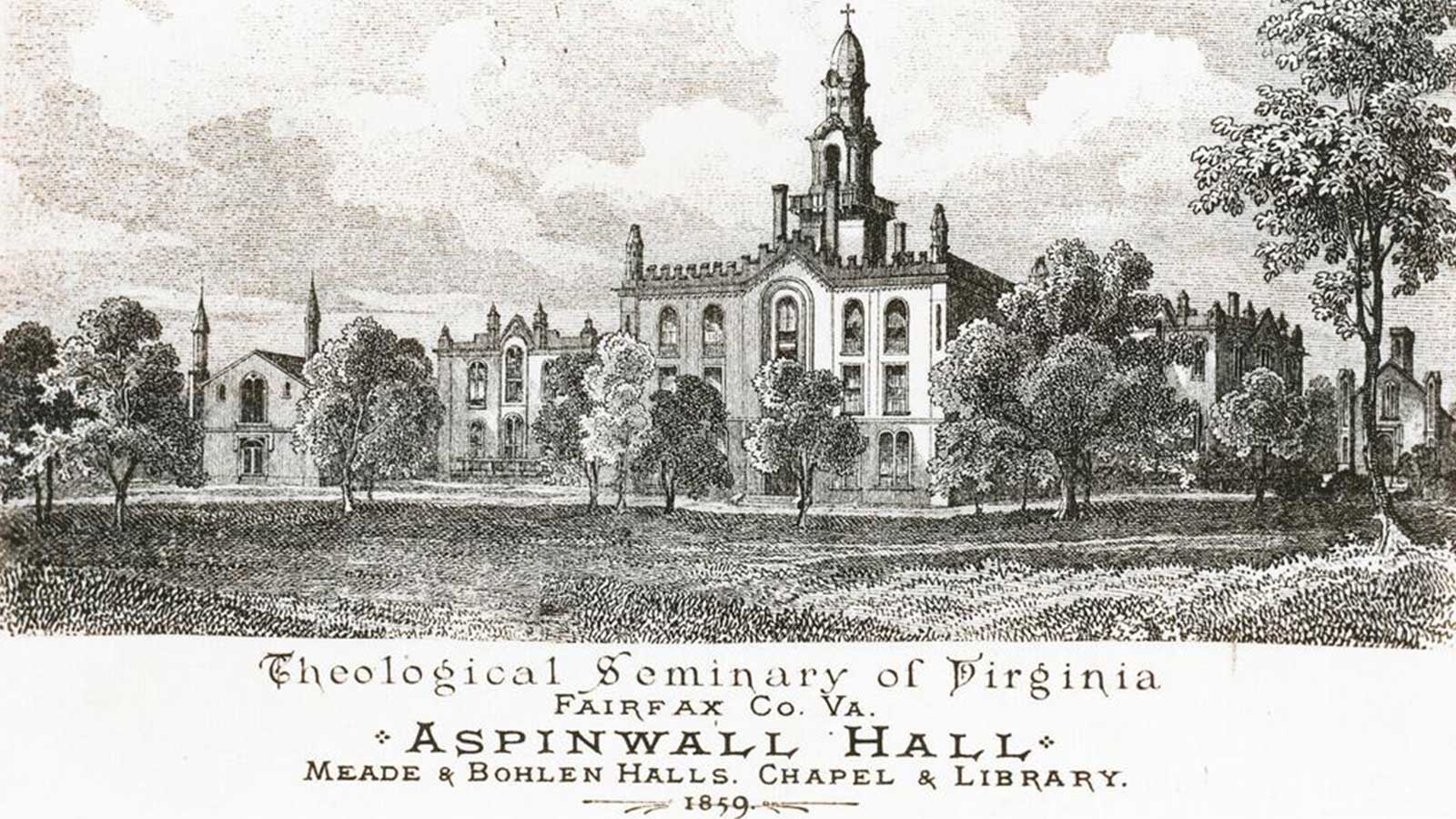

The seminary was founded in 1823 and has educated many leaders of the Episcopal Church.

The seminary has genealogists tracking down workers’ descendants

Since it announced the reparations endowment fund in September 2019, the seminary has begun the Herculean task of tracking down direct descendants of its enslaved workers.

It set up a task force. Genealogists pore over old documents to find relatives in far-flung parts of the nation. And when they do, another group takes over the process of reaching out to the direct descendants. The conversations can be difficult.

The money is given to the family generation that is closest to the enslaved person or Jim Crow-era laborer — often the grandchildren or great-grandchildren.

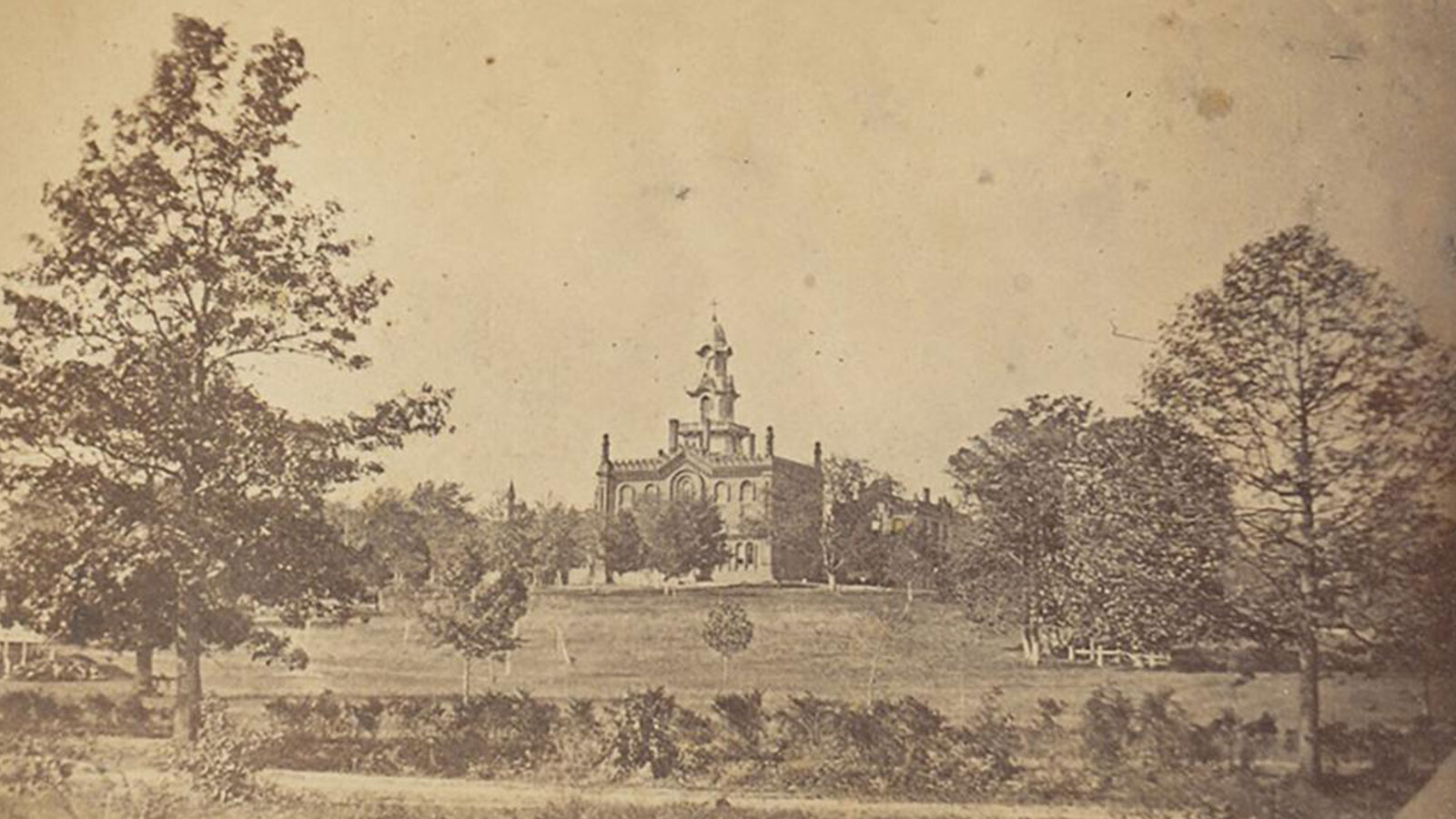

One of the oldest known photos of the seminary taken in 1863, during the Civil War.

The seminary started cutting checks for the descendants — whom it describes as shareholders — in February. The $1.7 million endowment is expected to grow and continue to fund future payments.

“Though no amount of money could ever truly compensate for slavery, the commitment of these financial resources means that the institution’s attitude of repentance is being supported by actions of repentance,” said Rev. Ian S. Markham, dean and president of the seminary, in a statement.

“It opens up a moment for us to reflect long and hard on what it will take for our society and institutions to redress slavery and its consequences with integrity and credibility.”

The endowment acknowledges the seminary’s past participation in oppression, and comes as the school prepares to celebrate its bicentennial in 2023.

“As we seek to mark the seminary’s milestone of 200 years, we do so conscious that our past is a mixture of sin as well as grace,” Markham said. “This is the seminary recognizing that along with repentance for past sins, there is also a need for action.”

She hopes the reparations will help change the dialogue on race

Johnson-Thomas first heard about the reparations program two years ago. When she learned her grandfather was one of the school’s laborers, she was stunned.

“My first thought was disbelief, which is why I scheduled a meeting with the dean,” she said. Her sister accompanied her for the meeting with Markham, who explained why the seminary chose to issue reparations.

“His point was, we are equal people and we realize and we recognize the racism in our past. We know there is no amount of money that can rectify what transpired back then, but we want to do something toward healing,” Johnson-Thomas said.

This process has taught her a lot about her grandfather, she said. She found out that while he worked at the seminary, he wanted to be a minister, but he could not get admission there because he was Black. African Americans were not allowed to attend the seminary until 1951.

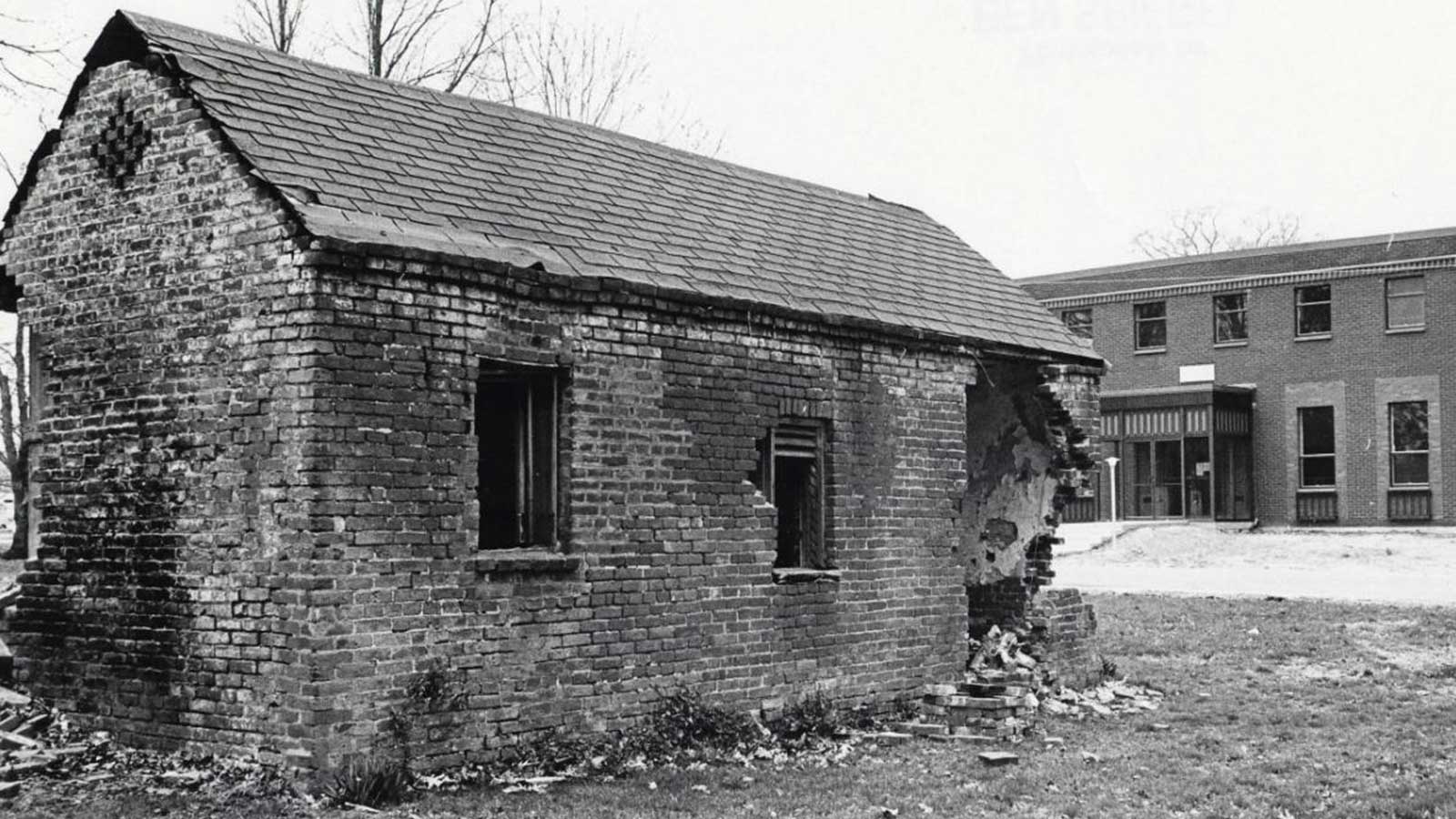

This servant quarters remained on the Virginia Theological Seminary campus into the 20th century. The building was dismantled in the 1970s and its bricks repurposed for a garage.

But that didn’t stop him from digging into the books at the seminary and driving his Ford Model T on his days off to preach at a nearby church. Before his death in 1967, her grandfather had fulfilled his goal and become a Baptist minister in Washington, D.C.

Johnson-Thomas followed in his footsteps and is a Baptist minister, too.

“While pursuing my master’s degree from Howard University in 2000, I studied in the library at VTS. I had no idea that it was the same campus that denied my grandfather the right to pursue an education,” she said.

While she said no amount of money can compensate for the sin of slavery, Johnson-Thomas hopes the reparations program will change the conversation on race and highlight how Black people have been historically exploited by institutions. Her grandfather worked at the seminary until the 1940s.

“Seventy years later, a wrong made right,” Johnson-Thomas said. “A quality education has been a struggle for African Americans in what many considered the land of the free. I’m hoping that it’s the beginning of more empowerment and diversity that will continue for generations.”

A draft card was one of the documents used to verify that John Samuel Thomas Jr. worked at the Virginia Theological Seminary.

He was skeptical at first but spent his birthday at the seminary

Gerald Wanzer has lived within five miles of the seminary for years.

In 2019, he got a call from the school seeking more information about his great-grandfather, who worked as a blacksmith there in the 1850s.

The seminary was founded in 1823, and Wallace Wanzer likely played a key role in some of its earliest metal works.

Wanzer said he was skeptical about the call at first. But five members of his family — a brother, a sister and a couple of nephews — each received a check from the seminary this year.

Wanzer said he hopes the program will help change the history of racism.

“They can never make up for past transgressions,” he said. “I just hope that people don’t take this as just a money giveaway and instead look at the whole issue of why this happened, why some of it is still happening. It’s been 150 years.”

Davis, the seminary’s associate, said the program goes beyond money reparations.

“With an understanding that no amount will ever be enough, we are allowing shareholders to be creative in their requests,” she said.

Some people are donating the money while others are submitting written wishes requesting it goes to others. The seminary is also allowing descendants to access the campus in ways their ancestors could not. That includes free use of amenities such as the cafeteria, coffee shop and computer lab, Davis said.

“So far the the community has received this quite well,” Davis said. “We had one family that was not interested in participating. They felt that it was too little, too late. But I let them know the door was always open.”

Wanzer has already taken them up on the offer. In March he spent his 77th birthday on the campus.

The seminary took him on a tour of the grounds and made him a special birthday meal of grilled chicken and baked halibut with potatoes and asparagus, he said. His children, grandchildren, nieces and nephews came, too.

Source: CNN